Articles and Features

Charles Pollock, ETC galerie d’art, Paris

In the annals of art history, indeed of history generally, the name of Pollock is a well known one, needing almost no introduction as the maverick innovator of drip painting. He was the original action painter—to borrow the phrase coined by Harold Rosenberg in 1952 and memorialised forever in Hans Namuth’s footage—immortalised not only by the animated canvases for which he is famed, but also by the mythology that surrounds his life and work, and most likely accelerated into an iconic posterity by a dramatic, untimely death. What is much less known is that Jackson was not the only Pollock, nor the only successful artist within his immediate family and that his elder brother Charles was in fact the trailblazer who set the example for the younger, more celebrated sibling to follow. Whilst one could readily check the boxes marked depression-era Works Progress Administration muralist and celebrated abstract expressionist for Jackson, this trajectory applied equally to both Pollock brothers. A new show in Paris, at Galerie ETC shows a group of early mature abstract canvases of the late 1950s and early 1960s by Charles and maps out a clearer territory for his own artistic achievements.

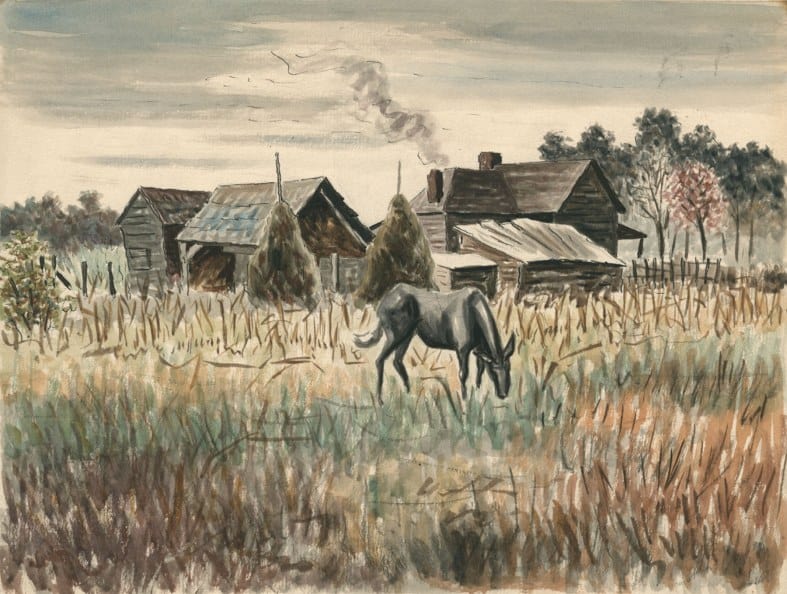

Relocating from the west coast to New York City and the centre of the art scene in the United States in 1926, Charles Pollock’s first act was to enrol at the Art Students League on 57th Street. Also beginning his tenure that year in the teaching faculty was Thomas Hart Benton, the famed social realism muralist and proponent of a folksy style of figurative painting, who, in art historical terms, would come to be equally remembered as Jackson’s mentor. Prior to his move to New York, Charles was already known to Hart Benton, having come into contact with him and his work through their shared interest in the works of the group of prominent Mexican muralists that included Rivera, Siqueros, and Orozco. Once in New York the style of his work became marked by the pronounced influence of Benton’s Regionalist style, also incorporating themes of rural and small-town America, primarily of the midwest and South, into his paintings. He made a living teaching art classes art the City and Country School in Greenwich Village, where he also managed to secure work for Jackson as a janitor.

