Articles & Features

A Short History of Video Art Part II: Stories Of And For Our Times

By the end of the 1980s the landscape for video art had become transformed. The early pioneers, whose work grew out of their desire and ability to newly document conceptual ideas and performances, began to be joined by a new generation of artists who undertook to find new applications for the possibilities of video art. Technology made more sophisticated effects possible, and certainly some artists embraced these possibilities to affect and expand the visual language of sculpture. Others found ways to comment on video’s increased prevalence in contemporary media and culture, using its potential for coruscating critiques of modern society. Narrative, psychology and anthropology fused as artists instinctively understood that the medium of video could be applied as never before to the expansion of fine art and, most significantly, as the most apposite mirror to hold up to the fast moving society rapidly changing around them.

Gary Hill

Gary Hill is an American artist and considered one of the most innovative founders of today’s highly varied application of video media to art production, due to his his single channel video works and sound and video installations of the 1970s and 1980s. As technology advanced so did the means for using it in his works, especially in the facilitation of experiential interactivity. Originally trained in sculpture, Hill is interested in linguistics and the unique possibilities that video offers to create new languages through combining the visual with the aural and the textual. Hill uses video to create installations which draw the viewer into environments in which their perceptions of reality are challenged. Today he is also best known for creating profoundly affecting ontological experiences through synesthesia and other perceptual and spatial disorientations. He has even deconstructed and reconstructed the very materials of video art in order to push its performative ability in a physical space to its absolute limits.

“No artist of Hill’s generation probed this medium with such invasive scrutiny, and none deployed it with such protean irreverence”

Lynne Cooke, Art historian

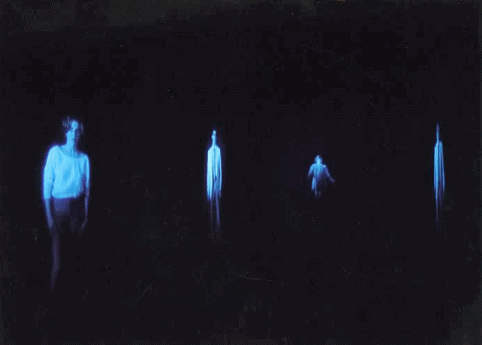

In the now legendary Tall Ships of 1992, visitors enter a narrow corridor, which is shrouded completely in darkness. It is a technologically ambitious, entirely silent, sixteen channel video installation that comes into being through the presence of a viewer—set up so that whoever walks into the darkened passageway triggers the projection of figures onto both side walls along the length of the space, a few feet apart on either side, via computer-controlled, pressure sensitive switch mats. There is a single projection on the very end wall, located precisely 27 meters from the entry. The figures come into into being at around eye level, apparently at the very edge or perimeter of the environment the viewer is contained within, hovering for a moment at this perceived horizon edge before moving forwards. The black and white, human scale representations of ordinary people of varying ethnic origin, ages and genders then move towards the viewer, only to stop almost at the point of meeting, a point at which the figure reaches life size and in a highly charged moment of almost-yet-thwarted intimacy. The figure lingers as long the viewer remains in place, and then recedes back into the darkness when the viewer continues his or journey along the passage. There is no source of light—it is the figure itself that gives off the light and is seen directly on the wall. The disquieting illusionary physicality of the figures gives the viewer, who is also aware of the presence of other ‘real’ visitors in the space, a unique experience of this uncanny installation. The incorporation of the element of regulated chance in Tall Ships means no two experiences of the work are exactly the same, but the silence of these sepulchral figures as they approach, pause and turn away from us makes the sensation one of simultaneous distance and intimacy, both literal and psychological.

Gillian Wearing

Turner prize winner Gillian Wearing is one of the most fascinating video artists working today. Describing her approach as “editing life” and a “kind of portraiture” she has proven to be most insightful when turning her camera on the indiosyncracies of society and its various interpersonal relationships. Her trademark approach involves the mimicking of a documentary techniques to reveal hidden realities about the inner lives of her subjects, their propensity to reveal or conceal them, and the accompanying investigation into truth or fiction. Many of her works reveal an unsettling divide between public persona and inner self. Her body of work is extensive, and she is well known for many iconic pieces, that also include more conventional photography and sculpture.

