Articles & Features

An Abridged History of Video Art Part I. The Conceptual Pioneers, from the 60s to the 80s

By Shira Wolfe

In the second half of the twentieth century popular entertainment began to move away from the culture of books, magazines and periodicals that had held sway for centuries, and into the realm of the moving image. The exciting new cultural developments, allied to rapid technological progress and the availability of consumer electronics, ensured that television and film became ripe for exploitation by artists, both as subjects for artistic commentary such as in the work of Pop artists, but also to explore as a medium and vehicle for the artistic content itself. However, despite the fact that video art is arguably the most apposite medium for echoing the mores and characteristics of contemporary society, there are several reasons why video art is still considered amongst the most challenging for art lovers and and collectors. Many video works seem as if they might require special access to expensive or unwieldy technological equipment, whilst the seeming lack of tangible object ownership unlike that associated with painting and sculpture creates additional wariness. However, the most common objection seems to be the time based element of the work. Time, for many, is the most valuable commodity of all, and the very fact that a video work demands a greater kind of commitment and attention than a painting or a sculpture, is enough for it to be considered too challenging for many to be truly embraced in a broad sense.

Many of the early prominent video artists were those involved with concurrent movements in conceptual art, performance, and experimental film. These include Americans Vito Acconci, John Baldessari, Joan Jonas, Dan Graham, Bruce Nauman, Peter Campus, William Wegman, Martha Rosler and many others. There were other innovators were who were interested in the formal qualities of video as a means of image making and employed video synthesizers to create abstract works.

In the 1980s video art enjoyed a further renaissance, when advances in editing technology for the individual user led to a spate of works that developed both narrative and non-linearity, but also stream of consciousness explorations of psychology, which were especially served through advances in technology that could facilitate interactivity.

This collection of iconic works from the early history of video art is by no means exhaustive, but should serve as a concise introduction to video art for the uninitiated, or a pleasing compilation of some the genre’s highlights for afficionados.

Nam June Paik

Nam June Paik was a Korean American artist, widely considered to be the founder of video art. From 1962 he was a member of the avant-garde art movement Fluxus, and was the first proponent of utilising television sets as the principal material component of his sculptural assemblies. He is credited with one of the first video works in the mid-Sixties after the introduction of hand held video recording equipment for the general population, making increasingly elaborate stacks of video monitors and television based sculptures from the 1970s onwards. In the 1963 exhibition Exposition of Music-Electronic Television at the Galerie Parnass in Wuppertal, Paik scattered televisions throughout the space and used magnets to distort the images playing on the screens. An early piece that further sealed his international reputation was TV Cello, which synthesised video, music and performance, and although performed in various iterations, consistently showed a cellist performing with two stacked televisions standing-in as a physical surrogate for an actual cello, on which screens showed the strings of a cello being played as the seated cellist moved her bow.

