Articles & Features

The Shows That Made Contemporary Art History: The First Exhibition Of ‘Der Blaue Reiter’

“The whole body of work we call art knows neither borders nor nations but only humanity”.

Wassily Kandinsky

There are multiple ways to delve into the fascinating world of contemporary art. One may consider the development and succession of different artistic movements; the personalities of the major players in the field, from artists to theorists and curators; not to mention the most iconic artworks that have defined our era. But why not consider art exhibitions? It is an inescapable fact that the landmark exhibitions of the modern and contemporary period have impacted and shaped the course of art history almost as much as any other single determining factor, both launching entirely new genres and shaping the history and habits of exhibition-making through innovative practices. This week we feature the First exhibition of the editorial board of Der Blaue Reiter, held in Munich in 1911. Representative of a significant yet short-lived artistic group, the show embodied one of the most fascinating chapters in art history.

“This capacity of profound depth is found in blue. (…). The deeper the blue the more it beckons man into the infinite, arousing a longing for purity and the supersensuous. It is the colour of the heavens just as we imagine it, when we hear the word heaven. It attains an endless profound meaning sinking into the deep seriousness of all things where there is no end”.

Wassily Kandinsky

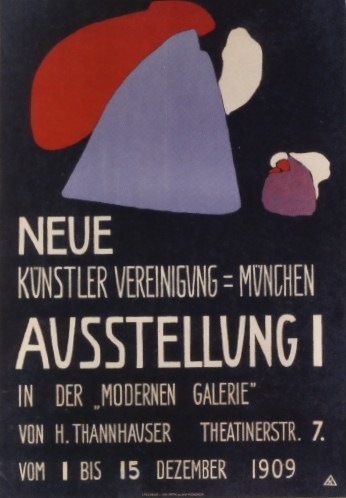

The background

To delve into the origin of what would become Der Blaue Reiter collective ( ‘The Blue Rider’), it is necessary to step back in time a couple of years. At the turn of the twentieth century, the Bavarian city of Munich was bustling with formidable artistic and cultural activity to the point of rivalling Paris as the international nexus for avant-garde art. In 1909, on the heels of Die Brücke (‘The Bridge’), a secessionist group of young artists working in Dresden, Russian artist Wassily Kandinsky – based in Munich at the time – founded the Neue Künstlervereinigung (NKV), the ‘New Artists’ Association’, for the purpose of creating an alternative to the mainstream art institutions and their exhibiting venues. The organisation gathered several German and Russian emigrant artists united by opposition to official academic art: besides Kandinsky, other members included his partner Gabriele Münter, Franz Marc, Alexey von Jawlensky, Adolf Erbslöh, Alexander Kanoldt, and Alfred Kubin. Even though they were all influenced by post-impressionist experiences, especially Fauvism, these artists shared the same free artistic approach rather than a specific painting style and aesthetic.

Their first exhibition turned out to be radical and provocative, too advanced for both the public and the critics of the time. To grasp the idea of how badly it was received, Heinrich Thannhauser, owner of the Moderne Galerie Thannhauser where the show was held, reported that he had to clean spit off the paintings each evening. However, as time passed, divergent views emerged within the Association and its principles progressively became more strict and conservative.

In December 1911, Kandinsky – no longer at the helm of NKV – submitted a painting for its third, upcoming exhibition; it was Composition V – later symbolically dubbed The Last Judgment. Predictably, the NKV jury strongly rejected his monumental piece on the verge of abstraction, causing dissension and scandal. It was the clarion call Kandinsky and others had been expecting: they were about to steal NKV show’s thunder.

The show

Following the heated debate concerning the rejection of Kandinsky’s piece, the Russian painter, along with Münter, Marc, and a few others, formed a rival group as a breakaway faction from the NKV and in no time organized a parallel show which resulted in even more provocation as it was held in the same venue, the Thannhauser Gallery, hanging in adjacent rooms to the official exhibition.

Years later, Kandinsky revealed how the situation had not taken him by surprise: “Our halls were close to the rooms of the NKVM exhibition. It was a sensation. Since I anticipated the ‘noise’ in good time, I had prepared a wealth of exhibition material for the BR [Blaue Reiter]. So the two exhibitions took place simultaneously. (…) Revenge was sweet!”.