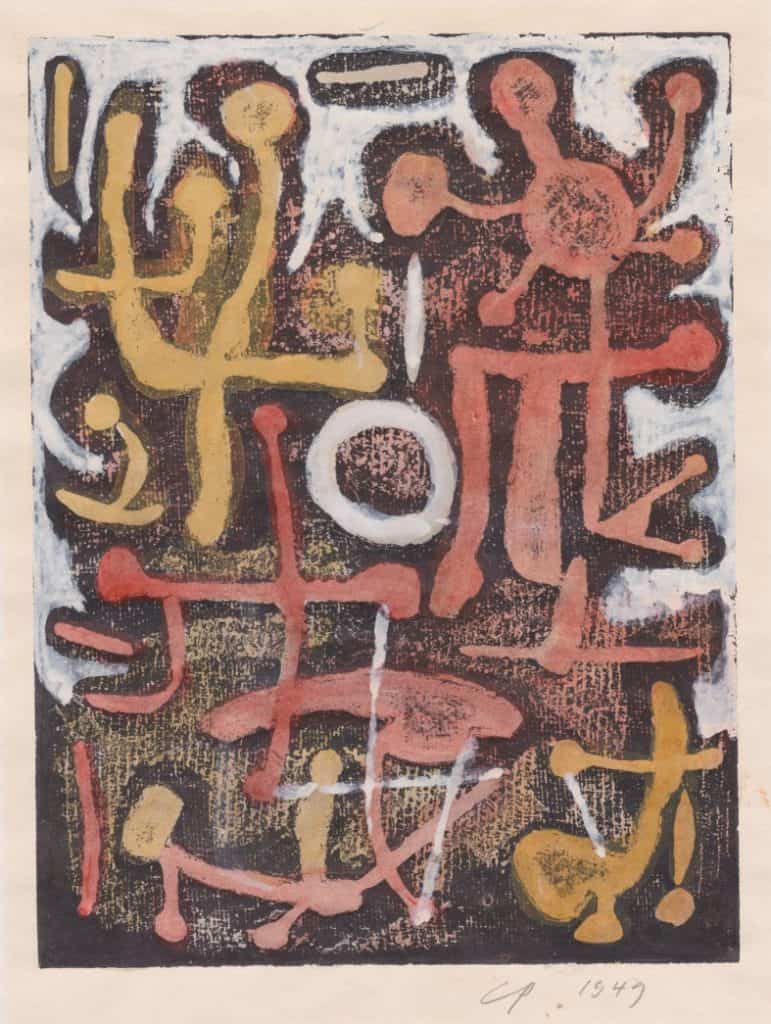

During the 1940s Charles began turning his practice increasingly toward abstraction, feeling that documenting the lives of farmers, workers and ordinary Americans in the dust belt was a job better left to photographers like Walker Evans. His first forays into abstraction experimented with the amorphous forms of post-Surrealism one associates with many of the artists of the New York School of this period. Charles’ works from this time certainly sit comfortably alongside contemporaneous examples by his peers and they were accepted and well regarded by critics and collectors of the day. 1956 might have been a turning point for the elder Pollock. He had sequestered himself for a year in Mexico, working in relative isolation on the shores of Lake Chapala, creating strong work that he was pleased with and that was beginning to garner attention. However, that year also witnessed the death of Jackson in a drunken car smash, a seismic event that not only caused deep sadness on a personal level, but also catapulted the focus onto his younger brother’s work in ways that could not have been anticipated. The accident precipitated a critical resurrection of the younger Pollock’s work, whose reputational lustre had begun to wear thin in the immediately preceding years. Moreover, during the years of overlap of their respective New York careers Charles had always been considered the more reticent—too diffident to put himself forward and not adroit at playing the necessary games needed to smoothly navigate the political and social minefields of New York’s burgeoning art scene. However, the year after Jackson’s death, Charles did meet Clement Greenberg, the critical titan who had once been the biggest champion of all of his younger brother’s work, even before others were prepared to take it seriously at all. Their friendship lasted a decade and coincided with the rise to maturity of Charles’ first significant phase of abstraction.

“History is both fickle and selective, and the criteria for inclusion is often just as much success related as it is qualitative. Charles Pollock’s case is a bit different.”