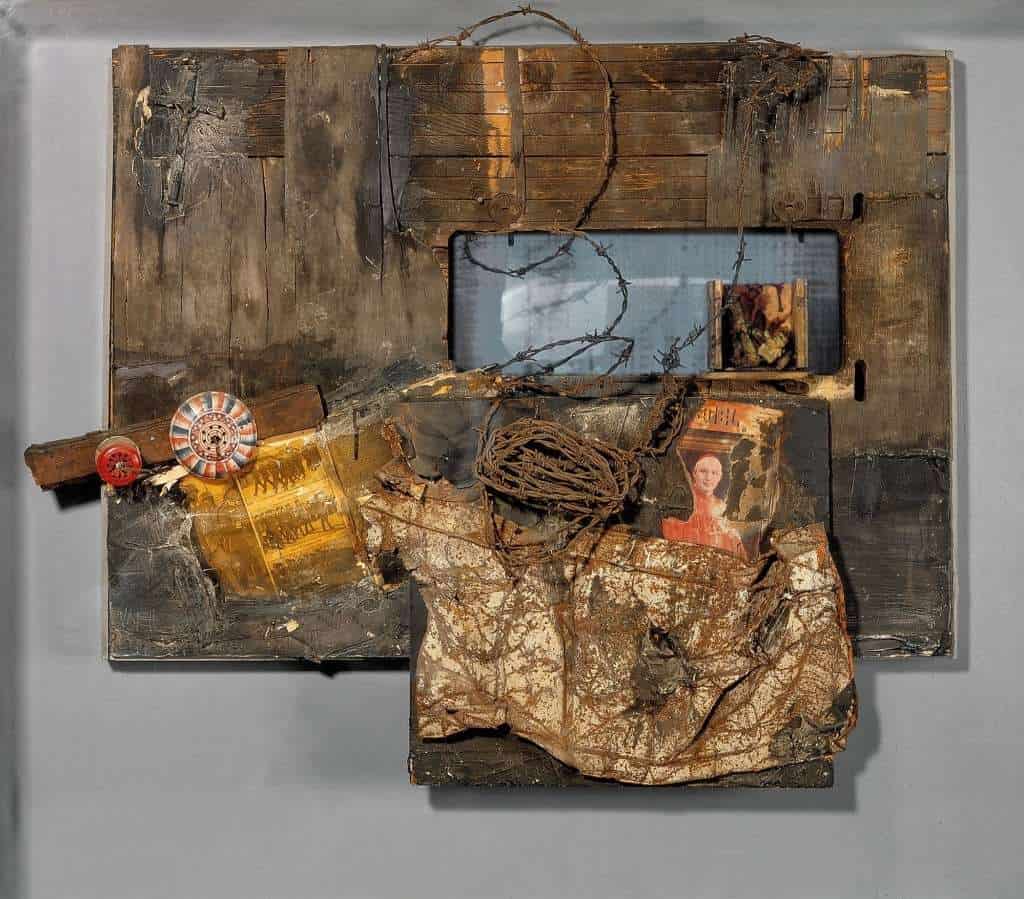

Wolf Vostell

Also a founding member of Fluxus, and influenced by the work of Stockhausen, as well as his personal correspondence with Nam June Paik and Joseph Beuys, Vostell was also an early innovator and is considered the first artist to physically place a television set into a work of art in his seminal assemblage piece The Black Room Cycle of 1958. His 1963 work Sun In Your Head is among the first purely video artworks ever made, and is emblematic of Vostell’s approach to collage based image making, transposed to the video medium.

Andy Warhol

No survey of the second half of the twentieth century would be complete without mentioning Andy Warhol. More commonly known as the pop master of the silkscreen painting, Warhol was also the maker of over 400 films. From the early minimal works such as Sleep and Blow Job, to the later epic The Chelsea Girls, Warhol was a highly active disciple and proponent of the moving image, at least from the time he acquired his first film camera in 1963. Shot in 1964, and lasting a soporific five hours and twenty minutes, the film Sleep was one of his first experiments in film making and consists of Warhol’s lover at the time, John Giorno, doing nothing other than sleeping. Described by Warhol as an “anti-film”, he would later extend the same filming and cutting technique to eight hours for his subsequent film Empire, constantly solely of footage of the Empire State Building.

