Articles and Features

Agents Of Change: How the Sony Portapak Has Created A New Artistic Medium

By Adam Hencz

The Portapak would seem to have been invented specifically for use by artists. Just when pure formalism had run its course; just when it became politically embarrassing to make objects, but ludicrous to make nothing; just when many artists were doing performance works but had nowhere to perform, or felt the need to keep a record of their performances; just when it began to seem silly to ask the same old Berkleean question, ‘If you build a sculpture in the desert where no one can see it, does it exist?’; just when it became clear that TV communicates more information to more people than large walls do; just when we understood that in order to define space it is necessary to encompass time; just when many established ideas in other disciplines were being questioned and new models were proposed – just then the Portapak became available.

Hermine Freed, 1976

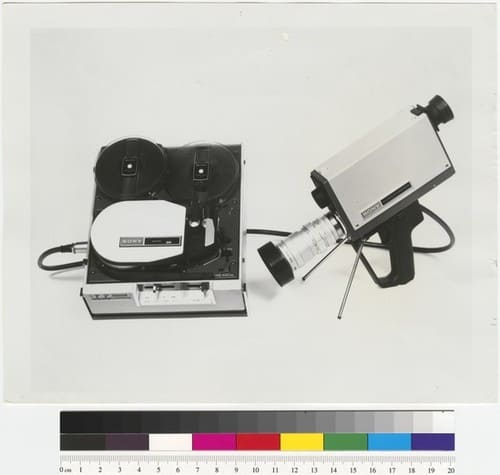

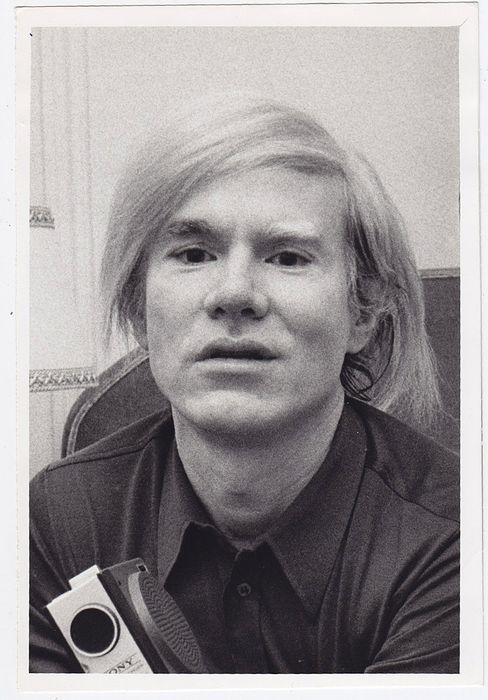

As technologies such as film recording, television, broadcast video and projection were developed and introduced, consumer electronics like video cameras and electronic mixers landed in the hands of artists and became tools of documentation, experimentation and creation. By co-opting the technologies of this medium, artists brought their own perspectives to the table and, for the first time, it became possible to detach motion pictures and video from the monopoly position of broadcasters. When in 1963 Andy Warhol began shooting footage for his first anti-film, an important piece for durational art titled Sleep, it was still an expensive and complex process to develop and broadcast films and videos by only a single artist and operator. Warhol used a Bolex 16mm camera that limited him to 30m reels, each lasting only three minutes. He spent months trying to learn how to operate the camera effectively and had to rely on crew members for post-production and release. It was a couple of years later, in 1965 when the Sony Portapak, the first highly portable, and relatively inexpensive video recorder became commercially available and swiftly became recognized by artists as an ideal tool for recording performances, happenings and tamper with video’s inherent properties as a metaphorical vehicle for articulating illusion and reality.

By the early 1970s, attracted by instant playback and recording of image and sound, and the potential of re-recording and erasure as a creative process, artists had begun to explore the possibilities and potential of the Portapak. Artists who took up working with video in this period like Nam June Paik, Joan Jonas, Bruce Nauman, Peter Campus, William Eggleston or Andy Warhol were highly influenced by movements and ideas from Fluxus, Performance art, Body art, Arte Povera, Pop Art, Minimalism, Conceptual Art, avant-garde music, experimental film, contemporary dance and theatre, and a diverse range of other cross-disciplinary cultural activities.

