Articles and Features

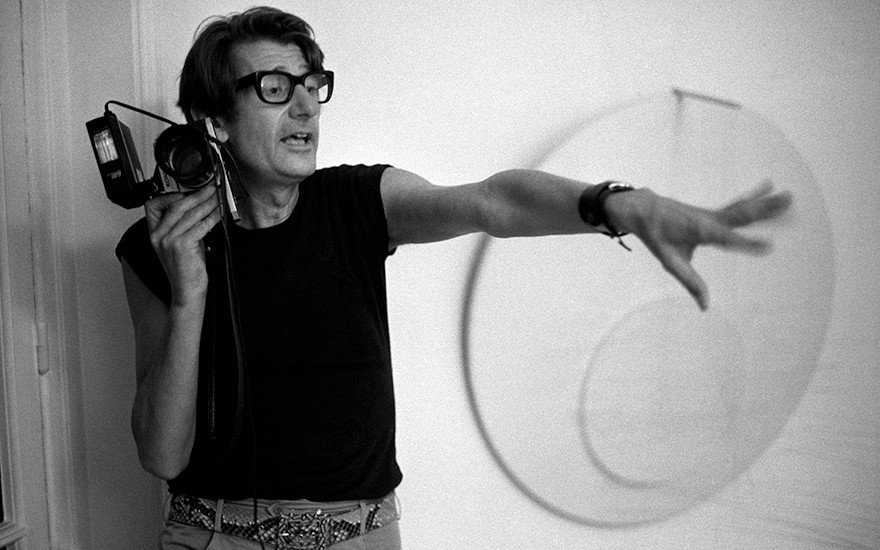

At the Centennial of Helmut Newton’s birth where does his legacy stand today?

By Adam Hencz

“Any photographer who claims not to be a voyeur is either an idiot or a liar.”

— Helmut Newton

This year marks the centennial birthday of one of the masters of late twentieth century photography. Helmut Newton overturned the prevailing conventions surrounding both fine art and fashion photography, bringing controversy and conversation to each and in the process innovated a new formula for editorial photography. His works reverberated through fashion, art, and film, and dominated glamorous high-gloss magazines for decades. As a photographer, who straddled the gap between art and commerce, Newton explored the darker side of sexuality and reveled in nudity and erotic fantasies. He is criticized for his overly suggestive depiction of women, however he continuously strived for a contemporary female image at a time of gender and sexual liberation. His models were photographed as strong, triumphant and liberated, and with sole and total command over their bodies. Newton explored all the angles and planes of the female body—his models would not be turned shyly away from a camera—everything was defiantly on display.

