Articles and Features

Decolonizing Identity through Latin American Visual Art

By Anthony Dexter Giannelli

The story of Post-European contact art in Latin America has long been dominated by the inescapable shadow of colonization, where art forms paying tribute to the classical European tradition were hailed supreme by the ruling elite. From architecture to portraiture, non-Eurocentric creative thought and tradition were cast aside in exchange for a style resembling not that of the environment that the works exist in, but rather that of a ruler land far, far away. Thankfully, the tides have turned on this tired narrative, and an oppressive Eurocentric chapter has come to a close as we enter a new chapter of appreciation for decolonizing identity in Latin American art, reflecting the diversity of each artist’s own story.

An Abridged History of a Conquered Continent’s Search for its Authentic Voice(s)

After the rapid period of independence that swept through Latin American countries during the 1800s, the people of the newly freed lands, while by no means free from the lasting impacts of cultural monopolization by their colonial rulers, stood at the forefront of an identity crisis. The legacy of colonization and romanticizing of conquest dominated the visual vocabulary of artists and artisans for centuries and its effects can still be seen to this day. Answering the question of who we are and who we aren’t as ex-colonized peoples has left an expansive landscape to be explored through the canvas and beyond.

Movements such as Cubism and Abstract Expressionism quickly became the en vogue forms of artistic expression for Europe’s creative class during the early 1900s, with heavy inspiration from outside cultures and visual languages. The most notable example found in poster-child Pablo Picasso’s special relationship with traditional West-African mask work. Latin American artists trained in European cultural centres such as Paris saw familiar forms of indigenous representation take on new appreciation. Across Central America, the Caribbean, and South America, artists such as Rufino Tamayo, Wifredo Lam, and Fernando de Szyszlo recreated forms of human and emotional representation from their indigenous or Afro-Caribbean heritage that just years ago would have been deemed untalented or primitive by the Eurocentric, fine-art elites.

Finding an authentic voice and language to convey cultural struggle and pride led to the explosion of expression and wildly popular names of Mexican Muralism starting in the 1920s, with artists such as Diego Rivera composing vast expanses of struggles for solidarity, workers and human rights emboldened in an array of pre-Hispanic era mythological imagery. Frida Kahlo worked to further bring this visual language to the popular audience, to say the least. Her self-portraiture bringing facets of inner-identity to the surface enjoys a cult-like following to this day from the diaspora of Latin Americans searching for canvases of representation that reflect their own struggles with identity.

Fast forward to today, continuing a tradition of re-imagining and reincorporating symbols of pre-colonial power into the zeitgeist of their national heritage, images of indigenous monuments, mythological figures, and depictions of everyday life penetrate contemporary art of the region. Amongst these, Daniel Guzmán revisits Aztec deities of creation and earth, in a way that entertains the masses regardless of their knowledge of Mesoamerican mythology. Thus evoking raw, destructive, and creative forces at play as a sacred duality seen in goddesses such as Coatlicue. Guzmán’s emotion transcends a strict necessity for interpretation based merely on an artist’s ethnographic reference; we are rather drawn to the story of Guzmán’s charisma, humour, and personal narrative.

Artists not only create under the intimidation of ethnographic interpretation and fetishization of their work but also exist under the shadow of their modernist predecessors, as Peruvian artist Andrés Argüelles Vigo demonstrates in his work, Pintura Peruana (Peruvian Painting), showing a Google image search dominated by the recognizable traditional dress of the Andes and highlighted categories such as “colonial”, “indigenous” or “cholitas”. Presiding over the Google page is the figure famous work by Jose Sabogal, Varayoc. By manipulating the shadow cast over one’s own work by popular culture and art history the artist redirects focus back onto the individual and again opens up the dialogue to return to the reflection of a more personal search for identity.

The sentiment of looking inward for a more authentic interpretation of identity as a Latin American establishes a common ground for artists across the continent. Though the discussion of art in Latin America is often dominated by Mexican and Spanish American stories of mestizo artists reflecting upon their once-overlooked indigenous roots, ex-European colonies of Portugal and France draw attention to a Mestizaje story of their own, and their struggles with lasting deterring effects of colonial society on their freedom to find their own personal stories and identities.

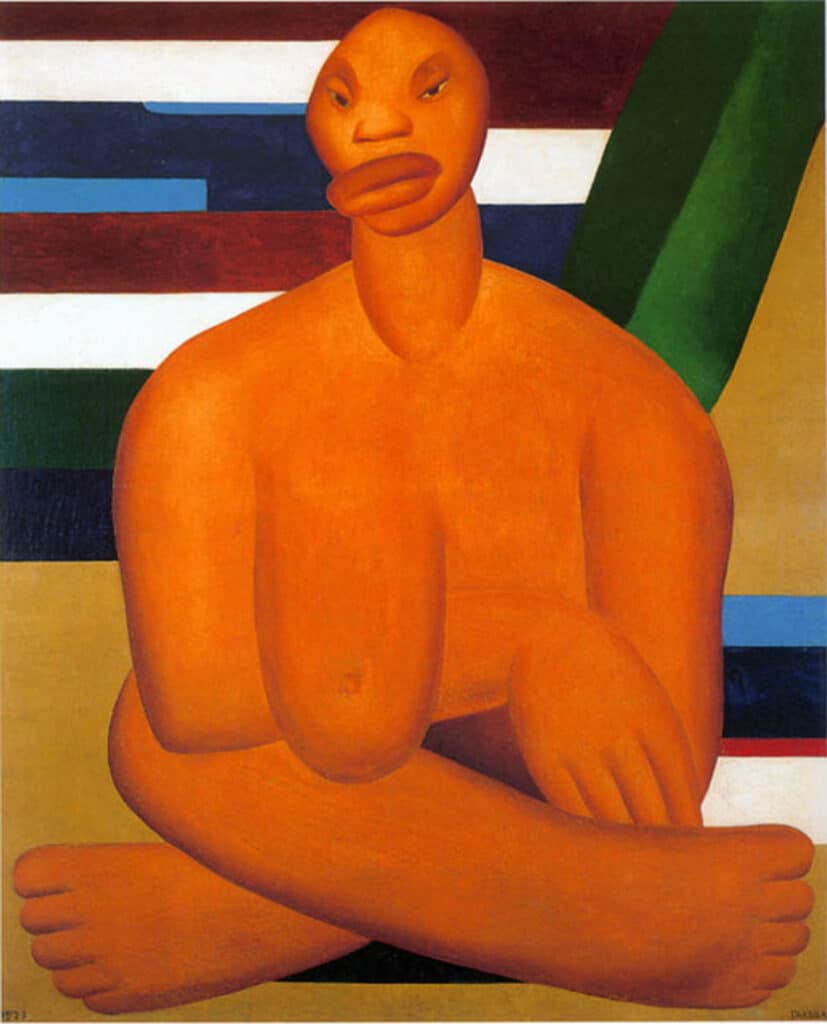

Celebrated Artists such as Brazil’s Tarsila do Amaral began to bring into question the centuries of predomination held over our view of bodies from a strictly conservative visual tradition reigned over by the Catholic Church. Images such as A Negra exist in stark contrast to the ethnographic caste style paintings – the first to travel to an outside world curious of what mystical outcomes came from peoples of separate races cohabiting a shared geographic area. Whether directly through colonial law or indirectly through societal rules, archaic pressure dictated the ways in which people related to their bodies and the outside world. Today artists such as Monica Piloni bring the policed bodies of women to the forefront, while in Haiti artists celebrate the freedom of the black body and in a synthesis of African spiritual tradition in corporal expression, captivating the contemporary art world.

Latin American Arts’ Legacy of Covert Resistance

Our initial premise, however, did not necessarily reveal the complete story. The treasured works of art, grandiose portraiture, stately architecture on surface-level did, in fact, present the familiar imagery of Euro-imperialists, but the hands of the guilds creating these works never ceased to underlay subtle glimpses of their own worlds under the surface. Thus, images conveying common themes in Catholic imagery, like the Holy Mother and Child, to an indigenous audience was laden with references. The mountainous composition of the dress in the Bolivian Virgin of the Victory of Málaga, for instance, evoked the Andean tradition of Pachamama – a deity representing mother earth. This case is not to be seen as a miraculous exception but rather an enlightening lens from which to reinterpret our understanding of Latin American art throughout the centuries. By presenting an outward image that pleased their colonizers, artists were able to ensure the survival of their culture and identities.

circa 1740. Denver Art Museum

Attempting to find a singular “authentic” narrative for arguably the most culturally diverse group of peoples will never be possible. From the German-Mexican Kahlo, the Chinese, Afro-Cuban Lam, each Latin American artist deserves the chance to share the story of their distinctly personal identity, and the respect from audiences to view it just as that, personal. Rather than continuing the practice of hiding beneath a superficial layer established by their colonial rulers, the art world owes it to Latin Americans to embark on a new chapter where their unique and diverse worlds are shown as they are in the forefront for all to appreciate.

Relevant sources to learn more

For more information on the topic of decolonizing art in Latin America, extensive research has been done on the part of Latinx art history and visual culture researchers such as Dr. Tatiana Flores.

You may also like:

A Short History Of the African Diaspora Through the Eyes of Its Visual Artists

What Can Contemporary Caribbean Art Teach Us About Diaspora and Identity?