Her early Dancing in Peckham from 1994 is a 25 minute video that shows Wearing dancing in a public shopping centre in Peckham, South London, to a soundtrack that only she is party to, a soundtrack not supplied by a music device but only through recollection in her head. The piece was inspired by a scene witnessed by Wearing as she strolled through Royal Festival Hall. A jazz band happened to be playing nearby and Wearing became captivated by the actions of a particularly dedicated spectator—a woman overcome by the desire to move her body to the music, and in a Bacchic way that made her seem completely overcome by the moment, her moment, and oblivious to everyone around her. Wearing thought of asking the woman to recreate her dance for a video but concerned that this would seem condescending, determined to perform the scene herself. Having prepared and practised her moves prior to the performance/recording, in the video Wearing gyrates, contorts and throws her hair around in an intensely committed manner. Her face is serious and concentrated but her appearance is faintly ridiculous and subjects her to the pitfalls of public embarrassment or shame. No-one approaches her, stops her or communicates in any way. What are they thinking as they pass by with a disdainful attitude? Nowadays the reflexivity of the work is much less clear to viewers as the tropes of social media overwhelm our society and reality television extremely pervasive as a cultural influence. However, with none of these reference points altering the contextual reading at the time of its making, Wearing’s work can be viewed as a multi-layered portrait of both the individual, the body, their sense of self, and his or place in society at large. Her performance can be viewed as that of a completely other person than herself, such is the abstracted nature of her own movements, a portrait of the anonymous woman she witnessed at Festival Hall and has chosen to mimic, but also also a highly nuanced self-portrait and image of what it is to be completely lost in a private moment.

Wearing’s unique approach is encapsulated perfectly by 1997’s 2 into 1, a short video which shows a mother and her two sons, each filmed separately, speaking in a simple documentary format about their feelings for various aspects of their relationship. The dialogue for each has been switched, so that, via lip-synching, the sons appear to speak the words of their mother and vice versa. The voiceovers are executed with such precision that they are scarcely believable, heightening the disturbing sense of uncanny. As the play continues between the subjects in the video, the viewer learns more about each individual and the family dynamics from their respective viewpoints, doing so in a fashion that emulates ethnographic practices similar to the researcher in the field who produces knowledge and conclusions based on detached observation. Yet Wearing’s work radically changes documentary practices that long for objective truths and familiarity into its inverse, the unfamiliar.

Long before contemporary media culture in our hyper-connected world heralded the death of privacy, Wearing was already quietly obsessed with that shift in propriety and candour and was among the first to anticipate and dramatise its implications. “I think media has changed us all” she observed in a 2012 interview. Eight years on this truism is more pronounced than ever. Wearing’s brilliance lies in her presence in recognising it before most others.

Matthew Barney

Matthew Barney is an American artist and avant-garde film director who has pioneered the use of lavish cinematic effects in his video works, whilst incorporating sculptural, drawing and photographic practices in the shaping of those filmic environments, and into works he derives from them. Intertwining complex and esoteric themes of biology, geology, mythology, as well as themes of sexuality, human striving, success, failure and conflict, his early works combined performance and video.

In his brilliant Cremaster cycle, a sequence of 5 films made non-sequentially between 1994 and 2002, he created one of the most legendary video art works of all time, and over nine hours of stunning and dense psychedelia. Somewhere between a traditional feature film and a lavish installation, the cycle unfolds not just cinematically, but also through the photographs, drawings, sculptures, and installations the artist produces in for and conjunction with each episode, and which he displays in gallery and museum exhibitions outside of the filmic context. Its conceptual departure point is the male cremaster muscle, which controls testicular contractions in response to external stimuli, mostly temperature. Each film is replete with bizarre and oddly dressed characters performing arcane rituals and puzzling tasks, hybrid beings and spectacular, sometimes perverse, baroque imagery—described by Guggenheim curator, Nancy Spector as “a self-enclosed aesthetic system.”

