Exhibitions and Fairs · By Shira Wolfe

Chagall, Picasso, Mondrian and Others: Migrant Artists in Paris | Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

With its exhibition Chagall, Picasso, Mondrian and Others: Migrant Artists in Paris, the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam presents the story of these famed artists, alongside lesser-known contemporaries. It is a story of migrant artists in Paris in the first half of the 20th century, an examination of their artistic processes, their breakthroughs, and their struggles as outsiders experiencing both the inspiration of the scene around them as well as polarisation and xenophobia. The exhibition also examines how some of these artists were involved in the fight for decolonisation, a story which is often overlooked when discussing Paris in that period. Finally, the works of groundbreaking female artists of the time, including Natalia Goncharova and Sonia Delaunay, feature in the show. This is also the first time in 63 years that the museum’s large collection of Chagalls is on view: 38 works are exhibited, and an in-depth 5-year research project was held to research 9 iconic Chagall paintings in the collection of the Stedelijk Museum.

“Migration offers a perspective that opens a door to new ways of looking at art. What brought these artists to Paris, what did they find there, and what did they take away with them? How did they find their way, how were they treated, and what led to their success?” – Stedelijk Museum

Radical Modernism: Picasso, Braque, van Dongen

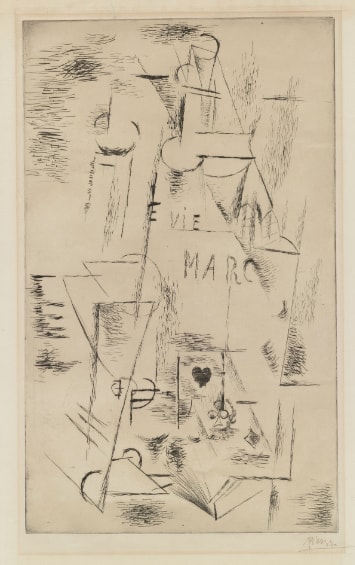

The exhibition takes off with the radical modernism of Pablo Picasso and Kees van Dongen, who both found artist studios in Montmartre in the early 1900s. Both artists started painting what they saw around them: prostitutes, street performers, and poor people in the neighbourhood. They also realised that in order to stand out, they had to be bold. A shift towards a radical modernism soon took place, with Van Dongen’s Fauvism and Picasso’s Cubism. “Glass with Straws” from 1911 is described as one of Picasso’s first revolutionary moments in the development of Cubism. Objects are fragmented or suggested by lines, yet one can still make out the glass with straws. In this same period, Picasso and Georges Braque were engaged in an intensive friendship and artistic exchange. Their deep creative connection is reflected in the two artists’ still lives – Picasso’s “Still Life with Bottle of Marc” (1911) and Braque’s “Fox” (1911) hang in the same gallery and closely resemble each other in style and execution.

One of the key pieces in the gallery is Jan Sluyters’ “Bal Tabarin” (1907), a wild pointillist romp of a painting depicting party-goers dancing beneath a canopy of explosive lights. Robert Delaunay’s “Formes Circulaires. Soleil, Lune” (1912-1913) offers another welcome colourful addition to the often somber colours of Cubism.

Universalism: Piet Mondrian

In 1911, Piet Mondrian visited the Picasso/Braque exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum. This was the first ever museum presentation of Cubism. Mondrian moved to Paris, enamoured with its avant-garde tendencies. But instead of following in the footsteps of Picasso and Braque, he found himself more drawn to the art of Le Fauconnier and Léger in order to express his universalist spiritual tendencies. In the Mondrian paintings in the exhibition, we see how his works take the visible reality as their starting point. In “Composition no. XV” (1913), for example, the iron structure of a signal bridge of the Gare Montparnasse can still be recognised. Other artists who started working in Mondrian’s pure, abstract, primary-colour style are also shown in the exhibition. A César Domela canvas, “Composition neo-plastique no. 5 E (1924-1925), precisely copies Mondrian’s primary-colour compositions.

