Articles and Features

Female Iconoclasts – Artemisia Gentileschi

By Shira Wolfe

“She knew Caravaggio as a young girl, her father was an associate of Caravaggio’s, and she really holds her own next to these artists. She’s a really accomplished painter in her own right.” – Letizia Trevis, James and Sarah Sassoon Curator of the Later Italian, Spanish and 17th Century French Paintings, The National Gallery

In this article series, we discuss some of the most boundary-breaking female iconoclasts of our time; women who defied social conventions in order to pursue their passion and contribute their unique vision to society. Last edition featured the German Expressionist artist Paula Modersohn-Becker. This week, we discover the incredible artistic production of Artemisia Gentileschi, the most successful female artist during the 17th century, who worked for the highest echelons of European society, including the English King Charles I, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, and Philip IV of Spain.

Artemisia Gentileschi’s Background

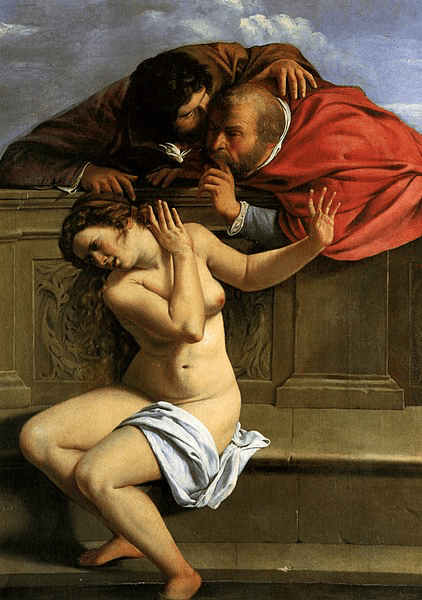

Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1654) was born in Rome, the daughter of Ortazio Gentileschi, an artist who was friends with, and greatly influenced by, Caravaggio, yet developed a softer, more refined version of Caravaggio’s style. Artemisia, the eldest of five children and the only girl, trained under her father, and her earliest signed and dated painting, “Susanna and the Elders,” is from 1610.

When her father realised her great talent, and felt she had advanced beyond the scope of his training, he hired his acquaintance, fellow artist Agostino Tassi, to further her painting education. In 1612, Tassi raped Artemisia, and an infamous trial ensued in which Tassi was found guilty and banished from Rome, but not before Artemisia was tortured in the courtroom in order to confirm that her testimony was true. Tassi received no such treatment.

Artemisia’s reputation was extremely damaged by this event, since people started to gossip about her being a promiscuous woman. Soon after, her father arranged for Artemisia to marry a Florentine painter named Pierantonio di Vincenzo Stiattesi, and they left Rome for Florence. In Florence, Artemisia established herself as an independent artist, often using her paintbrush as a tool to rewrite her stories of trauma and repression. In 1616, she became the first woman to gain membership to the Academy of the Arts of Drawing. She returned to Rome in 1620, and settled in Naples in 1630, where she ran an artist studio until her death.

“What,” wonders Gentileschi, “if women got together? Could we fight back against a world ruled by men?” – Jonathan Jones, The Guardian

The Autobiographical Paintings of Artemisia Gentileschi

Artemisia frequently depicted biblical scenes, and would come to develop a preferred subject matter, namely the depiction of suffering, yet strong women from mythology and the bible. Very often, she worked herself and her experiences into these paintings, creating links between her own struggles to make her way in the rough, dangerous and unfair male-dominated world she lived in, and the struggles of the heroines she painted. Her signature style involved a realistic depiction of the female form, a deep colour palette, and skilled use of light and shadow.

An incredible work is “Judith Slaying Holofernes” (1614-1620), which depicts a scene portrayed by Caravaggio, and many of his followers. But Artemisia’s version does something completely new. Instead of showing Judith cutting off the head of Holofernes, the enemy of the Israelites in the Old Testament, while her maid stands by waiting to collect the severed head, Artemisia’s rendering shows the maid playing an active part in the killing. This creates a portrayal of the scene which is both far more realistic, and also suggests Artemisia’s desire for women to stand together and fight against their male oppressors. In her painting, Judith and her servant press Holofernes down on the bed, pinning him in place while one of them cuts through his throat. His eyes are wide open, caught in this moment of horror, while Judith and her maid continue, a look of unflinching determination painted on their faces.

In a later painting from 1925, “Judith and her Maidservant,” Artemisia returns again to the theme of Judith and Holofernes, this time depicting Judith and her maid moments after the murder, while they place the head of Holofernes in a bag. Here, she works masterfully with rich colours, shadows and light, to create a riveting scene of the two women dealing with the aftermath of their actions.

Between 1623-1625, she painted “Lucretia,” her rendition of the story of the Roman noblewoman Lucretia who committed suicide after she was brutally raped by Sextus Tarquinius, the son of an Etruscan king. In Artemisia’s painting, we see Lucretia in the moment just before she resolves to kill herself. Again, she chooses to depict her heroine as a strong, self-determined figure.

Artemisia’s Self-Portraits

Aside from these powerful portrayals of female heroines, through which she brilliantly interwove her own stories and feelings, Artemisia Gentileschi also created several actual self-portraits. Her “Self-Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria” (ca. 1616) depicts Artemisia as Catherine, who was tortured by being tied to a wheel with metal spikes, after winning a debate from 50 of the emperor’s best philosophers. The painting shows a quiet resilience as she holds the instrument of her torture.

One of her most celebrated self-portraits is “Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting,” completed in 1639 at the British court of Charles I, who had invited her to London to work for him. Holding a paintbrush in one hand, a palette in the other, she identifies herself as the female personification of painting.

Armed with her paintbrush, Artemisia Gentileschi shaped her own identity, her own empowerment, and her own life, a remarkable feat for any woman living in her time.

Relevant sources to learn more

From 4 April to 26 July 2020, the first major exhibition of the works of Artemisia Gentileschi in the UK will be on view at The National Gallery in London. The exhibition, titled “Artemisia,” will bring together approximately 35 works from various public and private collections around the world.

For more interesting insights into the life and work of Artemisia Gentileschi, check out: