Articles and Features

New Design Thinking: Gio Ponti’s Human Architecture

By Wieland Rambke

“Love architecture, the stage and support of our lives. “

Gio Ponti

A myriad of projects

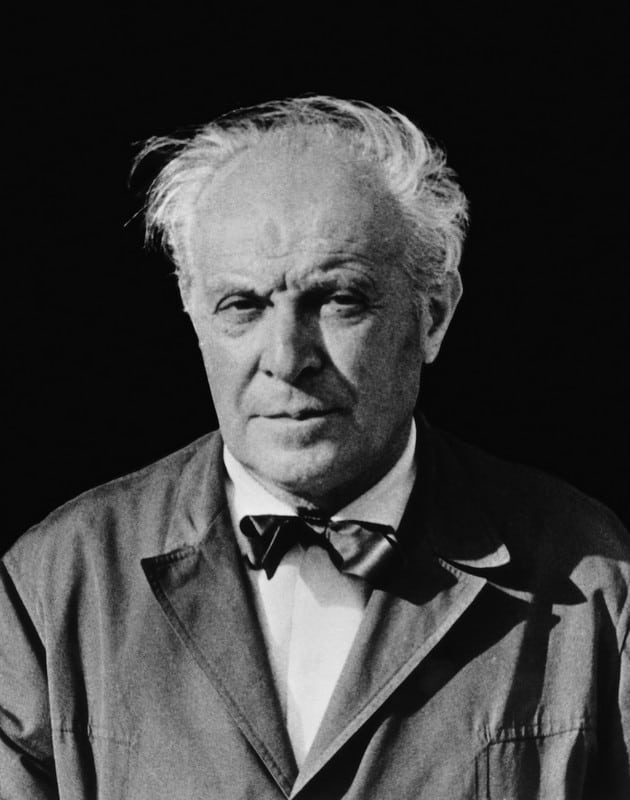

Versatile and prolific, Gio Ponti is an icon of Italian twentieth-century design, who produced a massive and outstanding body of work. Born in Milan in 1891, Ponti became an architect and industrial designer, an artist and a writer, a craftsman and a teacher, a lecturer and a publisher who would design anything from costumes to coffee machines. The list of his activities is an exhausting read. And a full listing of his works and achievements is in itself a monumental undertaking. A truly versatile mind, he avoided categories, styles and doctrines.

Giovanni “Gio” Ponti was never one to hide behind ideologies, but first and foremost, it was his healthy artistic instinct that drove his work. He loved art from an early age and dreamed of becoming a painter. Nevertheless, he decided to study architecture. This would give him a good balance between his creative inclinations and the desire for financial independence. Unlike other potential artists, this choice would not break his spirit as he wasn’t prone to cynicism or resignation. Instead, he would carry his artistic mind over into the fields of architecture and design, and allow both sides to stimulate each other.

“Architecture is a crystal”

Gio Ponti

Culture as Ingredient

Gio Ponti’s architecture studies at Milan Polytechnic School were interrupted by World War I. Irritated, he followed the draft but would return a decorated war veteran. A workaholic who survived on five hours of sleep, he graduated in 1921 with a degree in architecture but began designing furniture and home appliances. Shortly thereafter, his first buildings were commissioned. Moving away from his Neoclassicist roots, he reached some conclusions that would become part of the spirit of all his later undertakings: “Industry is the style of the 20th century.” He adopted elements of the Rationalist style, treating architecture as a branch of science. Rationalism as an architectural movement holds truth and beauty as central concepts, an approach that states that all worldly problems can be solved by reason.

Gio Ponti began promoting his views in the architecture and design review domus, which he founded in 1928. He loved Italy for its art and culture and would become an advocate of an Italian-style art of living, a combination of elements of the modern world with the distinct cultural heritage of Italy. His vision didn’t go unnoticed and soon caught the interest of Mussolini. In fact, while Hitler promoted “völkisch” and Neoclassicistic arts and crafts only, essentially turning Germany into a museum of itself, the Fascists were rooted in both Futurism and the history of the Roman Empire and had an interest in promoting their chimeric fusion of the speed of the modern world with imperial fever dreams; and it showed in their architecture. However, Gio Ponti wasn’t a political mind. He wouldn’t be bogged down in ideologies and would rather spend time exploring new materials than attend a rally.

In the 1950s, with the emergence of the economic boom, his activity became more prolific than ever; he built the Pirelli tower (1956–1960) in Milan, at the time of its inauguration the tallest building in Europe, and a hallmark of the city’s skyline still today. Commissions started to come from across the globe with projects in Sweden, Iraq, Brazil, the United States, and Venezuela, where he accomplished one of his masterpieces, Villa Planchart in Caracas: “a big butterfly poised on the hillside”, as Ponti described it.

Long-lasting and fruitful collaborations with artists and manifacturers also resulted in exceptional interior design innovations, both aesthetically and in terms of production system, never compromising on high quality of execution. His Superleggera chair produced by Cassina in 1957, has become a classic. Inspired by the principle of lightness, both literal and metaphorical, Superleggera’s legs are triangular in section and taper to give them maximum structural efficiency, and its back kinks delicately to allow a better seated posture; wood performs like aluminium, so light that a child can lift it with one finger.

Design for Humanity

Throughout his life, Ponti created a wondrous fusion of reason and beauty and rationally understood the value of beauty in everyday life. This went for his glasswork just as much as for his buildings, all united by the same enchanting quality: free, light, luminous.

Gio Ponti’s work is guided by a deeply understood Humanism and didn’t consider architecture as a tool to reform or deform people; in his own words: “Architecture is made to be looked at.” What is striking about his work is the emphasis on fluidity and applicability. He had no interest in telling people how to live their lives – indeed, a trait of all his work is the complete absence of any attempt at exerting power over people. Nothing in his work is heavy or burdening.

From his perspective, architecture and design were to serve humanity, not the other way around. This puts him at odds with a dominant current of modernity which is driven by an optimistic, at times violent lust for modernizing humanity itself. But who could really know and understand something as complex as humanity? Who could really fathom the depths of consciousness and unconsciousness? Gio Ponti, far from any preachy condescension, appreciated humans for what they are, And he sought to enrich their lives through beauty.

Relevant sources to learn more

You may also like:

Reimagining Spaces with Matrix Feminist Design Co-operative

The Art of Design: Iconic Designer Chairs Everyone Should Know

From Matisse to Rothko: Artist-Designed Chapels. A Religious Experience