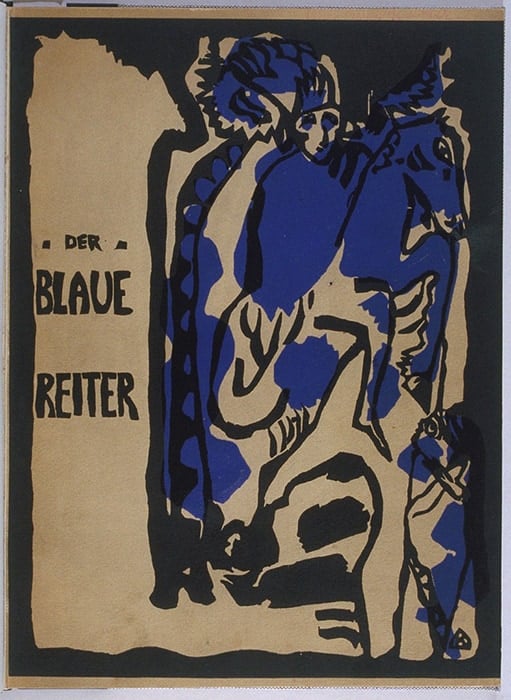

The two leading figures, Kandinsky and Marc, named the group ‘Der Blaue Reiter‘, and since for some time, they had been planning the publication of an Art Almanac the show took the name of ‘First exhibition of the editorial board of Der Blaue Reiter’.

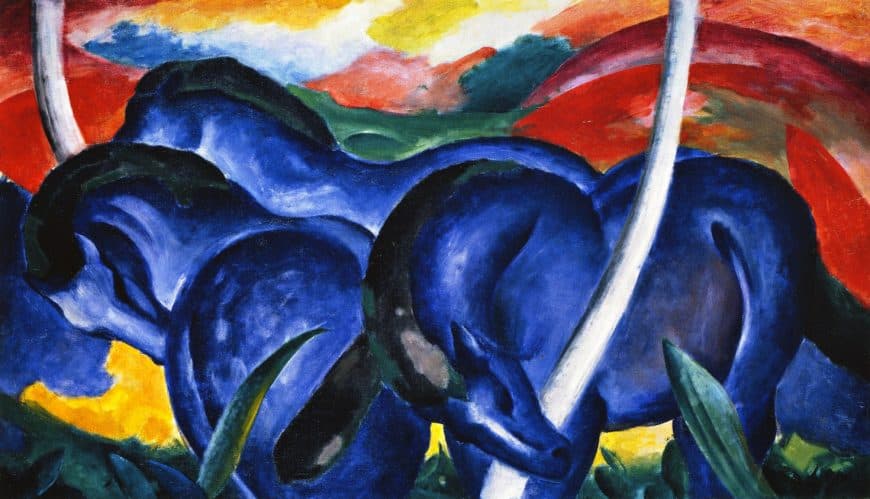

The reason why they chose ‘Der Blaue Reiter’ as a name is not entirely clear. For some time, it was believed that it referred to a Kandinsky painting from 1903, indeed titled The Blue Rider and depicting a horseman cloaked in blue galloping through the meadow, a pivotal work in the artist’s transition towards abstraction. However, the painter – though somewhat ironically – gave a less intellectual explanation: “We came up with the name ‘The Blue Rider’ whilst sitting drinking coffee together in the summer house, in Sindelsdorf. Both of us love the colour blue, Marc – horses, I – riders. So the name invented itself”.

Der Blaue Reiter was a network of like-minded artists rather than a coherent group. They banded together willing to represent something beyond reality, pursuing the spiritual dimension of art as an antidote to the alienation of modern times. According to their vision, colours – once liberated from representation purposes – held symbolic and emotional values, with blue being the most mystical. This explains why the Blue Rider is often interpreted as emblematic of art as the means to transcend reality and guide society to spirituality.

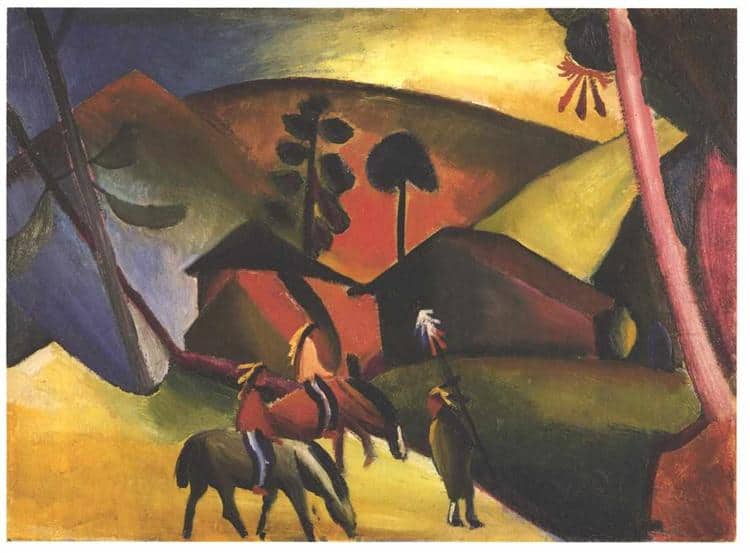

The legendary show displayed around fifty artworks of members of Der Blaue Reiter – in addition to the aforementioned, also August Macke, Alexej von Jawlensky, Marianne von Werefkin, Natalia Goncharova, and Paul Klee had joined the group – as well as works from other renowned artists such as Robert Delaunay and Henri Rousseau.

