Articles and Features

The Checklist, Vol. 3: an Exhibit at ICA Gallery, London, 1957

William Pym, The Checklist, Volume 3

Art history, like world history, looks different depending on where you’re standing and what matters to you. The monolithic western canon has been chiseled into a prism, absorbing and reflecting new narratives and new histories. This is a good thing. Fashion, a sexy blur, drives the conversation about contemporary art in culture, and consensus is rare and temporary. This is a fine thing. Money and the art market tie us in knots and cloud our judgement, because the latter is easily manipulated by the former. This is a bad thing. Mush all these factors together, and a solid art history seems both more elusive and more necessary than ever. This column, The Checklist, looks at an exhibition from the past via facts that cannot change: artwork, space, audience, a moment in time. The goal is to cut through the noise, and to remember that art is a gift.

an Exhibit

Richard Hamilton, Victor Pasmore, Lawrence Alloway

ICA Gallery

London

13-24 August, 1957

British Pop Art of the early 1950s is seen in a different light than the early 1960s American Pop of Warhol, Lichtenstein and Oldenburg, with all their indelible icons. The American Pop movement created defining images of the 20th century by commemorating a cresting moment where consumerism, desire, beauty and the object all came together. The early Pop movement in the UK was less of a full-out embrace of new brave capitalism than a period of discovery, of artists feeling their way out of the rubble and discovering comfort in culture during the first austere postwar years. Told through a strange, singular nine-day exhibition in London in 1957, this month’s checklist is about the point British Pop Art reached before the conversation gave way, and found its true home, in the US.

*

Richard Hamilton was a gifted draftsman and thinker who had kicked around and been kicked out of art schools in the ’40s. He found a groove with the Independent Group, a niche but unexclusive cabal of artists, architects, and historians who met for two yearlong ‘sessions’, meaty congresses on a theme with a range of speakers, from 1953 to 1955. The Independent Group were interested in science and technology and a certain inclusivity in art. It was a modern position held by a group of like-minded people who were bored of the elitism and sluggishness of the academy and keen for art exhibitions that all people could see and enjoy. Hamilton made his name as a wizard at making these sort of exhibitions. His 1951 exhibition Growth and Form, at the ICA in London, was what we would now call a multimedia display, a sense-enveloping visual essay on scale and form in the natural world. With lightboxes, projections, dramatic architecture and wild shifts in scale, Hamilton’s eye was on the design of experience, the connections we make between images and the energy it creates, and how we participate in the synaptic science of seeing and learning. Growth and Form was both academic and general-interest.