Throughout the five films the project contains a litany of anatomical allusions to the position of the reproductive organs during the embryonic process of sexual differentiation: Cremaster 1 represents the most “ascended” or undifferentiated state, Cremaster 5 the most “descended” or differentiated. The cycle repeatedly returns to those moments during early sexual development in which the outcome of the process is still unknown. In Barney’s metaphoric universe, these moments represent a condition of potential and possibility, yet to be shaped and formed. As the cycle evolved over eight years, Barney looked beyond biology as a way to explore the creation of form, employing narrative models from other realms, such as biography, mythology, and geology. The photographs, drawings, and sculptures radiate outward from the narrative core of each film installment. Barney’s photographs—framed in plastic and often arranged in diptychs and triptychs that distill moments from the plot—often emulate the formats of classical religious and mythical portraiture. His graphite and petroleum jelly drawings represent key aspects of the project’s conceptual framework. Overall, Barney’s epic meditation on religion, mythology, and, at its core, creation itself, is one of the most sweepingly ambitious and visually sumptuous art works of all time, irrespective of medium.

Pipilotti Rist

Pipilotti Rist is a Swiss artist best known for creating video installations and immersive video based environments, often characterised and influenced by surrealism, music videos, technology, popular culture and the early historic video work of feminist artists like Carolee Schneemann and Joan Jonas. Ever is Over All of 1997 is one of Rist’s first large-scale installations, infused with the optimistic magical realism of much of her work, and consisting of large screens articulating the space in which it is installed and lending a significant spatial dimension to her rich visual language. In the case of Ever is Over All imagery suggestive of female sexuality, connoted by enhanced and lushly, hyper-saturated images of nature and the everyday. Her worlds meld reality with fantasy. Shot in a single take using publicly available consumer electronics, the work emphasizes the painterly qualities of standard-definition video, in which the pixels or resolution noise that compose the image are visible, and can be considered a constituent part of the painterly imagery.

Accompanied by a dreamy musical soundtrack, the installation consists of two overlapping video projections. To the left of the work on a huge screen a woman proudly and confidently strides down a city sidewalk, smiling serenely. She carries a tall, tropical type flower of a variety that is also seen on the screens to the right, but in that context they are blowing in the breeze in a field of natural habitat. Both videos have been slowed to a hypnotic pace. Suddenly, and without warning in an inexplicable burst of violence, the protagonist swings the flower like a hammer at the window of the parked cars, transforming from a jovial pedestrian into a maniacal enacter of violence. The windows smash dramatically immediately upon impact; implausibly, the flower is a weapon strong enough to break glass. As luck would have it a police officer is also walking down the street, no doubt to apprehend the woman. However, she simply smiles in approval and strolls on by. Rist’s destructive gesture becomes instead a cathartic and hopeful one—the tacit approval of the authority figure dissipates the tension arising from the act of violence and instead it becomes a whimsical purging.

Douglas Gordon

In 2005 Scottish video artist Douglas Gordon and his collaborator Philippe Parreno set up multiple cameras and microphones in order to follow iconic football player, and one of the global game’s most stellar talents, Frenchman Zinedine Zidane over the course of a single match, whilst representing the colours of his club side Real Madrid. Assembled from footage from seventeen cameras placed around the stadium, including pitch side and grandstand vantage points, Zidane A 21st Century Portrait, a 90 minute film (the exact duration of the match itself) captures Zidane from multiple angles, both up close and afar, but remains assuredly fixed upon his every move, with and without the ball, irrespective of other action unfolding elsewhere within the context of the soccer match in which he is participating. Moodily scored by avant-garde Scottish band Mogwai, the soundtrack features slow, dark melodies fusing brooding rock, haunting piano, gentle guitar melodies and electronica sensibilities, as well as some ambient noise from the stadium and player himself.