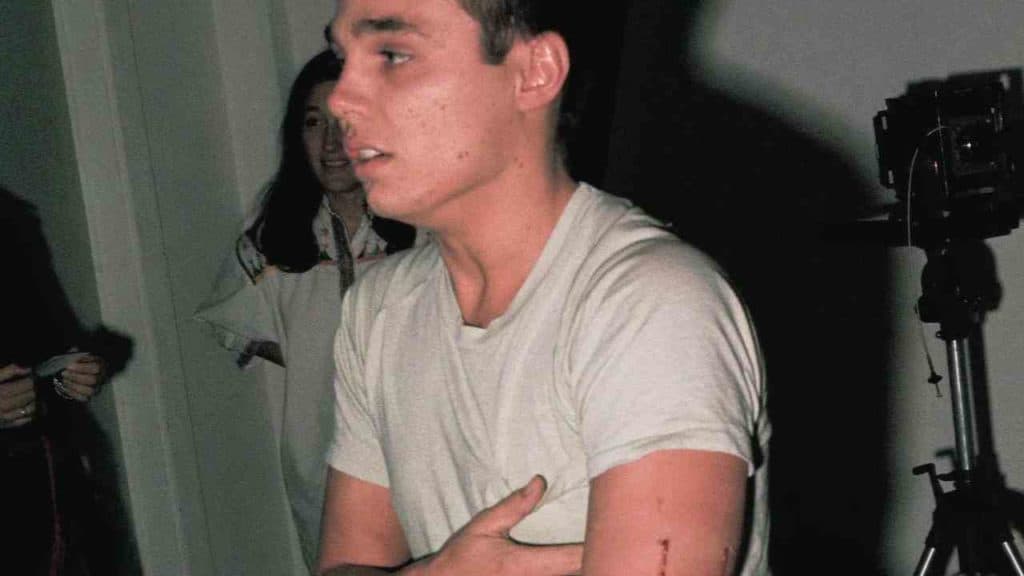

Chris Burden

Chris Burden was an American artist who became prominent in the late 1960s and 70s working in performance, sculpture and installation. His video works tended to function as records as of his performances or happenings. In 1971, at a gallery performance, he arranged for a friend to shoot him in the arm with a small calibre rifle, intending for the moment that the bullet entered his body to be a living sculpture. The performance, and recording of it, both came to be known as Shoot , and were described by Burden, the artist and principal actor, “The moment when I was getting shot was the sculpture, just that instant when the bullet travelled from the gun into my arm. And then after that, it’s all over. That was the sculpture, it was less than a second.”

Dan Graham

From the late 1960s for more than a decade, Graham shifted his practice towards performance, in which he explored various perceptual and kinetic exercises, utilising the camera ostensibly as an extension of his body. His video works were also often recordings of his performances, a body of work best summarised as a systematic interrogation of phenomenological experience. In his first film Sunset to Sunrise from 1969, Graham moved the camera in the opposite course to the path of the sun, creating a conceptual inversion of the passage of time. This seminal work set the tone for much of his practice, described by Graham as “subjective, time-based processes”.

Arguably of greater renown is his 1975 video work Performer/Audience/Mirror. Recorded at Video Free America in San Francisco in 1975 the work is a phenomenological inquiry into the audience/performer relationship and the arising questions of subjectivity and objectivity. In the piece Graham and his seated audience are contained within a room, and the artist addresses this collective both directly, and also indirectly by way of a mirror which runs alongside one wall—he describes the audience and what they signify to them. He then turns to face the mirror and describes himself, narrating his posture, movements, and appearance while standing in front of the gallery audience. Graham described this dynamic thus “First, a person sees himself ‘objectively’ (’subjectively’) perceived by himself, next he hears himself described ‘objectively’ (subjectively’) in terms of the performer’s perception”. Showing the influence of the philosophic writings of Jacques Lacan, Graham sought the verbal, self-completing approaches of Lewitt and Baldessari but with the added dimension of a live and performative self-portraiture.

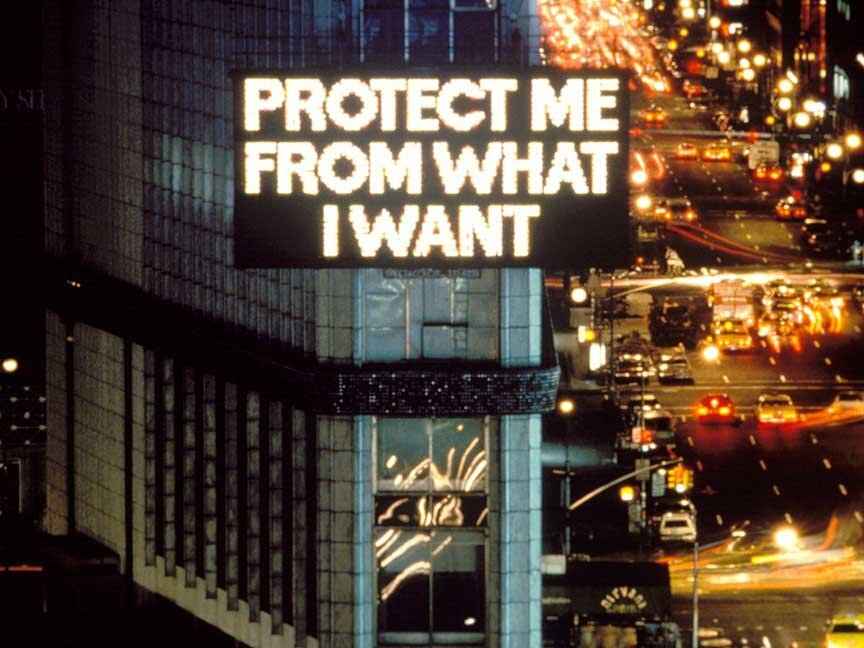

Jenny Holzer

Jenny Holzer took video works in an altogether different direction, ignoring image and focussing only on text. Most of her work is premised on neo-conceptualist ideas about the communicative power of different language choices and their presentation in public spaces. Belonging to a loosely affiliated group of women artists who rose to prominence in the late 1970s and 1980s, including Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, Sarah Charlesworth and Louise Lawler, all of whom shared an interest in making social, often feminist, commentary an implicit part of a visual object’s role. The public dimension is integral to her work, with her large scale works often displayed on electronic LED billboard displays, mimicking the potency of display more commonly associated with breaking news and financial market electronic tickers. In the 1980s her terse one-liners were displayed on electronic signboards in Times Square, New York and Piccadilly Circus in London. Based on her Truisms series, which consisted of made up “mock cliches” which sounded like they could be well known aphorisms, Holzer’s language compositions are deliberately challenging, often presenting a spectrum of contradictory opinions and ambiguous clarity, Holzer seeks to force people to question “the usual baloney” that is directed them constantly in the course of daily life.

Bruce Nauman

In the 1960s Nauman made a number of video works, such as Art Make Up where he was the subject of the recording. In 1973 he employed professional actors for the first time in his video works, before abruptly halting works in this medium. After a hiatus of twelve years he returned to it in 1985 whereupon he made a series of works characterised by confrontation and jarring aggression. Stemming from feelings of frustration and anger about the human condition, Nauman explained that he wanted to explore “how people refuse to understand other people. And about how people can be cruel to each other. It’s not that I think I can change that, but it’s just such a frustrating part of human history.”

In a fascinating explanation of the works inception and narrative Nauman recounted “Violent Incident” begins with “what is supposed to be a joke – but it’s a mean joke. I started with a scenario, a sequence of events which was this: Two people come to a table that’s set for dinner with plates, cocktails, flowers. The man holds the woman’s chair for her as she sits down. But as she sits down, he pulls the chair out from under and she falls on the floor. He turns around to pick up the chair, and as he bends over, she’s standing up, and she gooses him. He turns around and yells at her – calls her names. She grabs the cocktail glass and throws the drink in his face. He slaps her, she knees him in the groin and, as he’s doubling over, he grabs a knife from the table. They struggle and both of them end up on the floor.”

The scene sequence was performed in three other versions: the couple exchange roles, and then it is played by two men and then two women. Each version was edited with slow-motion, with colour changes, and with footage of rehearsals in which the action is overlaid with a man’s voice shouting directions. The twelve permutations are subsequently displayed and played simultaneously in twelve monitors stacked in four columns of three. The result is a chaotic and cacophonous wall of sound and vision crackling with aggressive tension.

Gretchen Bender

and another installation of Total Recall at The Schinkel Pavilion: https://vimeo.com/128055524

Gretchen Bender was an American artist who worked in film, video and photography, and also of the so-called Pictures Generation which gained dominance over the contemporary art world in New York during the 1980s. At the end of the 1970s she began to assimilate abstract computer graphics into her work, and by 1982 was converted to using television imagery as her principal source. Considered too technical a challenge for many artists, bender taught herself how to bend her new found medium to her needs, developing sophisticated video editing skills necessary to create her rapid-fire spliced film images into powerful contemporary essays on the power of the moving image. Interviewed by Andy Warhol for his Interview magazine in 1985, Bender asserted that “artists should be spending their money on VCRs instead of paint and canvas”. Named after the eponymous Paul Verhoeven film, Gretchen Bender’s ”Total Recall” is a monumental installation—an 18-minute “electronic theater,” as the artist calls it, setting disparate visual material to a pulsating soundtrack, and creating a media-image overload. Designed to be confrontational, jarring and simultaneously subliminal, Bender’s work intended to wake the viewer into a more alert state of consciousness, encouraging them to think critically about the content they usually consumed, and set in contrast to the trance like viewing she considered typical of conventional television watching.