Exhibitions and Fairs

Berlin’s Beloved Berghain Transforms into Contemporary Art Space

By Shira Wolfe

“All over the world, Berghain is known as the ultimate place of freedom.” – Christian Boros

When the coronavirus hit Berlin in March 2020, it meant an immediate end to the German capital’s party scene. Overnight, clubs like Berghain, Berlin’s most famous techno temple known for its tough door policy and open and inclusive nature once you make it inside, were closed for the unforeseeable future. At the same time, the art world was one of the hardest-hit sectors. Exhibitions and art fairs were cancelled, travel was restricted, and artists suddenly faced serious difficulties showing their work.

Somewhere in the first few months of the pandemic, Berlin art collector Christian Boros wrote to Berlin’s culture senator Klaus Lederer, suggesting they talk. Together, Christian and Karen Boros run the Boros Foundation, presenting their contemporary art collection to the public in a former World War II bunker in Berlin. In fact, the Boroses had been approached by the owners of Berghain, Michael Teufele and Norbert Thormann, with the suggestion of a collaboration. What resulted was Studio Berlin, an exhibition of 117 Berlin-based international artists organised and curated by Karen and Christian Boros and Juliet Kothe (director of the Boros Foundation) at Berghain.

In keeping with the spirit of Berghain, photography is strictly forbidden. Not even the artists themselves are allowed to take pictures of their art in the space. As explained by Juliet Kothe and Karen Boros, this means that for once, people will have to try to put into words to each other what they’ve seen, instead of simply showing each other a few photographs.

Studio Berlin at Berghain

Entering Berghain, the space suddenly feels a lot smaller without the countless bodies packed together – proving how much space there really is here. But that impression quickly fades away as the artworks, located all over Berghain, even in the toilets, interact with and articulate the space in a new way.

Julius von Bismarck is responsible for such large-scale undertakings as his lightning-taming project, initiated after he was struck by lightning while camping in his car in the wilderness. For Studio Berlin, the artist hung a high-sea buoy (Die Mimik der Tethys, 2019) from the ceiling of the main dance area. The object bobs slowly and rhythmically up and down between this space and the Saüle dance floor below, to music playing from Berghain’s Funktion-One speakers. This object, which is far away from its natural context of the sea, somehow seems perfectly at home here, akin to one of the many rhythmically writhing bodies that have left their traces in this space.

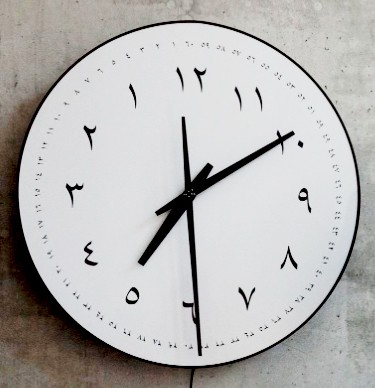

Instead of the stage, there now hangs a giant clock with Hindu-Arabic numerals by Khaled Barakeh – One Hour is Sixty Minutes and Vice Versa (2009). Semitic languages are read from right to left, and so this clock ticks counterclockwise, playing with the conception of norms and directions embedded in our language and culture and suggesting a fluidity between cultures. Ironically, this large clock seems to be telling us the time in a place where ordinarily, time ceases to exist and hours could turn to days. Nearby, also on the wall where the stage used to be, hangs a painting by Andro Wekua, a portrait of a seated man hovering, waiting, in a world of blue.

In the bar area, the famous Berghain bouncer-and-photographer Sven Marquardt’s photos are on display, projected as a slideshow. Below, Viron Erol Vert’s sculptural meat slices really drive the message home that there won’t be any drinks served in this bar for a while. Klara Lidén’s water canister, converted into a lamp, echoes the temporary new use of Berghain – converting something with an existing history and meaning into something new.

Even the toilets are populated by artistic interventions. In one, Berghain resident DJ Sam Barker’s self-playing piano brings unexpectedly delicate music into the club, while in the other toilet space, Cyprien Gaillard created a difficult-to-spot permanent piece by engraving three figures sleeping it off beneath a tree into the stainless steel toilet wall. The piece is his version of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s The Land of Cockaigne (1567), which he renamed The Land of Cocaine.

In Panorama Bar, Petrit Halilaj and Alvaro Urbano’s giant flower hovering over the empty DJ booth is their nostalgic testament to how they met and fell in love there. Elsewhere, Jeremy Shaw’s photograph of an evangelical church scene complete with priest and woman in a state of rapture and trance is fragmented and distorted by the prism he placed in front of it. Though it could be a bit of a cliché to compare evangelical rituals with drugged-up partying and ecstasy, this bizarre black-and-white scene works as one of the many tiny universes within Berghain.

Some artists even went as far as to create their own special rooms and environments within Berghain. There’s Thomas Zipp’s installation in the hallway complete with wallpaper, chairs, a little coffee table, and a painting with a sculpture of a head sticking out – a cozy yet out-of-place scene from the ‘60s in this concrete haven. Up the stairs, on the elevated plateau area with a view of Panorama Bar, Leila Hekmat created an entire outrageous newspaper kiosk, covered in magazine cutouts of Madonnas, pin-ups, horror and porn stills. Quotes like “frenzied tickle” can be found among the images.

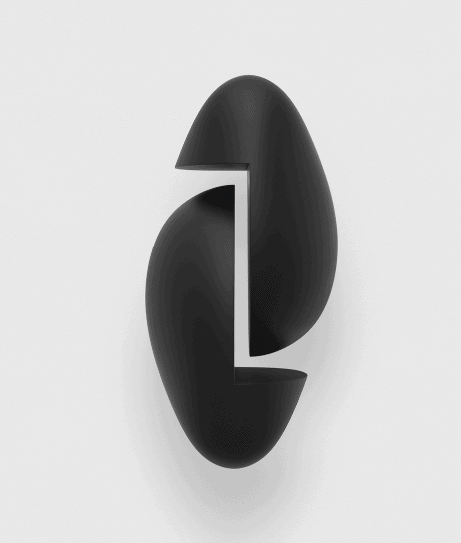

A surprisingly subtle but effective work of sculpture is Iman Issa’s Self-Portrait (Self as Doria Shafik) (2020): two identical black oblong shapes, 3D-printed, come together to create the abstracted shape of a head, but space remains and the objects do not touch. Beside the sculpture hangs a quote from Egyptian poet and feminist Doria Shafik: “Being a woman is absolutely (no) different from being a man.” Sculpture also leads visitors down the stairs to the final part of Studio Berlin, in the large Halle space, which is only open on rare occasions. Julia Phillips’s giant marble teeth are strewn across the floor, down the stairs, as though some absurd version of Hansel and Gretel’s breadcrumbs keeping us from losing our way.

In the Berghain Halle, the artworks are particularly direct in their referencing of these times. There’s the large film projection of a burning fountain, the vulture cast in bronze by Elmgreen&Dragset, and miniature versions of the famous monuments of Europe’s big cities, evoking a disturbing fun park. Olafur Eliasson adds to the experience with his mirror installation, creating an infinity mirror situation that allows people to look at themselves for the first time in Berghain. There are no mirrors in any part of the club, not even the toilets.

Studio Berlin at Berghain will be open until the end of the year. Tickets can be booked through the Studio Berlin website, either for a guided tour (led by Berghain and Boros Foundation employees) or an open house where you can explore at your own pace. Studio Berlin is an excellent example of the wide-ranging possibilities for art and community when important cultural actors and institutions combine their experience and resources. It’s also a wonderful opportunity to reconnect with one of Berlin’s most beloved and unique spaces.