After Munich, for three years the show travelled across Europe, with venues in Cologne, Berlin, Bremen, Hagen, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Budapest, Oslo, Helsinki, Trondheim and Göteborg, becoming an international force in the promotion of the early Avant-garde.

“Only today can art be metaphysical, and it will continue to be so. Art will free itself from the needs and desires of men. We will no longer paint a forest or a horse as we please or as they seem to us, but as they really are”.

Franz Marc

Key concepts

Besides spirituality, Der Blaue Reiter artists were interested in the concept of synesthesia, the perceptual phenomenon in which the stimulation of one of the senses leads to involuntary experiences in another one. Particularly meaningful was the relationship between painting and music, colour and sound. Especially to Kandinsky, there was no difference between painting and composing: music could be seen, as well as painting could be heard. Not surprisingly, many of his paintings hold names typically attributed to musical pieces like ‘Composition’ or ‘Improvisation’.

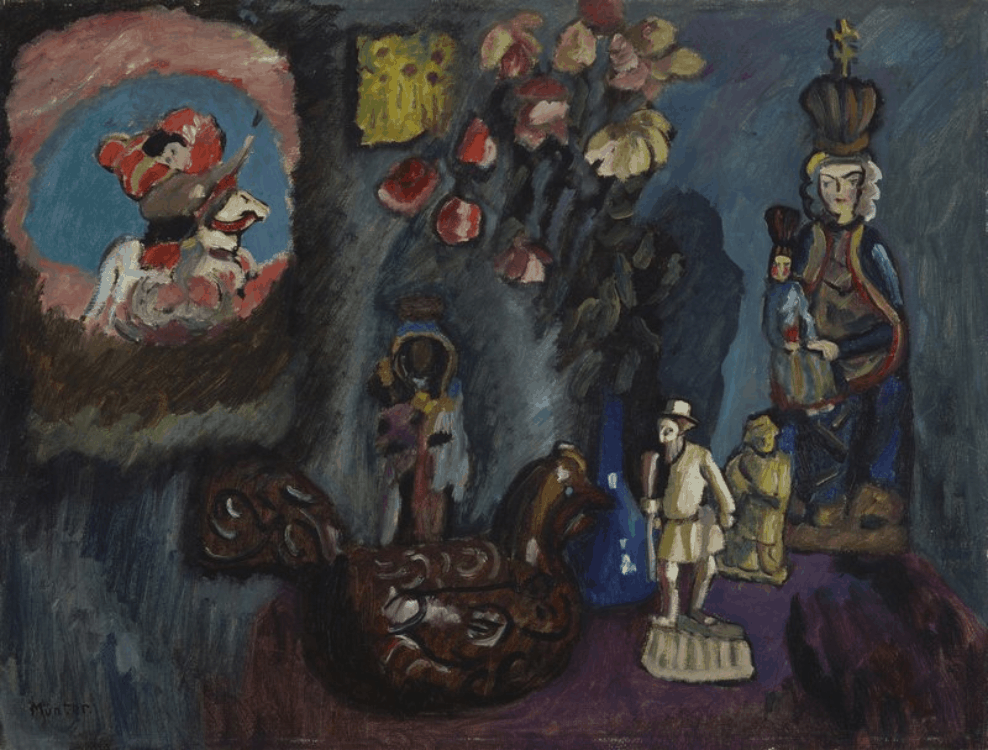

The group also shared the tendency that has come to be known as Primitivism, namely the fascination with all those forms of art not complying with the post-Renaissance Western creative canon, and therefore regarded as more authentic manifestations of spirituality – from folk and medieval art to tribal art from Africa, the South Pacific, and Indonesia; .

