Articles and Features

Female Iconoclasts: The World Through The Lens Of Graciela Iturbide

By Shira Wolfe

“There’s so much Mexico has to offer. There is no need to pursue the American dream. We have our own here, too.” – Graciela Iturbide

Artland’s article series “Female Iconoclasts” celebrates female artists who were among the most boundary-breaking iconoclasts of our time; women who defied social conventions in order to pursue their passion and contribute their unique vision to society. This edition explores the stunning photography of Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide. Iturbide’s career as a photographer spans five decades, and her body of work is fundamental for understanding the development of photography in Mexico and the rest of Latin America. While her photographs can be placed in the realm of documentary photography, she always adds a mysterious or surreal element to the image, revealing the magic in everyday life.

Graciela Iturbide – Towards Photography

Graciela Iturbide was born in Mexico City in 1942, the oldest in a family of 13 children. At the age of 27, she enrolled at the Centro de Estudios Cinematográficos at the Universidad Nacional Autonóma de México to study film directing. During her studies, however, she came into contact with photography through the Mexican modernist master, as well as university professor, Manuel Alvarez Bravo. Iturbide worked as his assistant from 1970-71 and accompanied him on travels throughout Mexico, an experience that truly sparked her love of photography. Iturbide found another mentor-figure in Henri Cartier-Bresson, whom she met on a trip to Europe, finding particular inspiration in the way the French photographer had captured her country’s soul in his Mexican Notebooks. Over the course of five decades, she has developed an incredible body of work presenting intimate studies of Mexicans and indigenous peoples, as well as of other countries and cultures around the world. Every image Iturbide creates evokes a mixture of tradition in a surreal space filled with an unmistakable hint of magic.

Ritual, Life and Death

Iturbide’s work reflects important themes permeating Mexican culture – rituals, life, and death – and is imbued with its spiritual, symbolic imagery, among which the skull stands out as a leitmotiv. For example, in her photograph titled Procession (1984), we see people wearing masks and costumes, and one dressed as a skeleton; while another arresting image, Death Bride (1990), shows a spectral figure in a bridal gown and veil, wearing a skull mask.

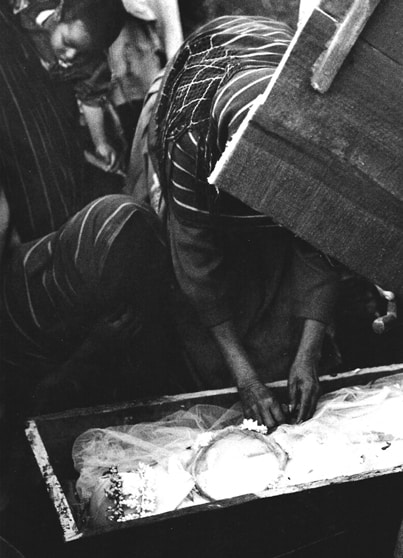

Following the tragic death of her 6-year-old daughter, Iturbide became obsessed with photographing rituals around the death of children, resulting in the depiction of countless angelitos: corpses of children fitted with angel wings before their burial. This practice came to an end when, one day, as she was documenting a funeral, she chanced upon the corpse of a man on the cemetery path, skull and torso picked clean by the birds flocking over in the sky. The artist took this as a sign, as though Death was telling her to stop. And so she did. Iturbide did, however, develop a fascination for birds after this occurrence, to the point that these animals – ambiguously symbolic of both life and death – became a recurrent subject through her body of work.