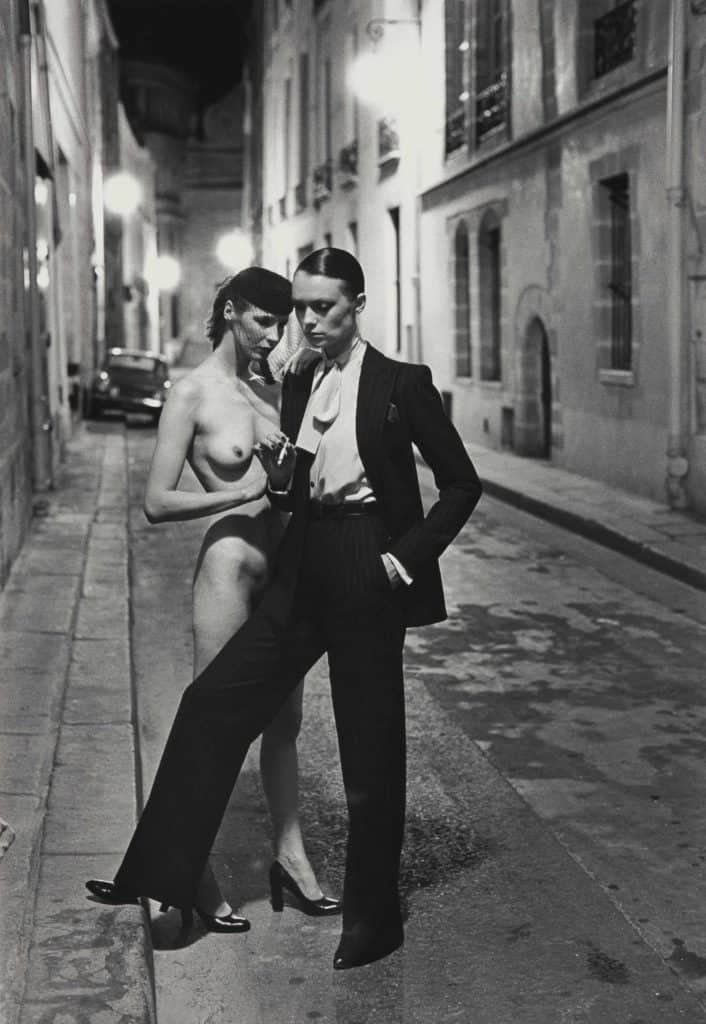

Models (Left to right): Alexandra Pin, Henrietta Allias Purcell, Lisa Thorensen, Sylvia Gobbel.

Born in 1920 in Berlin as Helmut Neustädter to a Jewish family, Newton expressed an early interest in photography. He picked up his first camera at the age of 12 and in the following years he was often truant from school in order to photograph childhood girlfriends in the streets of Berlin. By the age of 16 it was clear that Newton would not be joining the family-run button factory and he started to work as an apprentice to portrait, nude and fashion photographer Else Neuländer Simon, better known as Yva, in Berlin-Charlottenburg.

His family was forced into exile after fleeing Germany in 1938, landing in Singapore, where Newton found work as a photographer at a local magazine. He was interned in Singapore and sent to Australia, where he served in the army for five years, eventually becoming an Australian citizen. Newton set up a studio in fashionable Flinders Lane in Melbourne going into partnership with Henry Talbot. Newton worked on fashion, theatre and industrial photography in the affluent postwar years. In 1947 he met actress June Browne, who was a fellow photographer and successfully shot under the pseudonym Alice Springs. The two married one year later and were working and living in close companionship for the rest of their lives. It was not until the end of the ‘50s that Newton and June returned to Europe, where he started shooting for British and French Vogue, Elle and Playboy. He was a working photographer gaining popularity through the ‘60s until a hedonistic lifestyle took its toll.