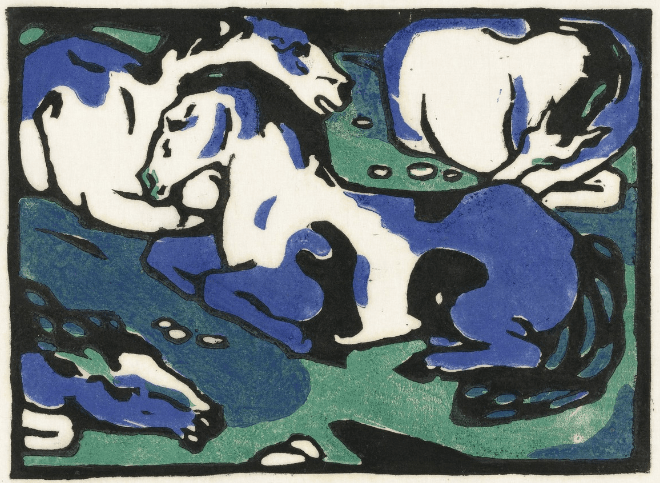

These features altogether, in addition to the intense and non-naturalistic use of colour as well as the free, textured brushwork, made Der Blaue Reiter one of the two faces of German Expressionism. While their counterpart, Die Brücke, used bold, dramatic colours to convey the profound sense of alienation and anxiety of modern urban life without ever abandoning figuration, the Munich collective found in the symbolism of colour and the tendency to abstraction the means to transcend reality.

Founded on this common ground, Der Blaue Reiter artists could express their unique personalities developing different styles and artistic languages. The principle of diversity was their strength, whilst their openness asserted their modernity.

Even though they lacked a manifesto in the narrow sense, their principles were summarised in Kandinsky’s treatise Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1910) but, above all, their philosophical approach was revealed in Der Blaue Reiter Almanach, edited by Kandinsky and Marc, and published in 1912.

As a defining statement and a “document of our modern art“, the almanac contained fourteen major articles and over a hundred reproductions of artworks by a range of artists from different cultures and periods. Turning away from a Eurocentric attitude, it included pieces by the Blaue Reiter members, works by Van Gogh, Cézanne, Picasso, Gauguin, and Henri Rousseau, but also Russian folk art, medieval German woodcuts and sculpture, Japanese drawings, pieces from the South Pacific, and Africa, drawings by children and musical compositions by Arnold Schönberg and Alban Berg in an unprecedented and unparalleled example of artistic interdisciplinarity.

The legacy of The First Exhibition Of ‘Der Blaue Reiter’

The collective set up only one other show at the ‘New Art’ Gallery of Hans Goltz in Munich. Less impactful than the previous one, it featured works on paper: watercolors, etchings, drawings, and woodcuts by both Der Blaue Reiter‘s members, Die Brücke artists, and other avant-garde figures such as Hans Arp, Georges Braque, André Derain, and Pablo Picasso.

In 1914, differences in opinion but mostly the tragic outbreak of the First World War brought disruption, and ultimately a conclusion to Der Blaue Reiter , also causing the end of a unique phase for Munich as a pioneering artistic centre. Many among the Russian artists, including Kandinsky, forcefully returned to their home country, others took refuge in Switzerland, while the Germans Franz Marc and August Macke died on the battlefield, their careers tragically cut short.

Except for a few enlightened minds, critical and public response to Der Blaue Reiter’s first show was not favourable at all, including the observation from Anton von Werner, director of the Berlin Art Academy, who described it as “an interesting object for a psychiatric study.” It was not until the aftermath of World War II that a significant retrospective exhibition held at the Munich House of Art in 1949 rehabilitated the Blaue Reiter project, finally acknowledging its remarkable value.

In fact, under the Nazi regime artworks by members of the Blaue Reiter were confiscated, sold abroad, or destroyed as examples of degenerate art. To avoid the increasing censorship measures, an incredible number of paintings ended up in garrets and basements, one of which belonged to Gabriele Münter, Kandisky’s partner until 1914, and a Blaue Reiter member herself. On the occasion of her 80th birthday in 1957, the artist endowed the Lenbachhaus in Munich with an extraordinary treasure she had kept hidden, a collection of more than a thousand works by the Blaue Reiter including ninety oil paintings by Kandinsky, hundreds of his watercolours, drawings, sketchbooks, prints, and reverse glass paintings, as well as pieces by Münter herself and other eminent artists of the group.

Despite its short existence, Der Blaue Reiter, with its groundbreaking 1911 show, proved to be extremely influential on movements and generations of artists to come. Not only did it represent one of the two sides of German Expressionism, but also it foreshadowed many aspects that would later define contemporary art. The development of Suprematism in Russia, the trailblazing experience of Bauhaus – where both Kandinsky and Klee taught lessons in the twenties – and, ultimately, the flourishing of abstract art would be all unthinkable without Der Blaue Reiter‘s essential contribution.

Relevant sources to learn more

Lenbachhaus, Munich

From Museum to Basement and Back: The Incredible History Of A Russian Avant-Garde Treasure

For previous editions of our “Shows That Made Contemporary Art History” series, see:

The Shows That Made Contemporary Art History: The Salon Des Refusés