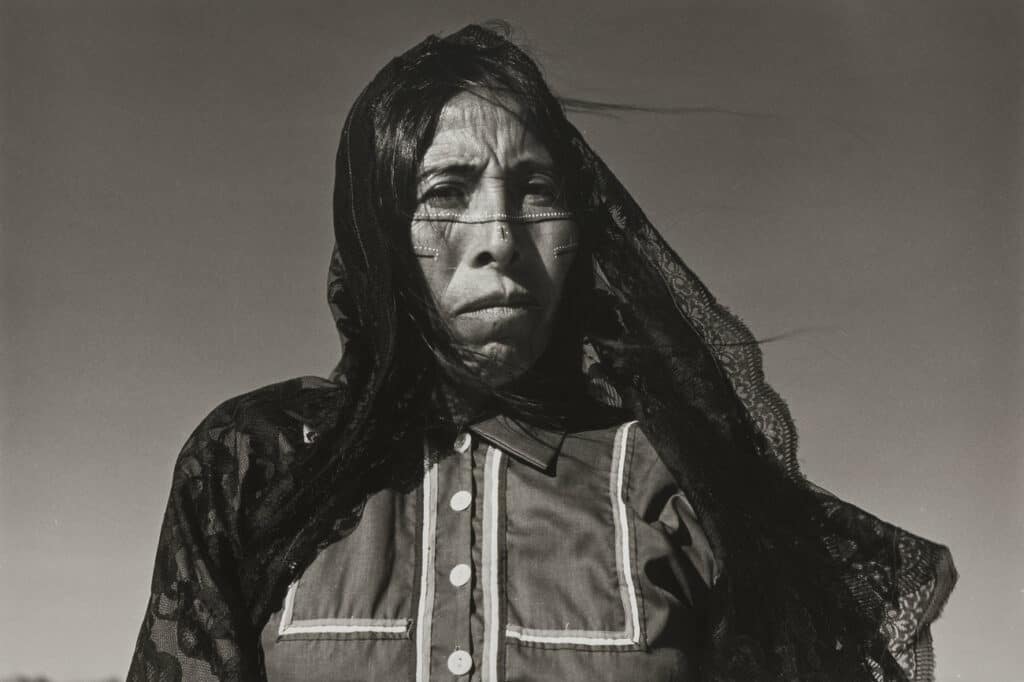

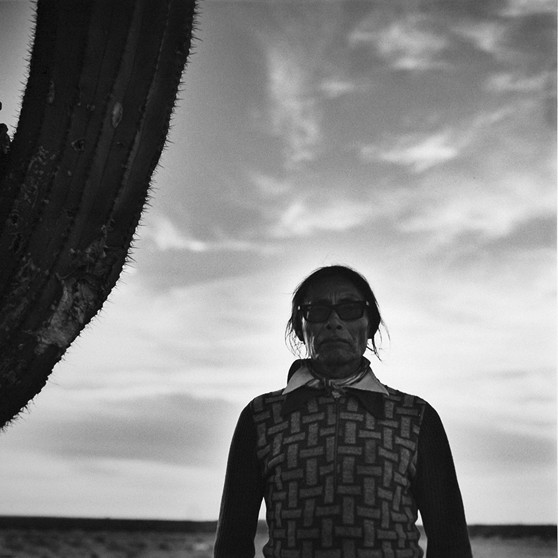

Capturing Indigenous Life – the Seri Indians

When in 1978, the Ethnographic Archive of the National Indigenous Institute of Mexico commissioned Iturbide to photograph Mexico’s indigenous population, she chose to document the way of life of the Seri Indians, a group of fishermen living a nomadic lifestyle in the northwestern Mexican Sonora desert. Through a deeply empathetic approach, she was able to reveal the depth, beauty, and humanity in each individual of this 500-people community. One of her most iconic images of the series is Mujer Ángel (1979), a picture of the back of a young Seri woman in a long dress, who seems to be about to launch herself into flight, her long straight hair flowing down. As Iturbide frequently includes symbols or artefacts in her photographs to create a subtle surprise and set the imagination to work, the woman holds a boombox in her right hand; an element also representing how the Seri Indians have incorporated specific elements of American culture and capitalism in their everyday life, yet without altering their traditions.

“I spent a lot of time at the public market, hanging out with these big, strong politicized, emancipated, wonderful women. It was a mythical place that had been visited by Cartier-Bresson, Eisenstein, Tina Modotti, Frida Kahlo, something I did not know when I was lucky enough to get a call in 1979 from Francisco Toledo who offered me the project.” – Graciela Iturbide

The Role of Women

In 1979, Iturbide was invited to photograph the indigenous Juchitán people, who form part of the Zapotec culture in Oaxaca, southern Mexico. The series, that started in 1979 and runs through 1988, resulted in the book Juchitán de las Mujeres, published in 1989. She focused especially on the marked matriarchal aspects of the Juchitán culture, and was deeply inspired by its strong, determined women. Regarding how she got to know her impressive subjects, Iturbide explained: “I spent a lot of time at the public market, hanging out with these big, strong politicized, emancipated, wonderful women. It was a mythical place that had been visited by Cartier-Bresson, Eisenstein, Tina Modotti, Frida Kahlo, something I did not know when I was lucky enough to get a call in 1979 from Francisco Toledo who offered me the project.” One of the most famous photos from the Juchitán series is Nuestra señora de las iguanas, Juchitán (‘Our Lady of the Iguanas’), an image taken in 1979 and depicting an indigenous Zapotec woman wearing a crown of live iguanas on her head. The photographer met this woman, Zobeida Diáz, at the public market, and managed to capture this incredible image despite the movement of the iguanas on her head. The picture has become so iconic that it is now found in various forms all over Juchitán, and beyond.

Frida Kahlo’s House

In 2005, Iturbide was invited to photograph Frida Kahlo’s house. She was granted one week to take pictures at the legendary Casa Azul, but following her philosophy to only capture things that surprise her, she made sure to create a series of photographs that presented an antidote to the brand Frida Kahlo has become. The series – Iturbide’s only suite in colour – resulted in an intimate representation of Kahlo’s life, simultaneously passionate and melancholy, through the arrangement of her personal effects in her private spaces. The following year, the artist returned once more to Casa Azul to celebrate the reopening of the bathroom, which had been closed up by Diego Rivera in 1954. This time, she took a poetic series of black and white photographs, further offering a tiny window into Kahlo’s raw and complex life – a prosthetic leg leaning against a wall, a dirty bathtub, corsets, and crutches… She ended this series with a re-enactment of Kahlo’s painting of her feet in the bathtub titled What I saw in the Water from 1938.

Graciela Iturbide’s Legacy

Graciela Iturbide continues to live and work in Mexico City, Mexico. She is the recipient of several photography awards, from a Guggenheim Fellowship (1988) to the Hasselblad Foundation Photography Award (2008), and her works can be found in many important museum collections around the world, including the Tate Modern, the Centre Georges Pompidou, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In the words of the Hasselblad Foundation award jury: “Iturbide has extended the concept of documentary photography, to explore the relationships between man and nature, the individual and the cultural, the real and the psychological…[Her photography] is of the highest visual strength and beauty and continues to inspire a younger generation of photographers in Latin America and beyond.”

Relevant sources to learn more

International Center of Photography

For previous editions of our “Female Iconoclasts” series, see:

Barbara Kruger

Sophie Calle

Beverly Pepper