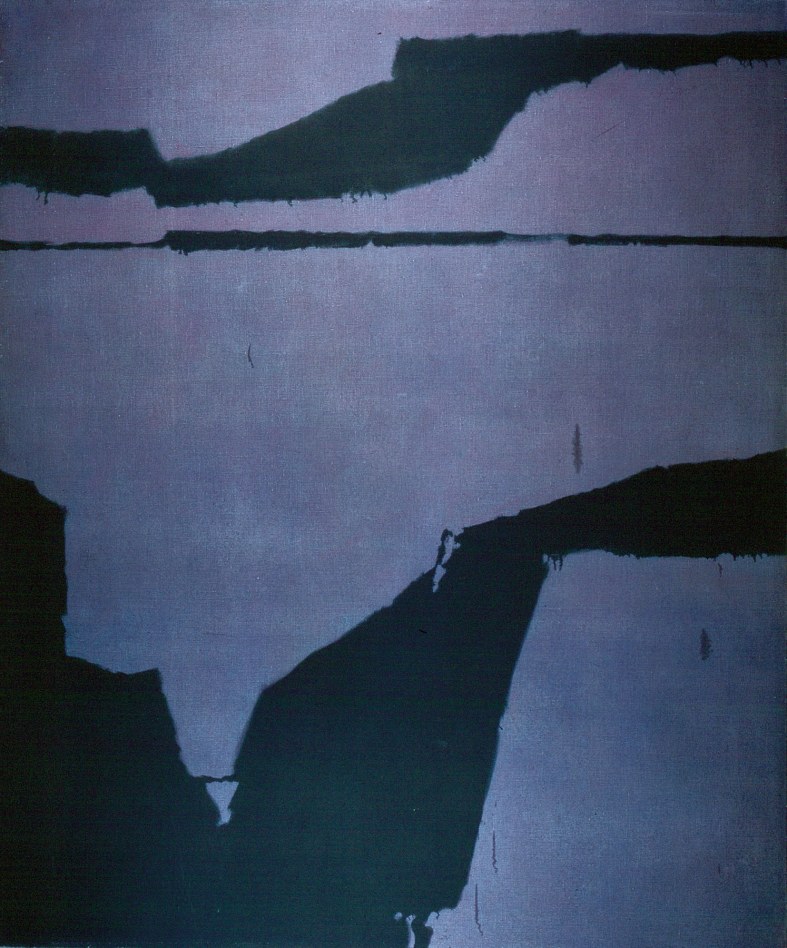

The exhibition at ETC arrays nine such canvases, of the kind of largeish scale that began the debate as to whether a work could still be called an ‘easel’ painting, or whether it could be liberated from the constraints of the bourgeois interior it used to have to respect and serve in order to justify itself. This was an era in which painting needed no justification, save the freedom to explore its own means and ends. The works on display evince all the formal qualities that enabled Greenberg to supply a sincere and supportive admiration. Executed in tones of rich, evenly applied deep color, against which are set more jagged black elements with furred edges, the canvases on display show a sustained and impressive consistency. One might describe them as somehow bridging the gap between the more stridently expressive nature of the first generation of abstract expressionists, characterised by the slashing gestural brushstroke and abandonment of restraint, and the Color Field painters of the very late 1950s and 1960s, whose work essayed more sober expressions of plane and color. In fact, rather than echo the kind of internal energy one discerns in the work of Jackson Pollock and, to a different extent, Willem de Kooning, the works have greater visual affinity with paintings of the period by Robert Motherwell and Clyfford Still. They are also imbued with a certain Japonist feel, perhaps a result of Charles’ lifelong interest in, and mastery of, calligraphy. The works possess an elemental monumentality that implies an extension beyond the confines of the painting’s edges—arbitrary limits that barely contain the overall sense of scale, heft and weight the works convey. It would be easy to argue that the sublime as a subject was also of interest here. The depth of field is rich and sumptuous and in fact closely allied to the color fields of Louis and Noland—rather than paint on the surface, these works embody the color field pursuit of paint as surface. Pigment is soaked into unprimed cotton duck, merging color and support into one and eschewing the expressive texture of the brushstroke.

Art history usually has very little to say about those artists who display a certain level of competence, but who somehow failed to make their mark in any kind of seminal way. Despite the sincerity of their dedication they achieve neither fame nor acclaim. History is both fickle and selective, and the criteria for inclusion is often just as much success related as it is qualitative. Charles Pollock’s case is a bit different. History has a fair amount to say about him, but most often within the wider narrative that accompanied his younger brother, despite an accomplished half-century career of his own that encompassed an impressive evolution of style and a highly respected stint as a professor of various artistic disciplines. His own inclusion in the history books might sadly be described as a footnote, asterisked with the caveats of his relationship to Jackson and stoic quietude when set against the maelstrom of his brother’s tale. But there is another story there, buried within this, one of genuine quality and a painterly talent that did realise works of rare gravitas. The exhibition at ETC proves that whilst the work conforms to the kind of painterly agenda Greenberg considered the purest and worthiest of all, it is executed with an authenticity and reductive mastery of color that marks the author of it as no acolyte or maker of pastiche, but a voice of original and quiet power that just got a little lost in the noise.

Relevant sources to learn more

ETC Gallery Website

Charles Pollock Archives

ETC Galerie profile on Artland

Alex Da Corte | Marigolds, Karma, New York