Articles & Features

Appropriation! When Art (very closely) Inspires Other Art

By Tori Campbell

Appropriation Art

With the bold intention of repurposing existing and often iconic artistic imagery, those who create appropriation art borrow or copy in order to reframe it and make it their own. Whether it be a commercial artefact like a soup can, or a universally recognisable piece of fine art; appropriation art has been around for centuries, though the mid-20th century rise of consumerism led to a newfound significance and prevalence. Join us in exploring some of the most iconic works of appropriation art in contemporary art history.

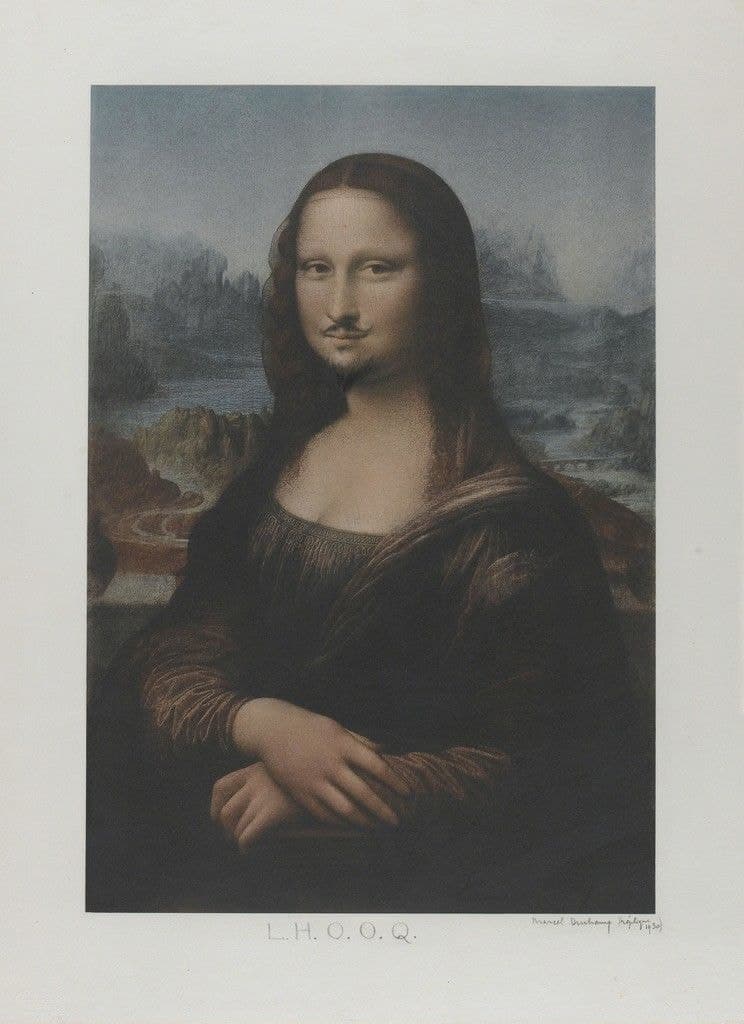

Marcel Duchamps’ L.H.O.O.Q.

First conceived in 1919 as one of his infamous readymades, Duchamps’ term for his artistic process that took everyday objects and reformulated them to be seen in a new perspective, L.H.O.O.Q. is a postcard reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s ubiquitous Mona Lisa which has been doodled upon to include a moustache and beard in pencil. Recreated multiple times throughout his career, in various formats; the works’ title L.H.O.O.Q., is in itself a joke, when the letters pronounced in French sound out “Elle a chaud au cul“, the equivalent of crudely saying “she is horny.” By reformatting the Mona Lisa on the cheap postcard to have masculinised features, Duchamp is able to poke fun and question preconceived notions of both gender and high art.

Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing

Truly a collaboration between three artists: Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, and of course, Willem de Kooning; Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing gives the audience exactly what they would expect. Confronted with a smudged but blank piece of paper framed with a simple inscription of ““ERASED DE KOONING DRAWING BY ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG 1953”, the process of creation for this piece may be more captivating than its eventual appearance. Having previously experimented with the concept of drawing negatively by the removal of pencil marks with an eraser, Rauschenberg decided that this idea could only come to a truly satisfying fruition by erasing a universally renowned artists’ work; that of Willem de Kooning. Though originally trepidatious, de Kooning agreed, as he determined that he did not want to get in the way of another artists’ creation. After its initial exhibition in which there was no inscription at all Rauschenberg ultimately coordinated with Jasper Johns, and the inscription eventually came to be a part of the work itself.

