Articles and Features

What Can Contemporary Caribbean Art Teach Us About Diaspora and Identity?

Anthony Dexter Giannelli

Defying singularity, the dynamic nature of the Caribbean region builds upon historical layers of conflicting and converging peoples and cultures. Through violent colonial and neo-colonial conquests, the overlay of stories and perspectives provokes any who attempts to understand identity in a simplified way. Contemporary Caribbean art pulls from the workings of Caribbean artists at home and in diaspora across some of their former and even current colonial powers. Like African diaspora art reflects on the brutality of colonialism and its legacies and celebrates Black culture around the world, contemporary Caribbean art expresses the twofold nature of diasporic identities as well as the rich and diverse experiences of the various diasporic cultures in different metropolitan centers.

Caribbean art and its diaspora

A legacy of colonialism, the Caribbean diaspora has created an environment that transcends singular definitions of shared cultural identities. Today, thanks to the growing change in attitudes and interest in their identity and stories of their own, diasporic voices are growing louder across the art world, helping us to transcend former colonial divisions that have dictated understanding of the region, and to address wider issues.

Recently, several museums in centers with large Caribbean populations outside of the region have highlighted artists of the diaspora focusing not only on Latin and Afro-Caribbean art but incorporating the dialogue and interchange that the former colonies have had on their artists at home.

Colonial Legacies

During the colonial era, the Caribbean region was split mainly between Spain, England, and France, similarly to the rest of the Americas. However, the Caribbean in particular saw a greater Dutch colonial presence and even the inclusion of smaller European nations such as Denmark. Even though many Caribbean nations gained independence in the 20th century, the region went through several transitional eras with a resurgence in colonial presence from their northern neighbor, the United States, and remains one of the few regions in the world still with colonial territories. Peoples from the Caribbean make up some of the largest populations of diasporic peoples today both within the region itself and in the global north. In this context, maintaining or building an identity when displaced on the third level becomes increasingly complex.

Shaping Identities

Because of this history, the common understanding of Caribbean identity can vary greatly depending on geography. To the average Londoner, the word ‘Caribbean’ may mostly mean African descendants of the former British colonies such as Jamaica, who have immigrated to the UK, while in New York – although there is a substantial population from English speaking Caribbean populations such as the Bahamas, Trinidad & Tobago and the US Virgin Islands – there is an enormous population from the Spanish speaking Caribbean, mainly the Dominican Republic and current US territory Puerto Rico. In Toronto, the Caribbean community reflects the wildly diverse nature of the city and spans the islands and coasts of Central and South American communities. The migration patterns of the Caribbean diaspora reflect the region’s tumultuous colonial history and the people’s long-standing quest for refuge during centuries of violence. The first and second generations of immigrants to northern lands sought explanations and answers to how they defined themselves as both individuals and a community of diverse languages, ethnic backgrounds, histories, oppression or privileges, within their new homes.

