Articles and Features

Art Pranks: Between Imaginary Artists And Sneaky Exhibitions

“Harvey Stromberg is a photographer. Or a media manipulator. Or a self‐made chance factor. Or an impresario. Or a guerrilla activist. Or a fraud. All of the above. None of the above”.

The New York Times

Try to consider to what extent the context of one’s experience of art affects the perception and the appreciation of it. Would you still recognise and praise a masterpiece away from an institutional setting? Conversely, if a distinguished figure in the art world championed an artist’s work, would you have the nerve to claim the opposite? Partly scams, partly veritable works of art, a series of pranks have bared the weak links and incongruities of the art system, also unveiling people’s pathological desire not to appear foolish or out of the loop.

Pranking the Museum of Modern Art: the longest-running one-man photo exhibit

On the evening of June 15, 1971, a crowd gathered in front of the MoMA to join the opening of what the New York Times would describe as the “longest-running one-man photo exhibit”; although, at a first glance, no official show seemed to be running.

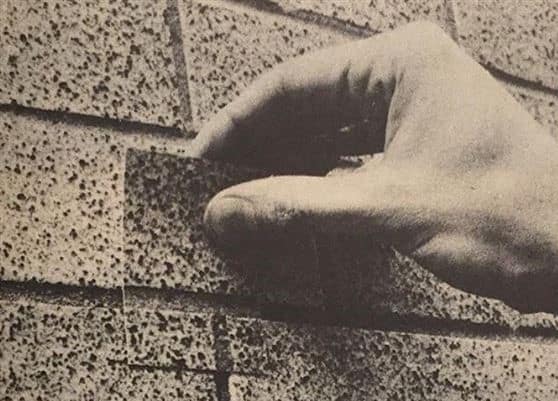

The fact was that the photographer Harvey Stromberg had been installing his ‘photo-sculptures’ all over the prestigious museum under the nose of the museum personnel for over two years, ultimately deciding to throw himself an opening party to celebrate his achievement. He had put on three-hundred life-sized photographs of the equipment such as light switches, bricks and keyholes, sticking them where it was more expected to find the reproduced objects.

Before the ‘show’, he had spent some time in the museum, taking measures and pictures of the utility objects and then repeatedly went back to put his photographic trompe l’oeil in place. “I like the museum to find them – he admitted – then they realise there is a game going on. I also hope people steal them and claim they have stolen art from the Museum of Modern Art”.

The reason behind his prank? As Stromberg put it: “I really have fun doing it. When I install a piece, my adrenalin is racing. In fact, it is very hard for me to come up with serious reasons why I do it”. However, critic Harold Rosenberg has ironically pointed out that “if it is in a museum, it is art”. Then why not consider it as such?

The 2001 Tirana Biennial

In a country, devastated first by war and then by economic chaos and social instability, a biannual cultural event seemed to open new, optimistic prospects for Albania, aiming to establish a cultural exchange of a global dimension and a privileged meeting point for art.

With no existing contemporary art infrastructure and the limited budget of $30.000, the first edition of the Tirana Biennial took place from September 15 to October 15, 2001.

“After all the big-budget art events, this is a real art exhibition without budget but with real artists and real works” was the motto.

Under the direction of Giorgio Politi, then editor of Flash Art, thirty-four curators independently selected and presented the work of over 200 artists from all over the world reflecting on the challenging theme of ‘Escape’ in its multiple variations, from migration to psychological alienation.

Among the curators were illustrious name of the art scene such as Hans-Ulrich Obrist, Vanessa Beecroft, Maurizio Cattelan, Jan-Erik Lundstrom, and the photographer Oliviero Toscani.

The latter had personally reached out to Politi and, following an intense email correspondence, had been ultimately invited to join the event as a curator and designer of the Biennial official poster. Toscani’s design provocatively showed a distorted reproduction of the Albanian flag, such a controversial icon that it was immediately rejected by the Balkans art institutions as inappropriate and potentially problematic, but later reconsidered on account of the support provided to the determined designer by the Biennial coordinators. The poster’s provocative character, however, was nothing compared to the artists Toscani championed: an Islamic fundamentalist, Hamid Piccardo; a confessed paedophile, Dimitri Bioy; a producer of amateur porn videos, Carmelo Gavotta; and the Nigerian Bola Ecua who illustrates the horrors of her country in gory images.

Toscani’s curatorial selection turned out to have bad timing, as the international exhibition took place only a few days after the attack on the Twin Towers, making the promotion of an artist defined as the ‘Jihad spokesman in art’ – Hamid Piccardo – as well as at the distribution of invitation cards to the Biennal showing the picture of a smiling Osama Bin Laden, an even more questionable choice. Understandably, many raised their eyebrows, and Maurizio Cattelan decided not o participate in the event at all as a sign of dissent.