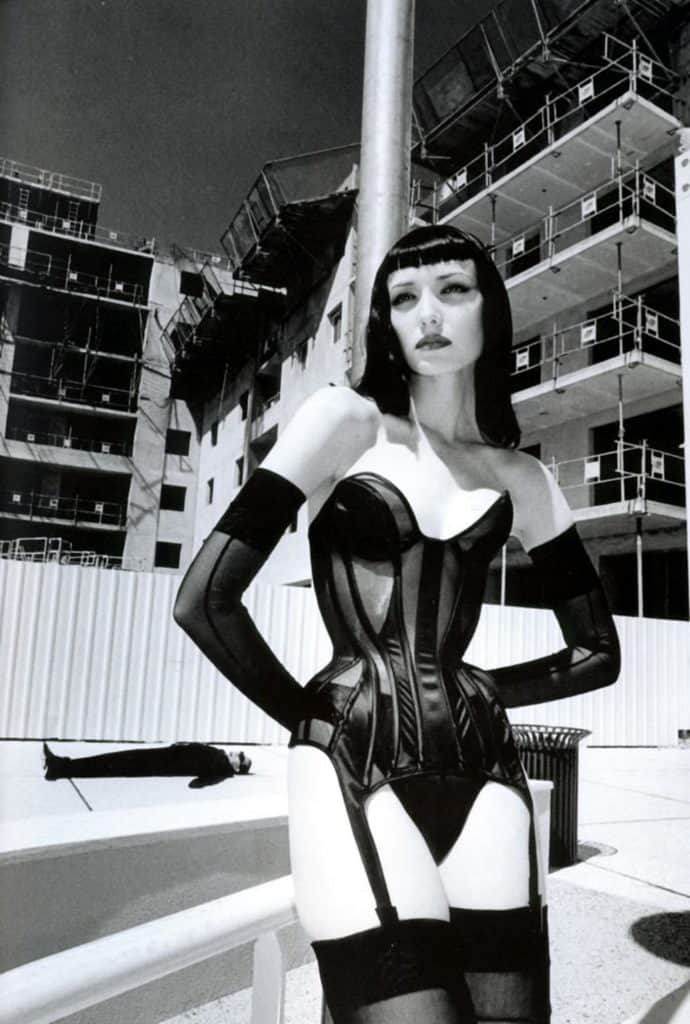

In 1971 Newton suffered a near-fatal heart attack and became hospitalized several times. Realizing that life is short, his approach to photography greatly changed, and he poured more of himself into his work than ever before. “The unnecessary work and the frantic competition are finished!” he revealed in Filthy magazine in 1976. “Today, I only take pictures for money or pleasure.” He began producing incendiary and seductive black-and-white series of nudes, or semi-nudes in settings that overturned the prevailing conventions of fashion photography. His photography exploded into the mainstream in the ‘70s, through partnerships with Yves Saint Laurent and Chanel, but primarily thanks to the striking photographs he produced on commission for French Vogue. His artistic talent gained recognition, which allowed him to complete more autonomous projects. He staged his first solo exhibition in 1975 at the Nikon Gallery in Paris and a year later, his first volume of photographs White Women was published. Over the course of his career spanning five decades, he would go on to exhibit worldwide and was featured in magazines and numerous monographs.

“The world needs a form of provocation, because it stimulates thought and conversation.” — Charlotte Rampling

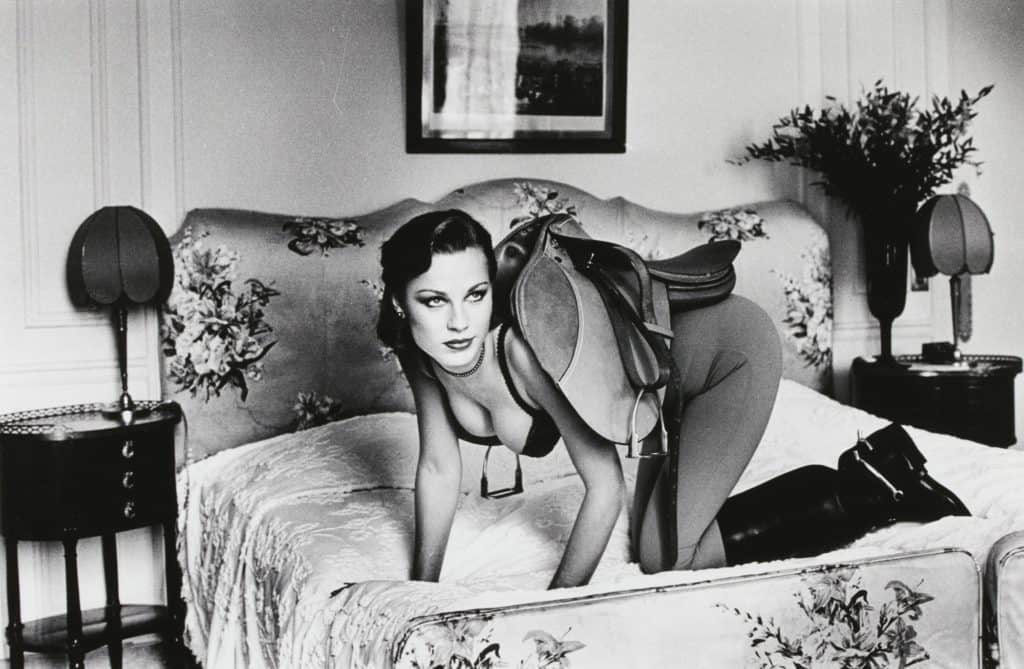

His photography was considered sexist by some and empowering by others. Susan Sontag criticized him during a shared appearance on a French television show countering Newton’s “I love women” with “A lot of misogynous men say that. I am not impressed. The master adores his slave. The executioner loves his victim.” The work speaks for itself, she concluded. The women in his photographs were often nude or semi-nude, tall, thin, full-breasted, embodying a male dictated female ideal at odds with the burgeoning feminist movement. If dressed, they were often outfitted in fetish wear, like pleather corsets, lace lingerie, or thigh-high stockings or boots, or dressed in the costume tropes of men, including evening wear or tailored business attire. Newton viewed the protagonists in his pictures as powerful women, the nude female body as a symbol of a woman’s strength and control. With the encouragement of his wife, June, Newton pursued themes of voyeurism, lesbianism and fetishism in his work.