The brief history of the Sony Portapak

Initially developed and introduced by Sony Corporation – the then-young but blossoming Japanese electronics company – in 1965, the Portapak was a highly portable, and relatively inexpensive black-and-white open-reel video recorder with a dedicated camera. There were several versions of the Portapak introduced around the world and its different formats were incompatible with each other, therefore dedicated creative hubs using each edition were formed both in Europe and the USA. Its portability and ease of operation made it ideal for use by an individual operator, and artists could work with it on their own in the privacy of their own studios since no technical crew or expensive and burdensome lighting was required. As its poetic manual put it: “The portable video system represents the essence of decentralized media: one person now becomes an entire TV studio, capable of producing a powerful statement”. In the early days of video, artists’ tapes were most often continuous unedited recordings, the documentation of performances or presentations made live to camera with a simple ambient soundtrack or often the human voice. In many of these tapes the corresponding relationship between sound and picture was perceived as an important asset. The Portapak ensured the unity of sound and image and its built-in mike was often used as if it were an extension of the microphone, with synchronous sound being an integral part of the audio-visual experience.

Pioneers of video art using Sony Portapak

Nam June Paik

Mythology surrounding the origins of video art revolves around Nam June Paik’s purchase of the Sony Portapak upon his arrival to New York City. Rumor has it that his first use of it was to record images of the Pope’s visit to the city from the back of a taxi. Paik showed the footage that very evening at the Cafe Au Go-Go in Greenwich Village. What eventually became clear is that Paik purchased one of the earliest Sony Portapaks available in the US and showed his first recording in 1965, establishing video as a credible medium for artistic expression. His earliest extant tape that remains available is Button Happening (1965), a one and a half minute recording from that year, documenting a single performance action in the spirit of conceptual Fluxus humour: Paik buttoning and unbuttoning his jacket.

Bruce Nauman

In 1967, Bruce Nauman made his ten-minute, 16mm film Walking in an Exaggerated Manner Around the Perimeter of a Square. Using a Sony Portapak camera borrowed from the gallerist Leo Castelli, Nauman recorded himself slowly traversing lines of masking tape tacked to the floor of his studio. Stepping one foot in front of the other, and with an overstated sway of his hips, he repeatedly paces the boundaries of his temporary square. The position of the camera is static and the video is silent aside from the melodic, repetitive whirring of the rolling film. In the following years he used the camera for his experiments with time and process by recording similar simple physical actions such as running, pacing, balancing, throwing and catching a ball, manipulating a fluorescent tube, repetitively playing a note on a violin, or falling into a corner.

