Articles and Features

Controversial Public Art. Debate, Fury, Vandalism and Loss.

By: Tori Campbell

Controversial Public Art

When controversial art stands behind the closed doors of museums and galleries, it gains the attention of only its most outspoken critics. However, when the art is displayed in the public realm of civic or communal spaces, mingling in the everyday lives of people, occasionally paid for with the taxpayer’s dollar — the artworks can be subject to much more controversy and ire. The large-scale installations explored here are some of the most controversial public art pieces in history; some removed by court-order, many vandalised by sledgehammers or graffiti — and a few that still stand today, ready for a new batch of outrage and debate. Read on to see which side you stand with: that of the critics, or the artists?

Richard Serra: Tilted Arc

In 1979 the United States General Services Administration’s Art-in-Architecture program decided to commission a large-scale piece of public art for the plaza in front of a planned addition to the Jacob K. Javits Federal Building in New York City. Upon the advice of a panel of art experts, Richard Serra, a minimalist sculptor of considerable acclaim, was chosen. With an exemplary piece of post-minimalist work, Serra installed Tilted Arc in 1981, and it quickly became one of the most controversial public art pieces of all time. The solid unfinished plate of steel, spanning 120 feet in length and 12 feet in height, bisected the Federal Plaza, intentionally necessitating new paths for those who frequented the building as Serra explained “”The viewer becomes aware of himself and of his movement through the plaza. As he moves, the sculpture changes. Contraction and expansion of the sculpture result from the viewer’s movement. Step by step, the perception not only of the sculpture but of the entire environment changes.” The piece inspired immediate backlash due to its physical imposition on the government workers, and within mere months over 1300 employees had signed a petition for its removal. Arguing that the piece in its very nature was site specific, and having it relocated would destroy the work entirely, Serra had the support of influential members of the artistic community in a 1985 hearing about Tilted Arc’s removal — including Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, and Phillip Glass. Despite this support, a jury ultimately voted 4-1 to have the sculpture removed; and due to Serra’s insistence that the work never be exhibited again, it remains in government storage to this day.

Courtesy Richard Serra

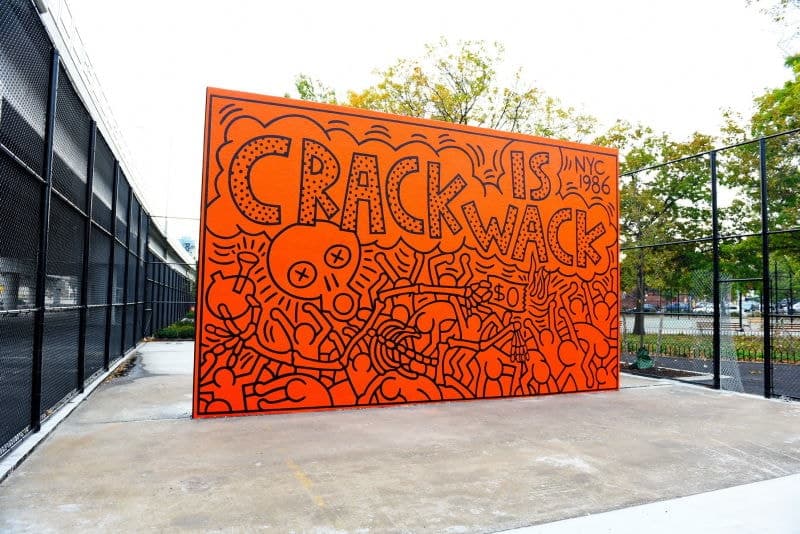

Keith Haring: Crack is Wack

At a time when United States President Ronald Reagan was declaring his infamous ‘War on Drugs’ while his wife Nancy Reagan encouraged people to ‘Just Say No’ one would expect Keith Haring’s public art Crack is Wack mural to be a welcome addition to the scenery of a drive south down the Harlem River Drive and not a controversial public art piece. While installed simultaneously to move local children towards drug-awareness, Haring’s unauthorized piece also unfortunately happened to coincide with New York City Mayor Ed Koch’s crackdown on graffiti. Putting the city firmly between a rock and a hard place with his Crack is Wack piece on the side of a handball court, Haring was enjoying a boom in his own career — being hassled by police while making his art (literally) underground in the subway, he was also selling the same works in galleries for thousands of dollars. Thus, the Parks Department fined Haring $100 dollars, something that the city would later apologise for, while asking him to recreate the piece as a permanent installation. You can see the work for yourself in New York City at East 128 Street and 2nd Avenue on both sides of a concrete handball wall.