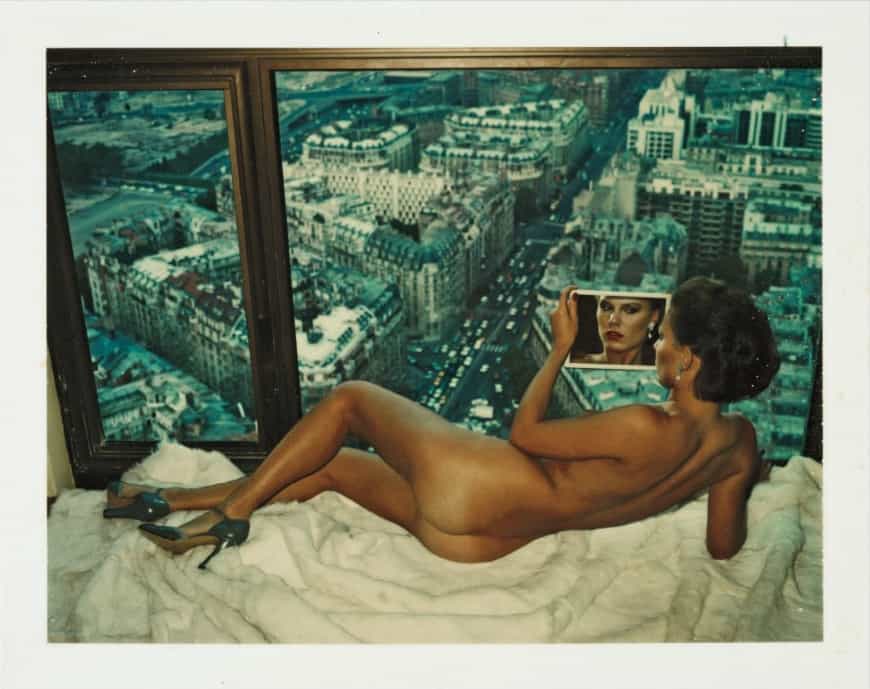

Apart from the 1981 Big Nudes series, Newton preferred to shoot in streets or interiors, rather than studios. Hotels, pools and streets were among his favorite sets. He created controversial scenarios inspired by film noir, expressionist cinema and surrealism, with bold, high contrast, lighting.

Newton used polaroids extensively, beginning in the ‘70s, especially for his fashion photo shoots. As he once described in an interview, this satisfied his impatient urge to know immediately how a certain situation would look as a photograph. In this context, he considered the Polaroid as an idea sketch in addition to testing the actual lighting situation and image composition. In 1992 Newton published Pola Woman, an unconventional book consisting only of his Polaroids.

Shortly before his fatal car crash in 2004 at his age of 83, Newton donated approximately one thousand of his works to his native city, and established a foundation in Berlin that has been managing the preservation and presentation of his work even since. His work was a mirror to a society and fashion industry that has changed and evolved ever since, therefore, one could find his depictions of hyper-sexualized beauty standards for women less engaging today as they were perceived at their time. In the first documentary on Newton’s life and work The Bad and the Beautiful released earlier this year, German director Gero von Boehm opted for an interview-heavy format as an opportunity for the women who were voiceless in Newton’s photographs to finally speak and share their viewpoints. “Helmut gave me immense inner strength, and if he had not taken these pictures of me, my whole career would have been different,” says Charlotte Rampling in the film. “He was a little bit of a pervert but so am I, so it’s OK,” remembers Grace Jones, who recalls clearly having a blast working with the man. “His photography wouldn’t be possible at all today,” says director von Boehm. “It was a revolution at the time.” Newton declared that there are “only two dirty words” in any of the three languages he spoke — art and good taste. He never let either limit what he was going to portray.

Relevant sources to learn more

Styles Of Photography

Helmut Newton Foundation

The Photography of Karl Lagerfeld

Nastassja Kinski & the Serpent