Articles and Features

Fauvism: The Art Style That Liberated Colors

By Adam Hencz

“When I put a green, it is not grass. When I put a blue, it is not the sky.”

Henri Matisse

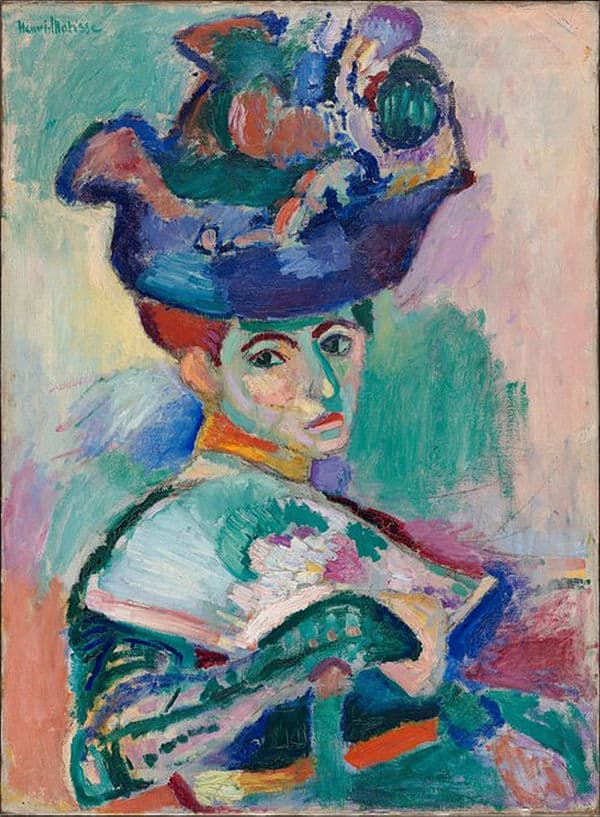

Fauvism was one of the early-twentieth-century art styles and consisted of like-minded artists who were initially ridiculed and called Les Fauves, meaning “the savages” or “the wild beasts” in French. It was modernist art critic Louis Vauxcelles who first dubbed them after he saw the radical paintings by Henri Matisse, André Derain, and Maurice de Vlaminck at the 1905 Salon d’Automne exhibition in Paris. Fauvism would mark the beginning of the twentieth-century artistic avant-garde. The revolutionary style involved using highly saturated colors juxtaposed in flat areas. The emotional charge of Fauvist portraits and landscapes brought the possibilities of color in art to the forefront, as the style became a major influence on future art movements like Expressionism.

What is Fauvism?

The term ‘Fauvism’ refers to a novel style in painting that characterized the works of a closed circle of French artists that was primarily structured around Henri Matisse, but also indirectly influenced other artists like Raoul Dufy, Georges Braque, or Georges Rouault. A short-lived trend that grew out of Impressionism between 1905 and 1908, Fauvism preferred a simpler and less naturalistic form of expression. The genre’s followers adopted an expressive emotionalism that emphasized the artist’s inner feelings and ideas with the intricate arrangement of cold and warm colors and the creation of decorative compositions. Fauvism is not technically a movement – as there were no written guidelines or manifestos, no membership entries, and no exclusive group exhibitions – but is rather a periodization.

Fauvism and colour theory

Fauvist artists broke away from traditional impressionist methods and innovatively experimented with exaggerated colors, composing their paintings based on wild color contrasts. The fauvists favored pairing complementary colors, like purple and yellow, magenta and green, or orange and blue. These colors are on opposite sides of the color wheel and were often picked for the main color palette of fauvist paintings as well as used at high saturations. However, fauvist artists did not choose colors based on scientific theory as the post-impressionists did, but on feeling, observation, and the nature of each chromatic experience. The Fauves used color radically, advocated for liberating color from realistic depiction assigning emotionally charged meanings to it instead.

Courtesy San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Style and characteristics

The Fauves rejected optical realism created by Impressionism such as realistic portrayals, and did not apply perspective, or use light-shadow effects. The spontaneous and subjective responses to the subjects in their artworks were expressed through broken brushstrokes and bright colors, using paint straight from the tube. Fauvist artists shifted away from urban themes and returned to subjects such as country landscapes, leisure scenes, or portraits. Fauve paintings are characterized by impulsive lines, spontaneous compositions, and a simplified drawing technique.

Most famous Fauvist paintings

The most famous fauvist artworks were created by three of the major exponents of Fauvism, namely Henri Matisse, André Derain, and Maurice de Vlaminck.

The Joy of Life by Henri Matisse

After the turn of the century, inspired by Cézanne, Matisse started experimenting with color as the motive of his creations. Matisse painted many landscapes during the summers he spent in Southern France. One of them, entitled The Joy of Life (1905), depicts an idyllic and imaginary scene with bright and cheerful colors. One remarkable element in this painting is the group of dancing figures that resembles a group of figures on one of Matisse’s later paintings, The Dance (1909). He used several independent motifs and brought them together into an allegorical composition, displaying pastoral simplicity and happiness. His work is appreciated as a much-needed sign of peace and hope during darker times.

Charing Cross Bridge by André Derain

Co-founder of Fauvism, André Derain attended the Carrière Académie from 1898, where he was a peer of Henri Matisse. Derain rented a flat in Chatou with Maurice de Vlaminck, whose desire to make color the primary element of expression permeated him and his work for years. In 1905, he worked with Matisse at Collioure and arrived at a harmoniously decorative depiction of landscape. He experimented with colors that melt into large surfaces surrounded by definite contours, a technique he applied to his version of the Charing Cross Bridge in London. In 1906, the buzz around Fauvism encouraged a French art dealer to commission Derain to create paintings to depict London, a subject that Monet had previously featured. While Monet painted a more sorrowful picture of London’s foggy weather and industrial environment, Derain’s depiction is wild and fiery, but at the same time remains realistic.

The River Seine at Chatou by Maurice de Vlaminck

Alongside his peers Matisse and Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck is considered the third principal figure of Fauvism. His innovative approach to landscape, form, and color helped establish him as a pioneering artist of his era. From the age of sixteen, he lived in Chatou, a small village that is now part of Paris, where the self-taught painter spent much time with his friends Matisse and Derain. In the summer of 1906, he started observing the landscape of his home village differently, as his intuitive application of paint and employing conventional hues became apparent in his paintings like The River Seine at Chatou (1906).

The legacy of Fauvism

Fauvism continues to be regarded as an important period in art history and had a profound influence on many other expressionist movements, including the contemporary Die Brücke and the later Blaue Reiter, and Abstract Expressionism in America. The Fauves’ bold coloration had a formative effect on countless individual artists as well such as Egon Schiele, Max Beckmann, and George Baselitz.

Relevant sources to learn more

Learn more about early-twentieth-century avant-garde movements:

Constructivism

Cubism

Dadaism

Futurism

Surrealism

Suprematism