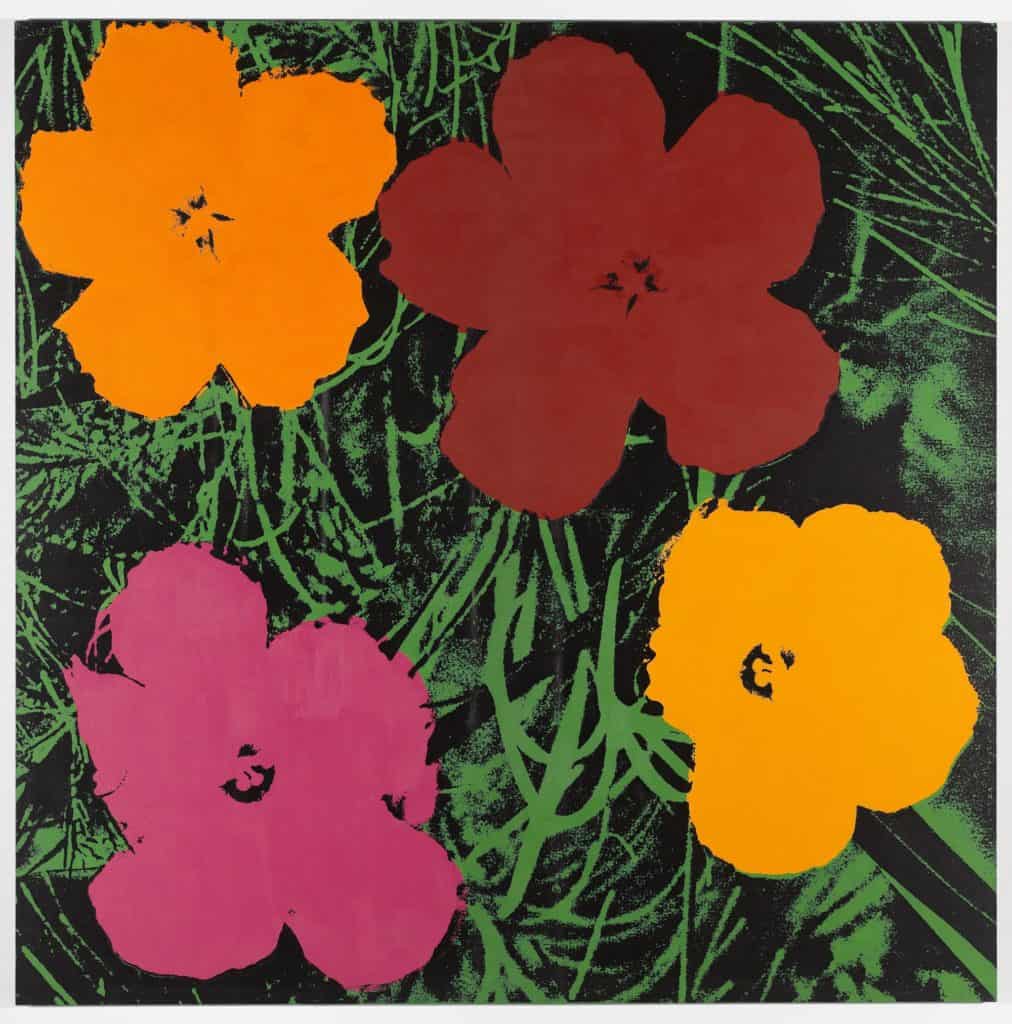

Elaine Sturtevant’s Repetitions

Creating self-described Repetitions artist Elaine Sturtevant crafted replications of her famous male artist peers’ works. Focusing her efforts on the sculptures of George Segal, and striped paintings of Frank Stella, her most iconic pieces are those that replicate Andy Warhol’s Flowers series. By coordinating her efforts with Warhol himself, Sturtevant was able to quietly utilise his original silkscreens to craft her images — allowing an exact replication that allowed her audiences to experience the disorienting feeling of viewing an “authentic” Warhol, but one created under the aegis of another. By creating appropriation art out of her male colleagues’ works she was able to make a feminist statement while also ruminating upon the concepts of originality, copyright, and artistic ownership.

“Remake, reuse, reassemble, recombine—that’s the way to go.”

Elaine Sturtevant

Richard Pettibone’s Modern Classic Miniatures Series

Beginning in the 1960s Richard Pettibone began replicating the works of pop artists such as Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, Frank Stella, Roy Lichtenstein, and many others. With an initial focus on pop art, he created his miniature versions of the newly-famous masterworks. Eventually, Pettibone moved into replicating, in miniscule scale, modern and contemporary art masterworks regardless of art movement, including sculpture as well as painting in his repertoire. Utilising handcrafted stretcher bars to realise his tiny canvases, Pettibone created new and painstaking ways of viewing well-known post-war pieces. His works, dubbed ‘art historical referencing’ by critics mirrored the model trains he loved in his childhood — and though they spurred many controversies and discussions on originality and ownership, his pieces evoke the feeling that imitation is sincerely the highest form of flattery.

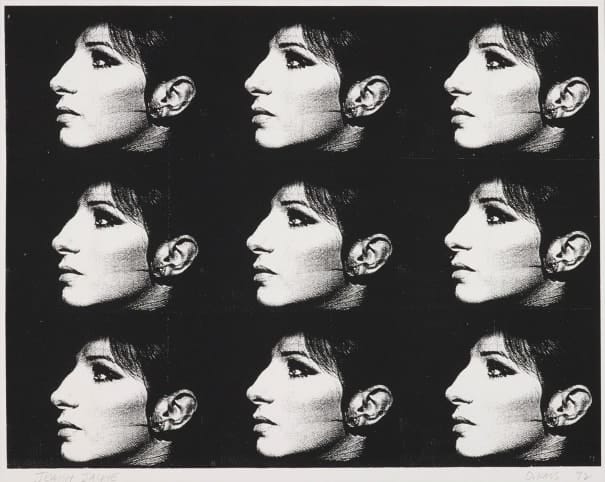

Deborah Kass’ Warhol Project

Appropriation artist Deborah Kass began her new series The Warhol Project in 1992. Based on the mass produced screen prints Warhol created in the 1960s Kass took this universally-recognisable stylistic language and turned it on its head, using significant women in art and culture as her subjects. By depicting artists and scholars that were her own personal heroes (such as Cindy Sherman, Barbra Streisand, Elizabeth Murray, and Linda Nochlin) in place of sitters like Jackie Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe, Kass was able to create a feminist revision of art history through the imagery of one its most famous male protagonists. With other works she directly and boldly challenged the traditions of patriarchy — in replacing Warhol with herself in his self-portraits she confronted gender representations in art and an alternative history where powerful women are seen at the fore.

Richard Prince’s Cowboys Series

Equally fascinated and disgusted by the shiny advertisements in print magazines, painter Richard Prince decided he wanted to replicate them. In his exercise of rephotographing and reimagining the ubiquitous imagery of commercialism; Prince undermined the appearance and feasibility of such images, focusing on the impossibility of the realities advertisements were seeking to sell. Prince’s Cowboy series, a riff on the classic American Marlboro man, is his most recognisable and infamous in his deconstruction of modern archetypes in advertising and consumerism. Astride a perpetually running horse the cowboy goes nowhere, mirroring the artist’s disgust and disapproval of the futile materialism of the decade.