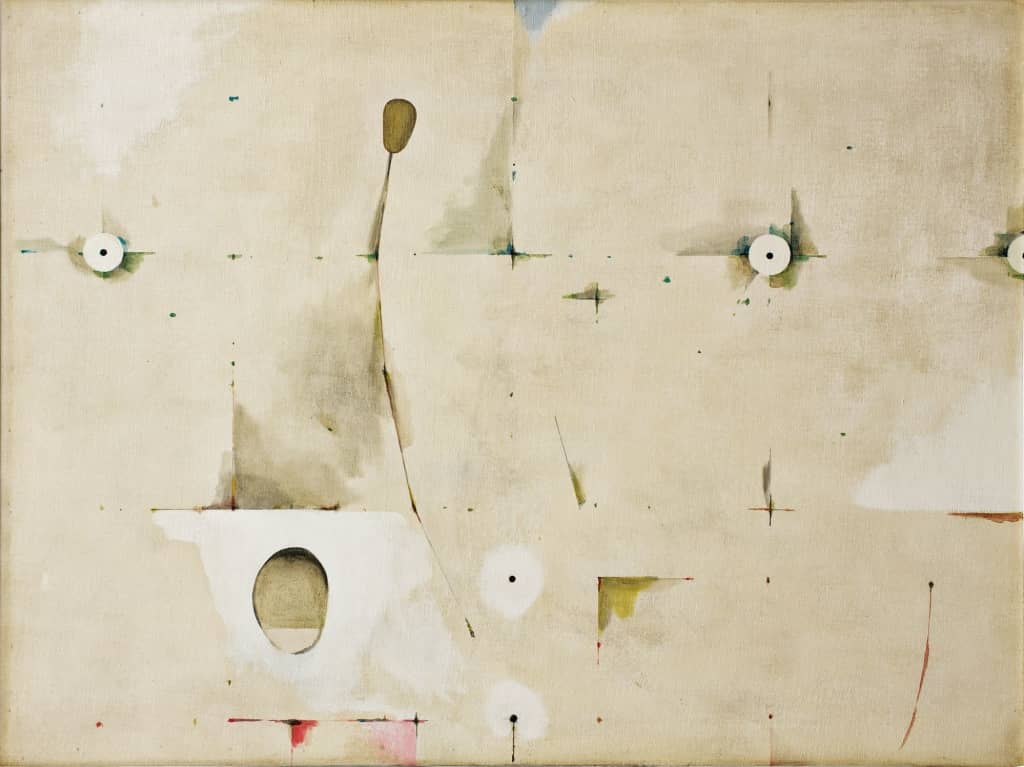

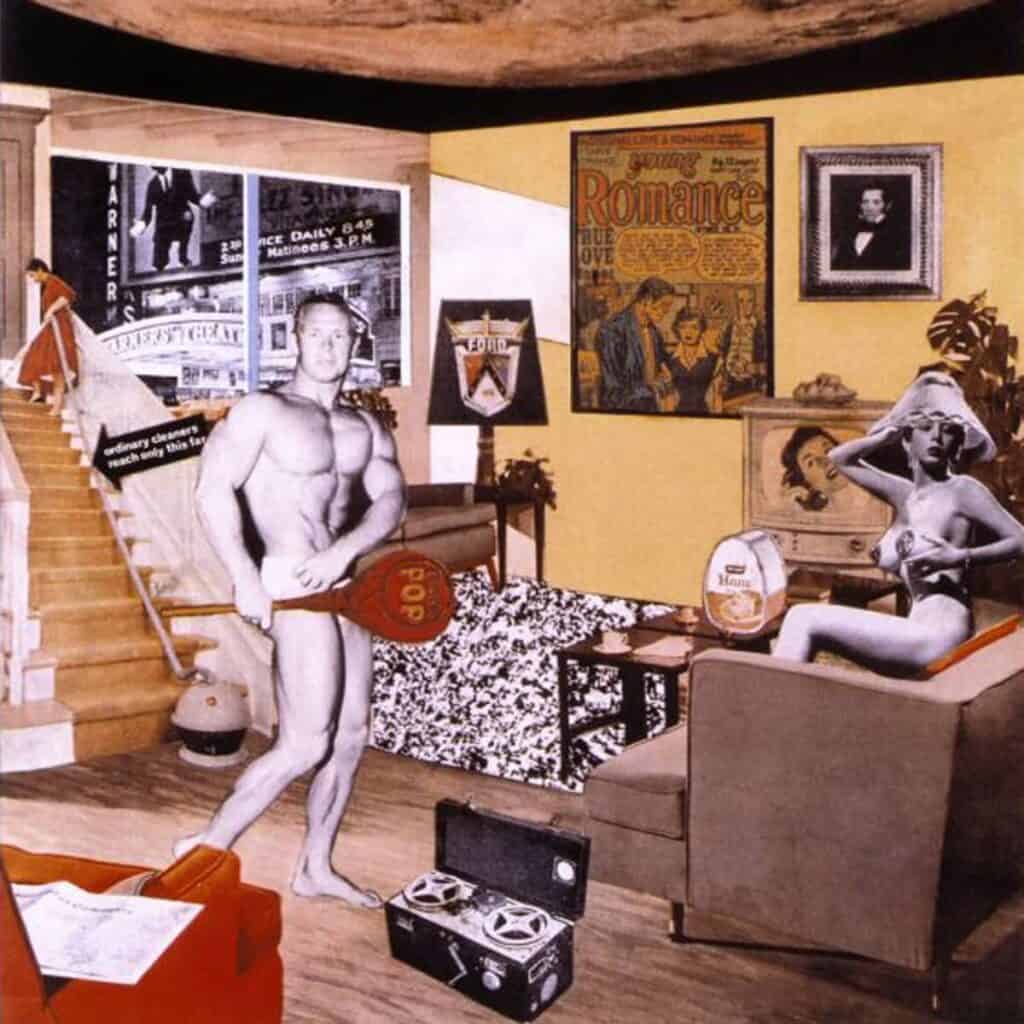

Hamilton revelled in fine details in his own art objects in the early 1950s; he was clearly caught up in the bubbling, fresh fetishization of consumer culture. There was an irresistible pull to this emerging world of ownership and goods, which brought nothing but beauty and promise into Britain rebuilding, bleak and still weak, after World War II. This world was a beacon in the postwar years, with bounty and modern life available to all, and it touched everything Hamilton did. The early painting Respective, from 1951, is a neurotically precise work of Modernist geometric abstraction, a little Miró, a little Constructivist, all holding the eye with a tense, thoughtful control. This painting also, patently, represents an upholstered sofa tufted with buttons. Whether it is acknowledged as the subject or not — the scholarship on this work largely focuses on Hamilton’s pursuit of a ’scientific aesthetic’ left over from the teaching of the eminence Walter Bayes at the Royal Academy — Hamilton traced the lines of desire and conjured their feel at their most pervasive level. Hamilton couldn’t hide from the form of modern life. It was everywhere, and he was locked in. “Even his flirtations with abstraction,” per Isabelle Moffat’s definitive 2015 essay for Mousse magazine, “left iconic traces intact.” Five years later, Hamilton made a collage of a fully appointed modern domicile entitled Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? This work, as the cover of the catalogue to the key British Pop exhibition This is Tomorrow in 1956, is an emblem for the potential of moment. Yet Hamilton had been answering this question for some time in his work: the appeal of today’s home is in stuff, and our access to it. It feels good, and in telephones and tennis rackets and home stereos, its forms were taking over our world. Hamilton’s work gravitated toward it. There was no escape.

an Exhibit, presented in late summer at the ICA’s original home on Dover Street, was a collaboration between Hamilton, the true-believer abstract sculptor of the prior generation

Victor Pasmore, and the critic/curator Lawrence Alloway. This sort of collaboration was very much in the tradition of the Independent Group and the community it had fostered earlier in the decade. Pasmore had urged Hamilton to make something neutral, pure, absent of what would 10 years later be known as signifiers. No message, just exhibition. Hamilton’s response was to hang acrylic panels of varying transparency and a few colours, all the same size, from the ceiling at all possible 90-degree angles. A geometric intervention.