Despite the debate, the Biennal was inaugurated, the catalogue printed and distributed. It was only then that Oliviero Toscani received it by post in total astonishment, as he had never had anything to do with the Tirana Biennial, nor he had got in touch with Politi in the first place.

Both he and the Biennal organisers had been victims of an anonymous prankster who had stolen Toscani’s identity and then invented the ones of the four artists from scratch in what many have interpreted as an artistic action against the art systems and the arbitrariness in selecting who should be considered and praised as an artist.

The photographer pressed charges against unknown suspects and still today the prank’s perpetrators remained unknown.

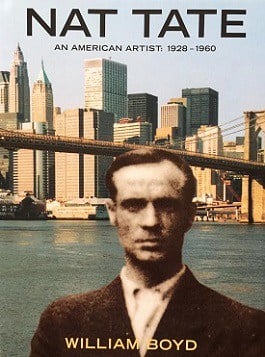

“The great sadness of this quiet and moving monograph is that the artist’s most profound dread – that God will make you an artist but only a mediocre artist – did not in retrospect apply to Nat Tate”.

David Bowie

Nat Tate: An American Artist 1928-1960

In 1998, a small publishing company set up by David Bowie and called 21 Publishing, released the biography of a little-known American Abstract Expressionist as its first project: Nat Tate: An American Artist 1928-1960 by Scottish author William Boyd.

The painter was born in New Jersey in 1928 and, orphaned at the age of 8, he was adopted by a rich couple who lived in Long Island. His adoptive family supported his penchant for the arts, enabling Tate to study painting with Hans Hofmann in Provincetown, Massachusetts, and then to settle in the vibrant Greenwich Village in Manhattan. Tate would soon become an appreciated member of the New York School, though always remaining out of the spotlight.

Tormented and alcoholic, he fell into depression after a trip to Europe in 1959. In France, he met Picasso and Braque and became increasingly unhappy with his work, overwhelmed by these artists’ talent. On his return to New York, Tate managed to either borrow or buy back almost the entirety of his paintings from their owners with the pretext of improving them, but ultimately burning his whole collection. Four days later, on January 12, 1960, Tate ended his life by jumping from the Staten Island ferry as it crossed the Hudson River.

Boyd’s book had a starry launch: Bowie hosted a reception in the studio of American artist Jeff Koons and read extracts from the book to an audience mourning the short, troubled life of the artist and recalling when they had encountered him.

Among the guests were art dealers, collectors as well as artists such as Frank Stella and Julian Schnabel, writers such as Paul Auster, and journalists like David Lister.

It was the latter that grew suspicious and, a week later – just before the British launch of the book – poured cold water on the story unveiling the truth in a piece for The Independent: Nat Tate never existed.

Boyd and his fellow conspirators – namely David Bowie, Picasso’s biographer John Richardson, Gore Vidal, and Karen Wright (then editor of the Modern Painters magazine) – had played the art world one of the biggest pranks.

No others were aware of the scam, not even Jeff Koons, who had hosted the launch on the eve of April Fool’s Day – not a casual date, indeed. Everything surrounding Nat Tate was fictional, from his name, a combination of the National Gallery and the Tate Gallery, to all the pictures documenting his life, which were all part of Boyd’s collection. The reproductions of Tate’s art, on the other hand, the supposed few works left were actually executed by the author who declared: “Nat is my creature; however, a long time ago, he seemed to slip free of my imagination and take on a life of his own”.

Originally intended as a literary exercise, some interpreted the invention of Nat Tate as one of the best-executed pranks, some others as a work of art unto itself, playing with the concepts of fiction and reality. Certainly, it highlighted how hard it is to admit ignorance, especially in glittering circles. As Karen Wright commented, “Part of it was, we were very amused that people kept saying ‘Yes, I’ve heard of him’. There is a willingness not to appear foolish. Critics are too proud for that”. The Emperor has no clothes.

As the prank’s final act, in 2011 a painting entitled Bridge no. 114 and signed by ‘Nat Tate’ – though actually created by Boyd himself – was auctioned at Sotheby’s in London and sold for £7,250 to benefit the Artists’ General Benevolent Institution.

Relevant sources to learn more

The Sneakiest Show In Town

T.I.C.A – Tirana Institute of Contemporary Art

Nat Tate: my part in his art. William Boyd explains the origins of his fictional artist, Nat Tate, and why one of ‘his’ paintings is going on sale.