Articles & Features

Female Iconoclasts: Beverly Pepper

“Other women want diamonds and fur coats. I just want to live in a factory”.

Beverly Pepper

In our article series “Female Iconoclasts”, we celebrate women artists who are among the most innovative creators of our time; women who sometimes defied prevailing social conventions to pursue their passion and contribute their unique vision to society. This week we feature the trailblazing work of American sculptor Beverly Pepper, an ambitious and courageous spirit who created a unique sculptural language synthesising classicism and modernity, roughness and elegance, monumentality and essential shapes. Standing out in a male-dominated field, Pepper realised physically demanding as well as technically advanced works, ultimately offering a new perspective on mid-century sculpture.

“The abstract language of form that I have chosen has become a way to explore an interior life of feeling… I wish to make an object that has a powerful presence, but is at the same time inwardly turned, seeming capable of intense self-absorption”.

Beverly Pepper

Education and early works

Beverly Pepper (née Stoll) was born on December 20, 1922, in Brooklyn, New York City to middle-class parents of European origins. Though they were not particularly drawn to Fine Arts – her father was a carpet seller and a furrier, whereas her mother was a volunteer for the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People – her destiny seemed to be written from the beginning: she would become an artist. The story goes that at six years old, amidst the Great Depression, Beverly sneaked a dollar from her mother’s purse and went to the local candy store; among sweets and treats of any kind, she spotted a three-drawer coloured pencil box: it was love at first sight. On that occasion, the mischief cost her a good beating from her father’s hand but also infused her with passion and determination that would never fail thereafter.

Already captivated by geometry and construction, Pepper decided to pursue an engineering academic path but the chauvinist society of the time got in the way: Engineering, apparently, was no proper subject matter for a woman. Growing up with two strong women as role models – her mother and her paternal grandmother – she had believed to have no limits in her future and had to come to terms with sexism and bigotry at her own expense. In fact, that was only the first one of a string of doors shut in Pepper’s face as her attempt to study industrial design gave the same outcome – being too unfeminine as well. As the ultimate fallback, she graduated in advertising design at the Pratt Institute and the Art Students League in Brooklyn, and, at a young age, she was already a successful – yet miserable – commercial art director in Manhattan.

In the late 1940s, no longer able to bear her job, and with a failed marriage behind her, Beverly decided to start fresh: she moved to Paris, where she studied cooking at the renowned culinary school Le Cordon Bleu and, above all, she studied painting at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière with André Lhote and Fernand Léger. Though never really fulfilled with her creative production, for the next decade she made a career as a respected painter, mostly depicting figurative scenes imbued with social realism as she was struck by the poverty and misery in postwar Europe. The artist travelled around the Old World until she found in Rome the ideal place to grow both artistically and personally: there she held her first solo show at the Galleria Dello Zodiaco in 1952 and also met the man who would become her life’s partner, the American writer Curtis Bill Pepper. The couple immersed themselves in the swinging years of la Dolce Vita and became part of an admired group of American ex-pats – Martha Gellhorn, Ezra Pound, and Norman Mailer among the others – but also other creative personalities such as the director Federico Fellini. Just when it seemed that Beverly Pepper’s career was on the right track, her artistic language was getting close to a radical change.

“Everything in the world slowly converts into iron. It is everywhere, even in a teardrop”.

Beverly Pepper

A change of perspective: turning to sculpture

In 1960, Pepper went on a seven-month trip through America and Asia with her 10-year-old daughter and, after visiting the mid-12th-century Khmer temple at Angkor Wat in Cambodia, everything would no longer be the same. Like an epiphany, the intertwining of banyan trees with the ancient religious monument impressed Pepper’s imagination: it was not only a magnificent example of sculpture and architecture but a total environment, a bridge between past and present. “I walked into Angkor Wat a painter and I left a sculptor”, she remarked a few years later.

As soon as she returned to Italy, Pepper bought a grove of elm trees, carved them into twisting biomorphic shapes, and began exhibiting her new works in Rome.

In 1962, the artist was invited to participate in the exhibition “Sculture Nella Città” (Sculptures in the City) to be held in Spoleto: a handful of major sculptors such as Alexander Calder, Henry Moore, David Smith, and Lucio Fontana would fabricate new pieces in Italian steel factories and locate them around the city. However, there was a condition to join the project: artists were supposed to be able to weld, and Beverly Pepper had never welded in her life. “I was terrified – she recalled – But one thing I learned growing up in Brooklyn is that if you’re offered an opportunity, take it. You don’t have to be qualified. You just have to have the chutzpah to face all the possible downfalls”. Promptly, she got in contact with a local metal foundry and learned to weld, just in time to enter the steel factory in Piombino, Tuscany, where she worked three shifts a day – in spite of those who, many years before, had discouraged her from studying industrial design. Her abstract sculpture The Gift of Icarus still stands in the city to this day.