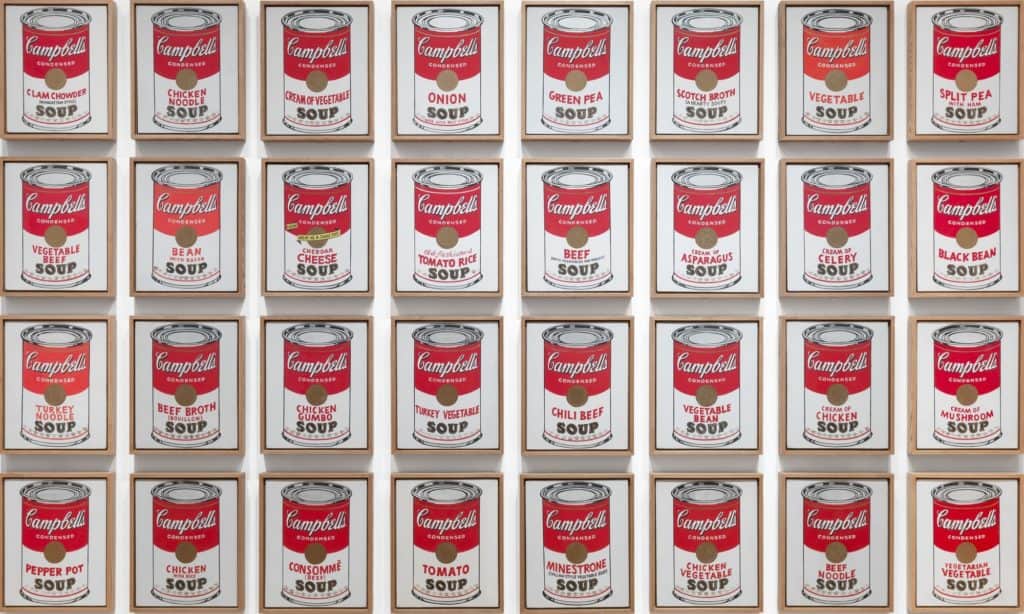

Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans

Thirty-two canvases, one for each of the flavours of canned Campbell’s soup, comprise Andy Warhol’s infamous Campbell’s Soup Cans. Utilising a combination of projection and tracing with painting and stamping Warhol replicated the nearly identical image thirty times over — stressing the ubiquity of the products’ appearance and calling into question the originality of art. No stranger to the appropriation of consumerist imagery, Campbell’s Soup Cans were some of Warhol’s final painted works, before he discovered the silk screen printing technique that he would employ to realise the majority of his oeuvre. A firm believer that art should belong to the masses, Warhol’s appropriation art helped to define Pop Art as a movement, and in turn became a frequent target of appropriation artists himself.

“I used to have the same lunch every day, for twenty years, I guess, the same thing over and over again.”

Andy Warhol

Louise Lawler’s Pictures

Part of the Pictures Generation, Louise Lawler displayed her appropriation art alongside legendary artists including Cindy Sherman, Sherrie Levine, and Jack Goldstein in an influential 1977 exhibition that called into question the concepts of ownership, production, and circulation in art. Lawler developed her style in the 1980s when she began taking photographs of other artists’ original artworks. Her re-presentation of such works, photographed in museums, storage spaces, auction houses, and even private homes; tackles the monetary and intangible value of art — and its role in society. In her appropriative piece Does Andy Warhol Make You Cry? which is a photograph of Andy Warhol’s 1962 Round Marilyn, complete with auction house price tag, Lawler asks her audience to confront the emotional and financial effects of Warhol’s work.

Mike Bidlo’s (Not) Series

Controversial appropriation artist Mike Bidlo is well known for his recreation of paintings by 20th century masters. His (Not) series is comprised of painstakingly recrafted works by artists including Pablo Picasso, Fernand Leger, Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, Jackson Pollock, Georgia O’Keeffe, Giorgio de Chirico, Constantin Brancusi, and, of course, Andy Warhol. By copying the artist’s subjects and styles with exacting detail, Bidlo confronts the concept of authenticity within fine art — challenging the modernist ideologies of exclusivity and originality by focusing on the act of creation instead of the final product.

“Tight-assed art historical taboos…I’m interested in exploring and penetrating those taboos.”

Mike Bidlo

Cindy Sherman’s History Portraits Series

From 1989 to 1990 Cindy Sherman experimented with her History Portraits series. Clad in elaborate costuming Sherman photographed herself as the iconic subjects of renowned historical works, ranging in subject from Madame de Pompadour to Caravaggio. Sherman’s Caravaggio as Bacchus is particularly interesting as it is one of the first times she took on the disguise of a male character. With heavy makeup, costume, and prosthetics; Sherman takes on the role of Caravaggio, who himself assumed the role of the Roman god of wine, Bacchus.. By layering these personalities and identities, Sherman reminds the audience of the patriarchal-lens of art history.

Relevant sources to learn more

Learn about Appropriation Art from the Tate

And learn even more from the MoMA

Check out our piece on self portraiture