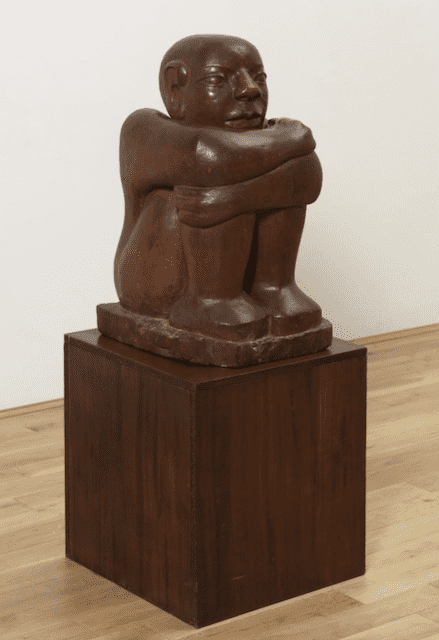

© The estate of Ronald Moody

Contemporary Caribbean art: a history of complexity and plurality

Arguably the most famous of Caribbean artists to come from this diaspora would be the street art master Jean-Michel Basquiat. Born in New York to a Haitian father and a Puerto Rican mother, his works and the enigmatic understanding of his visual language provide a never-ending source of intrigue for the art community. Many of his works present Spanish titles combined with African influences, and his visual lexicon intertwined with his life story provides a small window into the complex environment where artists of Caribbean heritage outside of the islands navigate their identity. Especially within the United States, artists of Spanish-speaking American background are often grouped and interpreted under the umbrella of Latinx art, viewing their identity within the context of ‘latinidad’, a construct that can be excluding or even damaging.

Today, the region is still heavily ruled by these former colonial boundaries, from language to culture, that are all casting their shadows on how peoples from this region build their identity. The graphic visual language of the Cuban Afro-Chinese artist, Wifredo Lam, incorporates influence reflecting this mix, displaying the plurality of cultural mixing in the region. As a Cuban-born artist, “latinidad” often fully embraces his work and identity, while the mixing of East or South Asian with African or Indigenous culture is seen heavily across the Caribbean region not only in its Spanish-speaking islands.

CAM: The Caribbean Artists Movement

The common ground seen across these distant islands was a topic that the Caribbean Artists Movement (CAM) sought to address starting in the 1960s when one of the largest waves of Caribbeans left for the United Kingdom. The diaspora in some cases provided a common ground and opportunity for peoples from isolated areas of the region to exchange ideas in the former colonial mother country to a greater extent than they would have at home. Focusing on the newfound independence and the attention that the former British colonies brought to the region, CAM included all kinds of Caribbean art forms, from literature to visual arts, with the aim to explore common themes of Caribbean identity across mediums.

Institutional Representation of Caribbean Art

In addressing Caribbean art and when serving diverse communities in general, institutions should provide the proper context, one that challenges power dynamics and stereotypes, adding to the overall discovery of different narratives the inclusion of the community.

What we have seen in many cases is the accompaniment of programming with talks, music, and other culturally adjacent discussions surrounding life and identity for the Caribbean Community in their areas. A recent show, Fragments of Epic Memory, which opened this autumn at the Art Gallery of Ontario, and Life Between Islands – Caribbean British Art 1950s to Now to open this winter at the Tate Modern in London, are featuring works from Caribbean-based artists and artists of the diaspora, making commentary on the interchange and influence between the communities. In particular, the Tate modern is going to include recent works of popular British-born artists tapping into Caribbean visual culture, including popular white artists such as Peter Doig. It will be interesting to see how the museum will choose to contextualize the white British artists shown along with those of Afro Caribbean background, ultimately exploring the diversity of Caribbean identity and challenging our perceptions as a whole

Looking to the future

Now, as we welcome the onset of third or fourth-generation diasporic communities – for all that divides the peoples of the region at home begins to fade – expressing identity with visual practices becomes more and more varied, complex, and abstract in the most beautiful ways, less defined by colonial borders. Thanks to connections made by preceding artists and groups such as the Caribbean Artists Movement, new generations of artists are able to connect and form identities in ways that may not have happened in the islands alone, and we hope to see this nuanced view of the region represented within the cultural institutions that serve these communities.

In closing, a recent phenomenon has been recently challenging our understanding of cultural development. Think of one of the most celebrated and popular musical styles from Mexico to Chile and beyond: the beloved oh-so-Latin genre of reggaeton: it was created by a mix of English and Spanish-speaking Caribbean workers on the Panama Canal music of reggae with Caribbean music such as Bachata and Cumbia. What we sometimes view as separate cultural phenomena still defined by colonial boundaries (Spanish-speaking vs French-speaking vs English-speaking) has more in common than we commonly think. But in for all they have in common, all the recognized legacy mixing of Indigenous, Taino, African, East Asian, European mixes, East Indian, they have so much more in individual, personal stories to tell.