Modernism and the Homeland: Joaquín Torres-García

A fascinating contribution to this overview of avant-garde Paris in the first half of the 20th century comes from the Uruguayan artist Joaquín Torres-García. Torres-García met Theo van Doesburg and Piet Mondrian in Paris in 1928, where they connected over art’s universal power of expression. For Torres-García, the origins of abstract art lay in Pre-Colombian art. He believed that there are structures and symbols with a universal meaning, as old as humanity itself, which communicate at an intuitive level. Torres-García’s abstract works contain pictograms like the sun, people, and a boat, while at the same time experimenting with blocks of colour characteristic of De Stijl. Works by the Cuban-Chinese Surrealist Wilfredo Lam, and Mexican Diego Rivera, similarly show an engagement with the international avant-garde in Paris on their own cultural heritage terms.

Chagall in Paris: Jewish Identity and Homesickness for the Old Country

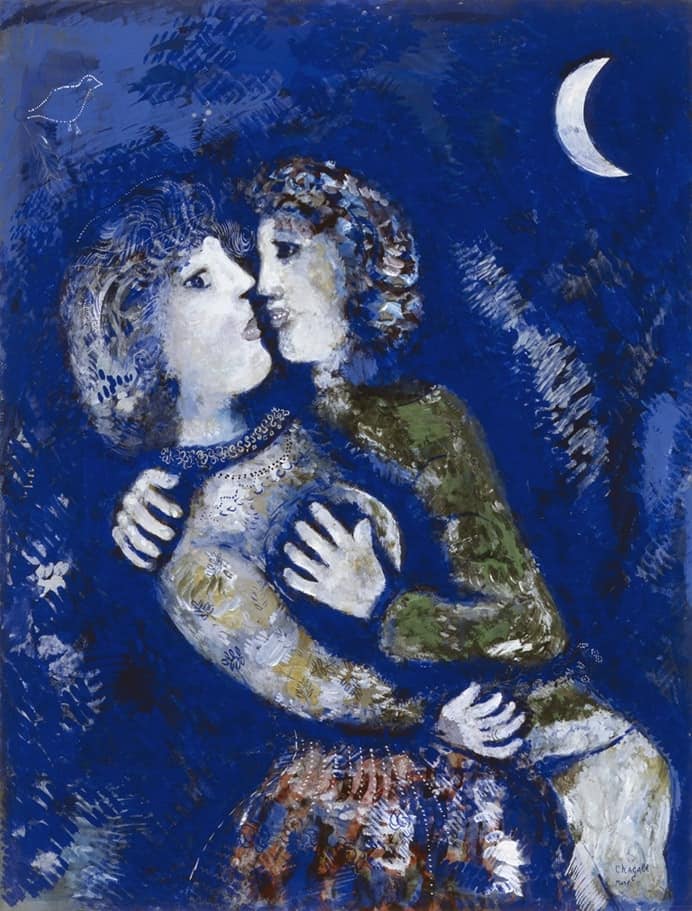

One of the highlights of the exhibition is the collection of Chagall paintings and lithographies. Tracing his development in Paris, we can see how he painted different themes in different periods, influenced by the atmosphere around him. Many of his paintings contain elements referring to his Russian-Jewish heritage and his homesickness. In a striking portrait of his first wife Bella, “Bella in Green” (1934-1935), we see this longing for their home country reflected in Bella’s tragic, emotional gaze. After the First World War, Chagall painted according to the prevailing norm of control and order and also sought to connect to the French tastes by painting the universal theme of love. From 1933, as Anti-Semitism was on the rise, Chagall often emphasised his Jewishness by painting Jewish subjects like synagogues and rabbis.

“Who am I? Who are we? What are we in this white world?”