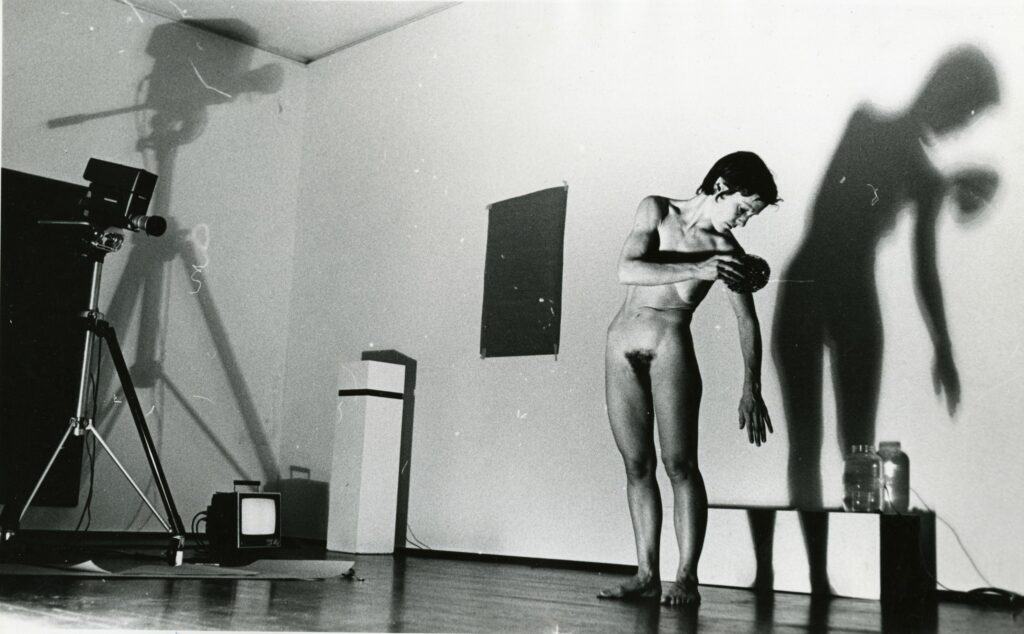

Joan Jonas

In 1970, sculptor Joan Jonas travelled from New York to Japan and discovered fourteenth-century Noh theatre as well as bought a Sony Portapak video camera. After her visit to Japan, the artist began using the video equipment as an integral part of her dance performances. Extending her practice of using mirrors and masks in her live performance, video enabled Jonas to explore a further level of reflection, relating this experience to her audience via live video transmission. Vertical Roll (1972) is her recording of a performance made in front of a video monitor which is displaying the recording of a previous performance on a maladjusted monitor on the floor of the artist’s studio. Jonas’ Organic Honey’s Vertical Roll (1972) also involved recording previously recorded material as it was played back on a television, with the vertical hold setting intentionally in error.

The monitor, at that time a critical factor of video, is an ongoing mirror. I explored image making with myself as subject: I said ‘this is my right side, this is my left side,’ and the monitor shows a reversal. I made a tape about the difference between the mirror and the monitor […] I worked with the qualities peculiar to video – the flat, grainy, black and white space, the moving bar of the vertical roll and the circle of circuitry formed by the Portapak, monitor/projector, the artist.

Joan Jonas

Peter Campus

American artist Peter Campus’ Double Vision (1971) combined the video signals from two Sony Portapaks through an electronic mixer, resulting in a distorted and radically dissonant image. In 1973, he created and performed Three Transitions that became one of the seminal works in video. In three short exercises, Campus uses basic techniques of video technology and his own image to create succinct, almost philosophical metaphors for the psychology of the self.

William Eggleston

Photographer William Eggleston bought two Sony Portapaks and after tinkering with his camera and adding different lenses, over a period of two years, shot about thirty hours of material that was edited into his pioneering video work Stranded In Canton. Shot in 1974 the piece documents a cast of outcasts, drunkards, and artists on the American South, with the intimacy, ease, and instability of an informal participant.

Decentralization, flexibility, immediacy of playback, speed of light transmission, global transmission pathways, input to two of the senses – these are characteristics not yet shared by any other medium.

John Hopkins and Sue Hall

The early Sony Portapak was taken up by many artists because of its ease of operation, compact portability, and its synchronically combined sound and image. Since the particular configuration of this early video format made editing difficult and inaccurate, many artists worked in real-time, or re-recorded sequences to create more fluid and less fragmented videotapes. Artists devoted attention to the Sony Portapak camera itself — for example in The Portapak Conversation (1973) made by the Videofreex collective, and Douglas Davis’ The Cologne Tapes (1974) — as well as the phenomenon of the perception of the image using simple technical tricks, such as Dan Sandin in the video Triangle in Front of Square in Front of Circle in Front of Triangle (1973). The nature of videotape recordings also provided artists with new means to challenge and critique the increasingly commodified art market, ultimately offering new possibilities for imagining reality.

Relevant sources to learn more

History of Video Art

An Abridged History of Video Art Part I. The Conceptual Pioneers, from the 60s to the 80s

A Short History of Video Art Part II: Stories Of And For Our Times

Female Iconoclasts: Shigeko Kubota, the Mother of Video Art