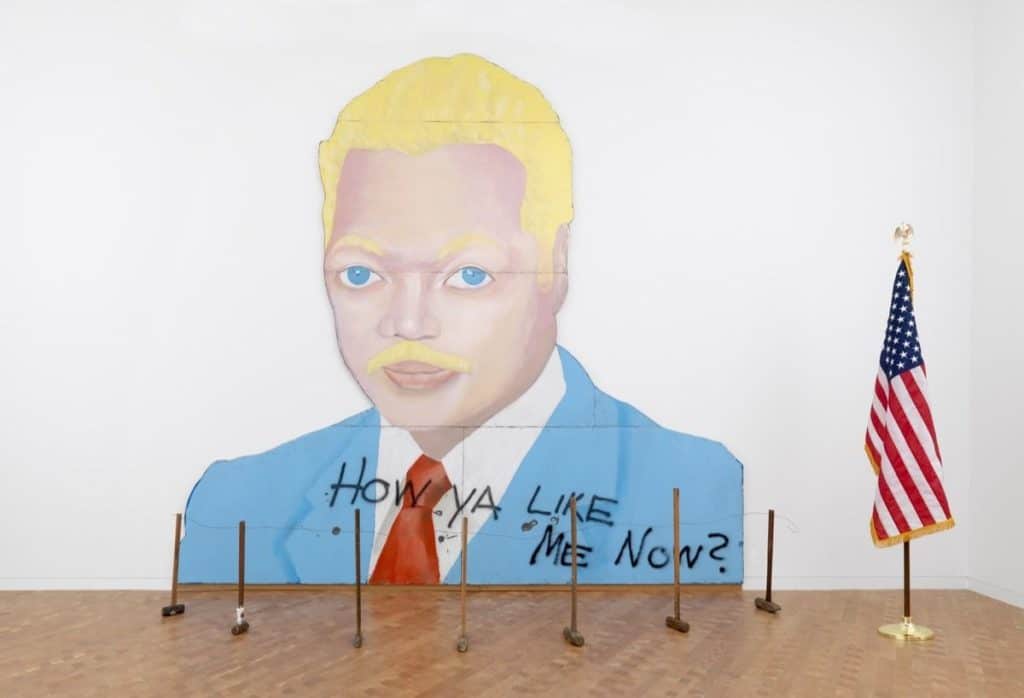

David Hammons: How Ya Like Me Now?

© David Hammons. Courtesy of Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland.

Conceived as part of a Washington Project for the Arts exhibition entitled The Blues Aesthetic: Black Culture and Modernism David Hammons’ How Ya Like Me Now first appeared on a tin billboard on a street corner across from the National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C. with no designation. Depicting Black civil rights leader Reverend Jesse Jackson with blonde hair, blue eyes, and white skin; with the lyrics from iconic eighties Rap artist Kool Moe Dee — How Ya Like Me Now — irreverently scrawled along the bottom. Though the huge 14×16 foot billboard was intended to provoke by displaying the whitewashed black leader next to rap lyrics; providing a juxtaposition that showed how popular culture was co-opting and commodifying black identity; local youths saw the work as racist and destroyed with sledgehammers. The piece has since been reinstalled within gallery walls, alongside a row of sledgehammers — ultimately incorporating the vandalism into the final work.