Aimé Césaire

Colonialism and Artists’ Responses

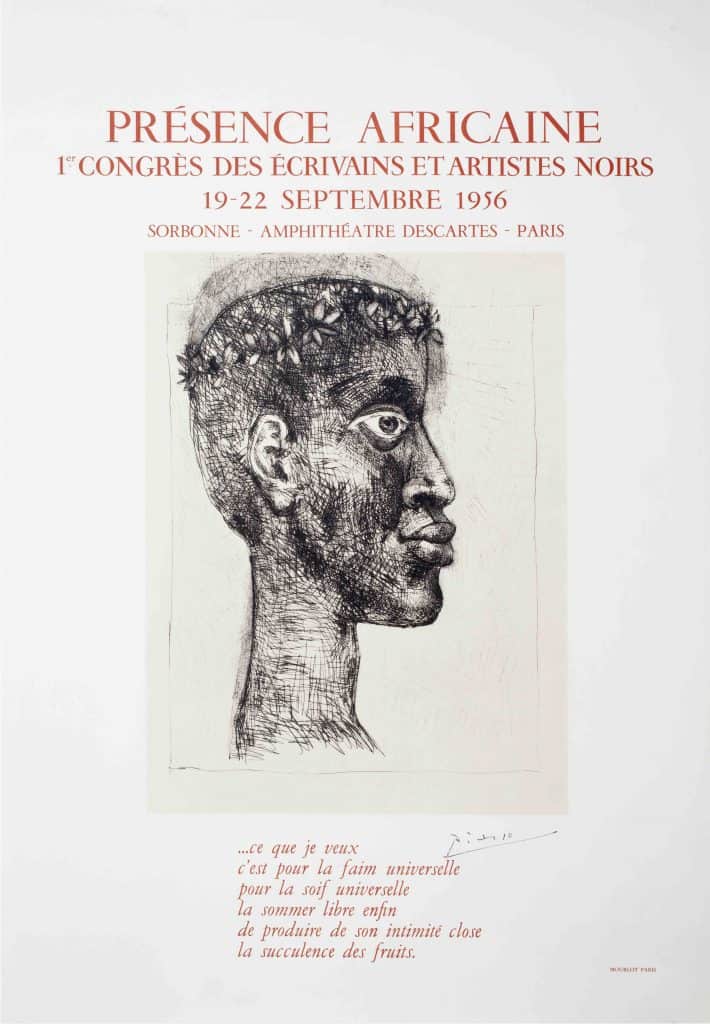

During the First World War, thousands of colonial soldiers of Algerian, Moroccan, Tunisian, Senegalese, Vietnamese and French Antillean descent were sent to war. Approximately 80.000-85.000 of them were were killed or went missing. Photographs show these soldiers in Paris, soldiers who have often been forgotten about in the stories told by mainstream history. Furthermore, the exhibition examines the work of influential Afro-Caribbean writers and poets like Aimé Césaire, Alioune Diop and Leopold Senghor, who combined pre-colonial traditions with modernist tendencies of alienation, fragmentation and experimentation. Attention is given to Présence Africaine, the journal founded by Alioune Diop in 1947 and published in Paris, which was at the forefront of the decolonisation struggle of former French colonies. Picasso made the cover drawing of the 1956 edition of Présence Africaine.

Lesser-known Artists With Stellar Works

Chagall, Picasso, Mondrian and Others: Migrant Artists in Paris gives space to lesser-known artists whose works hold up brilliantly next to those of the more famous names of the time. Mommie Schwarz’s dark vision of Paris, Sonia Delaunay’s use of curtain fabric for her painting, the 16-year-old Baya’s “Woman in a Green-Flowered Dress, Houses and Trees” (1947), Ossip Zadkine’s stunning sculptures, Marlow Moss’ De Stijl-inspired works, and the brilliant abstractions of the Dutch artist Nicolaas Warb (a pseudonym of Sophie Warburg); all of these leave an impression and invite further research into the oeuvres of these artists who made up an entire generation of avant-gardists criss-crossing through Paris in the first half of the 20th century.

An excellent and compelling overview that should not be missed. Runs through 2 February 2020.