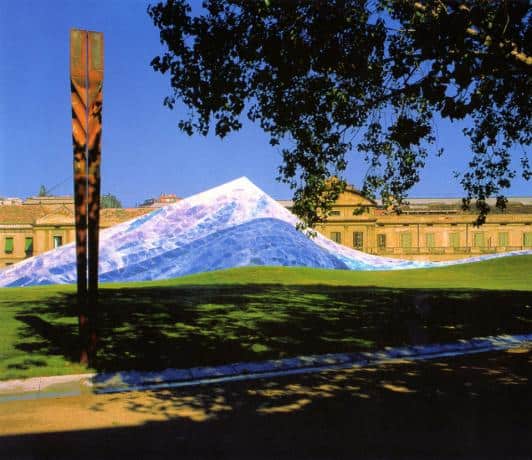

As time passed, Pepper’s sculptures became progressively monumental and minimalistic; metal had become her material of choice as she mastered cast iron, bronze, stainless steel, and, above all, Cor-ten steel – an alloy which develops a stable rust-coloured patina. Her fame grew on both sides of the Atlantic and she realised site specifics installations across the globe: total environments in the intersection between monumental sculpture and land art often incorporating cement, soil, stone, and grass in a perfect combination of natural and industrial materials. Among many others, stand out Amphisculpture in New Jersey, Palingenesis in Zurich, Manhattan Sentinels in New York, and the Hawk Hill Calgary Sentinels.

In 1972, Pepper’s life was at a turning point: she attended the 34th Venice Biennale and moved to the Umbrian city of Todi, a medieval town in central Italy where the artist, along with her husband, restored a 14th-century castle. Living in Umbria, with its serene landscape and sense of stillness had a remarkable impact on her work: “I need the sense of permanence in my life – and Umbria has that quality of history fused into the future.” And for her cherished adopted home-town, Pepper created the iconic Todi columns, four iron giants as spectacular as they were controversial at the time – it was 1979.

Even approaching her centennial, Beverly Pepper continued making art; though she was no longer able to weld or to lift heavy tools, her creative energy never failed. She died in February this year at the age of 97.

Visual language and artistic approach

Critics have often tried to label Pepper’s work. Some have included it in the Land Art production, others have defined it Minimalist and even Constructivist. However, the sculptor always remained independent, developing a transversal artistic vocabulary that proved to be remarkably consistent. At the same time, each one of her projects is strongly linked with her other works as well as with the place it had been conceived for. In fact, one of Pepper’s bigger ability was to capture the genius loci of a particular place and make it visible for everyone to admire, from the density of urban contexts to the remoteness of rural landscapes.

The modernist simplicity of her production transcends time to become classical. The artist often remarked how she intended “for sculptures to bridge time, hopefully holding a measure of those eternal qualities that attract us to the world’s great ageless monuments”. Not surprisingly, her influences were historical, from Trajan’s column and Cleopatra’s obelisk to Bauhaus geometry.

The link with classicism reached the apex with the exhibition at the Ara Pacis Museum in Rome where Pepper displayed her Curvae in Curvae series, organic curvilinear shapes of rust-coulored Cor-Ten that perfectly blended in the Latin monumental site.

Despite its massive character and occasional roughness, Pepper’s work oozes energy and gracefulness and has been often described as “spiritual and “hieratic”.

Recognition and legacy

Today Beverly Pepper is regarded as an acclaimed sculptor. Her work has been displayed and collected by the most prestigious museums, from the Uffizi Gallery to the MET, and her public commissions adorn cities to the four corners of the globe, from Sydney to Houston, from Vilnius to Tokyo, Stockholm, and Jerusalem. However, she is not as well-known as her contemporary peers. Some have argued that living in a small Italian town had kept her on the art world’s periphery, away from the well-deserved fame. Though the artist always rejected these speculations, seeing in the rolling Umbrian hills and the almost mystical peacefulness of Italian countryside her essential source of inspiration.

Arguably, also a generalised chauvinism may have played a role in this. At the time, there were not a lot of women sculptors producing monumental pieces who worked directly in factories and foundries – except for a few other pioneering characters such as Louise Bourgeois and Louise Nevelson – and yet, other male artists’ names always come to mind first. Especially when it comes to Cor-ten, one immediately thinks of Richard Serra, while Beverly Pepper was indeed the first artist ever to experiment with the innovative material in 1964.

Regardless, this did not keep her from being represented by major galleries like the Marlborough Gallery in New York, as well as Kayne Griffin Corcoran in Los Angeles.

In 2019, as the ultimate labour of love for Todi, Pepper designed and donated the city the Beverly Pepper Sculpture Park, an over-five-acres public area comprehensive of twenty sculptures from her private collection ranging from different artistic periods. A contemplative and harmonious dialogue between natural and urban environments, the park stands as a permanent tribute to a life’s work, a unique artistic voice as well as the artist’s love for the Umbrian landscape.

Relevant sources to learn more

An overview of Beverly Pepper’s work

Beverly Pepper Foundation

For previous editions of our “Female Iconoclasts” series, see:

Female Iconoclasts: Yayoi Kusama

Female Iconoclasts: Marlene Dumas

Female Iconoclasts: Louise Bourgeois

Female Iconoclasts: Mona Hatoum