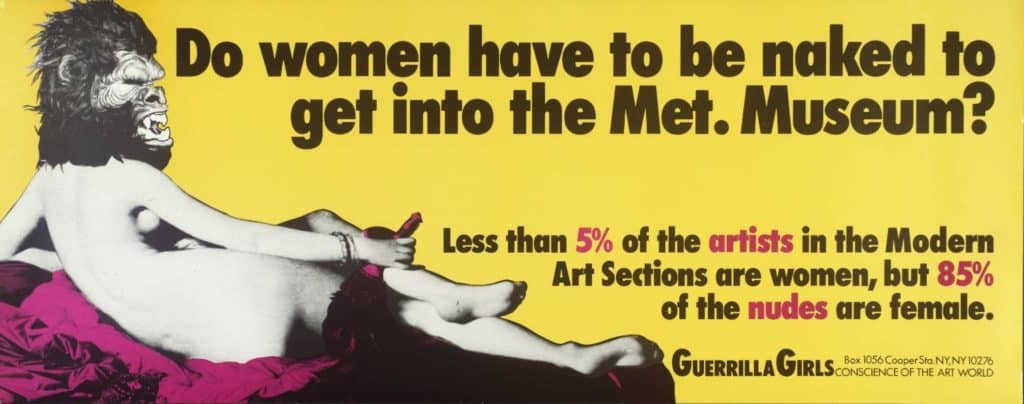

Guerrilla Girls: Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum?

When asked to design a billboard for the Public Art Fund in New York City the art-activist political feminist group the Guerrilla Girls found the perfect opportunity to critique the inherent sexism in museum collections and exhibitions. Inspired by the 1984 exhibition International Survey of Painting and Sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art that included the work of 169 artists, less than 10% of whom were women; the group set out to make a statement. Tongue-in-cheek but serious nonetheless, they conducted a self-entitled ‘weenie count’ at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where they compared the number of nude males to nude females on display; while also noting the dismal lack of representation of the work of female artists. Using the imagery from the 1814 Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres painting the Grande Odalisque the Guerrilla Girls took the subject from the painting and put their personalised twist on it — bedecking the concubine with a gorilla mask, as the artist group themselves were known for, and splattering “Do Women Have to be Naked to get into the Met. Museum? Less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art Sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female” across the controversial public art poster. Despite appropriating an oft-used image for the work the Public Art Fund rejected the piece. However, the Guerrilla Girls then rented advertising space on New York City buses, until the Metropolitan Transport Authority cancelled their lease, explaining that the image “was too suggestive and that the figure appeared to have more than a fan in her hand.”

Pierre Vivant: Traffic Light Tree

Originally installed at the junctions of Westferry Road, Heron Quay Bank, and Marsh Wall in Limehouse; French sculptor Pierre Vivant’s Traffic Light Tree can now be found in Poplar, London. The controversial public art piece came to be after a competition run by the Public Art Commissions Agency for the London Docklands Development Corporation under their public art programme. Replacing a plane tree dying of pollution, the Traffic Light Tree is comprised of 75 sets of traffic lights and stands at a towering eight meters. Each light, controlled by a computer, was originally intended to be linked to the hustle of the London Stock Exchange — but when that concept turned out to be too costly, the lights were calibrated to reflect the never-ending rhythm of the commercial, financial, and domestic activities in London’s Canary Wharf. Understandably, the Traffic Light Tree turned out to be exceptionally confusing to unsuspecting motorists trying to navigate the roundabout — leading some drivers to even take the roundabout the wrong way around! Ultimately though, the aesthetics of the piece won over the general public, and though tourists may at times be caught unawares by Vivant’s work, locals have cited it as one of the visually most pleasing roundabouts in the country.

Lei Yixin: Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial

A rousing controversy from start to finish the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial was subject to dispute even before its construction started. Firstly, Lei Yixin, a Chinese sculptor who was neither Black nor American, was chosen to realise the soaring sculptural depiction of the memorial’s subject. Yixin was a particularly controversial choice as, human rights activists pointed out, he had previously sculpted the Chinese communist revolutionary who became the founding father of the People’s Republic of China, Mao Zedong. Yixin then chose Chinese granite for the sculpture in defiance of many, most notably African-American artist Gilbert Young’s demands that the memorial be created by an African-American artist with American stone. The sculpture, crafted by reportedly non-union and uncompensated workers, when unveiled, revealed a botched paraphrased quote of King’s reading “I was a drum major for justice, peace, and righteousness.” when the original quote rang of greater humility and depth as, “If you want to say that I was a drum major, say that I was a drum major for justice. Say that I was a drum major for peace. I was a drum major for righteousness. And all of the other shallow things will not matter.” The backlash around the quote led to a nearly million dollar effort to remove it just a year later — the piece now stands with abstract striations where the quote once lay.

Paul McCarthy: Tree

Installed at the Place Vendôme in Paris in October 2014 as part of the FIAC’s (International Fair of Contemporary Art) Hors les Murs exhibition, Paul McCarthy’s Tree lasted only two days before vandalism brought the piece down. The 24-meter high inflatable sculpture purporting to be a green Christmas tree also bore a striking resemblance to a sex toy, a butt-plug to be exact, and the sculptor himself has since admitted that he deliberately shaped his piece this way as a joke. However, not all viewers found the work as funny as McCarthy, and less than 48 hours after its installation a vandal climbed the fencing around the sculpture and cut the power supply that kept the piece inflated, as well as the structural support cords. McCarthy did not want the work repaired or replaced but he exhibited Tree again in 2016 at Paramount Ranch 3 where visitors “reveled in its absurdist glory.” It would be remiss to not include one unexpected, and slightly hilarious result of the controversial public artwork: the boom in sales of real buttplugs in Paris. In fact a Parisian sex shop owner reported that while he usually sold 50 per month, in November 2014 (the month after McCarthy’s artwork went public) he sold over 1,000.

Anish Kapoor: Dirty Corner

Image: © Anish Kapoor.

Most famous for Cloud Gate (also known as “The Bean”) in Chicago’s Millenium Park, superstar artist Anish Kapoor is no stranger to controversy after securing the sole rights to use Vantablack, a pigment that was once considered “the blackest black”. In 2011 Kapoor exhibited his work Dirty Corner, a hulking steel structure 60 meters long and 8 meters high that visitors enter and progressively lose their perception of space as they move further in due to the darkness inside the piece. In 2015 Dirty Corner made its way to the Palace of Versailles where critics were turned off by what they reported as the ‘blatantly sexual’ nature of the work, that Kapoor himself described as “the vagina of a queen who is taking power.” The enraged critics vandalised Kapoor’s work with anti-Semitic slogans (Kapoor’s mother is Jewish), which the artist decided to leave to stand as an artefact of shame, and as a testament to the horror and intolerance of humanity. However, French officials ordered Kapoor to remove the graffiti, which he decided to do so by covering it in gold leaf, explaining it as “a royal response” to the vandalism and the sentiments it portrayed.

Anish Kapoor, Dirty Corner, mixed media, 60m x 8m, Versailles, 2015.

Ai Weiwei: Good Fences Make Good Neighbors

When the dissident Chinese artist Ai Weiwei was chosen by New York City’s Public Art Fund to create a citywide large-scale exhibition in 2017, everyone sensed it would be political in nature. Weiwei’s Good Fences Make Good Neighbors was in direct response to the anti-immigrant sentiments at play in America at the time, urging visitors to rethink preconceptions about the exclusionary nature of government policy. However overtly political the piece was, surprisingly its message garnered very little controversy, and the installation only became controversial public art when the time of year and location of exhibition was considered. A large-scale installation underneath the Washington Square Park triumphal arch had displaced the annual Christmas tree’s place of honour — angering those who felt that their holiday plans had been unnecessarily disrupted. The criticisms were met with a dismissive air from the Public Art Fund, an organisation that typically places great importance on working with local communities to ensure that the works receive positive reception, with President Susan K. Freedman admitting, “people upset about displacing a Christmas tree, that’s not something I’m sympathetic to.”

Relevant sources to learn more

Check out Curbed’s Best Public Art in New York City

Learn more about controversial art with 10 Controversial Artworks That Changed Art History or Controversial Art… Does It Get To You?