It is unclear how these forms felt, or what it was like to be in the space. Documentation is very scarce, and we’re left with mercilessly few angles on the event. One might imagine that the sightlines caused the eye to play with perspective and triggered the filtering of light and colour. Maybe it didn’t work like that. It might have had some Bauhaus energy, back to the vibrant innocence of an earlier industrial age. Maybe it was a spectacle — maybe it wasn’t. Maybe you could navigate it like a maze, maybe you just stood and looked at it. The show was billed on the private view invitation as ‘a game, an artwork, an environment’. No further details were given.

It’s not just the lack of documentation, however, that makes an Exhibit so difficult to interpret. It is the fact that it is aloof from critique. It pulls off this feat because it does not invite critique. Now as then, an Exhibit truly is free from message, from meaning. It has no accent, no affect, no style or stance. Hamilton was an artist who couldn’t resist the charged excitement of new popular stuff and the way it enlivened the cultural experience, but he paused for this artwork to gather people around the purity of a shared experience, without the stress of discourse, cultural gatekeepers, or being hip. It was about what the new culture could do, rather than what it looked like. It brought people together. an Exhibit championed the audience, the whole audience. No one understood it any better than anyone else.

an Exhibit’s legacy is as a democratised artwork. The democratised artwork tastes the same to everyone, like Warhol’s bottle of Coca-Cola. As such, an Exhibit is an early example of Pop’s great radical ideal of dissolving the walls of the museum, and letting the world in. This artwork, with nothing to do with the trappings of popular culture but everything to do with modern populism, can stand as a foundation of Pop Art. As an oddity in 20th-century art history, an Exhibit serves as a quiet breather, a palate cleanser before the imagery revolution of the 1960s, while also embodying the best of what that revolutionary art could be. Hamilton knew there was no turning back, no escape from the modernity that inspired his art throughout the decade. an Exhibit thus served as a visual memorial to a world unsaturated by products, and as an aspirational preview of all the positive cultural change that Pop would bring. This was British Pop’s signature: to bridge the gap from one world to another, and to track the changes as the western world transformed.