The film itself, unusually for fine art, chooses to focus on a single football player, the ultimate populist game and far removed from the more usual high-minded subjects often chosen as subjects by fine artists. The cinematography, rhythm and music combine to form a breathtaking ode to the strivings of the lone athlete, a portrait depicting the balletic poise and physical durability of the human body, and the nature and cult of celebrity in today’s society. Inspired by portraiture ranging from Velazquez to Warhol, Zidane: A 21st Century portrait bridges high and low, cinema and football, populist and esoteric, and is widely regarded as one of the finest video works of all time, one of the most important and insightful football films ever made, and one of the finest studies of man in his place of work.

Christian Marclay

Christian Marclay is a Swiss American artist who practices as both a visual artist and composer. His work explores connections between sound, noise, photography, video, and film, and his work is widely acknowledged to be a pioneering exemplar of multi-media collage, whereby these elements are edited together into a singular aesthetic experience. In the 1970s he began using gramophone records and turntables as musical instruments to create sound collages, techniques that paralleled the advent of turntable work in hip hop culture, but developed independently of it.

“I’ve never been a big cinephile, which may be why I could treat ‘The Clock’ like a puzzle and force the pieces to fit together in odd ways”

Winner of the Golden Lion award at the 2011 Venice Biennale, Christian Marclay’s The Clock is a cinematic tour de force of both sound and image that unfolds on the screen in real time through more than 12,000 film excerpts that collectively form a 24-hour montage, edited together to form a fully functioning timepiece. Appropriated from the last 100 years of cinema’s rich history, the film clips are spliced together to accurately chronicle the hours and minutes of the 24-hour period, most often by displaying a watch or clock—in short a 24 hour clock composed entirely of film snippets that each explicitly show or demonstrate the actual time. The work incorporates scenes from iconic, obscure and esoteric films, running the full gamut of filmic drama, suspense and serenity, and including car chases, bank heists, western high-noon shootouts, and showing scenes from the courtroom to the boardroom, and everywhere in between. The time itself is depicted by way of wristwatches sundials, hourglasses, grandfather clocks, pocket watches, blinking kitchen appliance LEDs – and the list goes on. The work took three years to compile with Barclay and his assistants combing through the entire history of film to painstakingly select its constituent parts.The work is an immersive experience and creates an all-consuming trance in the viewer as they become absorbed in all the different ways time is represented. The work is also a meticulous record of human activity, a catalogue of the things people do to fill the 24 hour cycle, which of course is the predominant way we measure the rhythm of our lives. Patterns and behaviours are recorded and played back to us – it is a mirror of human experience, there is no linear narrative and time is the common denominator for all. Film fans have the opportunity to watch out for and recognise moments from iconic films and the many famous faces that populate them. Essentially a vast and ambitious memento mori, The Clock is a reflection on time and how precious it is, whilst also offering the paradox of suspending time in favour of actually watching it unfold.

Doug Aitken

“Song 1 is based on one song, what I think is a very perfect pop song. I wanted to take this one specific song and see if that could become the structure for this artwork, and if that song could be reinterpreted in many different ways and eventually create its own landscape.”

Doug Aitken was born in 1968 in California and lives and works in Los Angeles. He works across multiple media but is most known for his monumental view installations. He has created enormous video projections both indoors and out, covering entire buildings, the sea bed and even a mirrored building in the desert with his imagery.

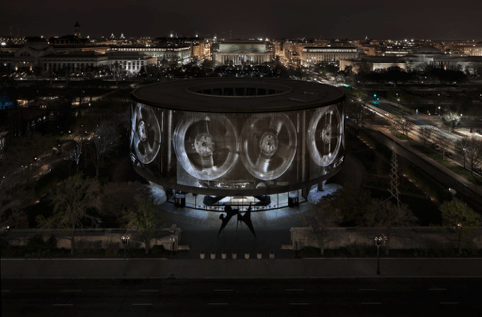

SONG 1 from 2012 is a widely exhibited and well loved masterpiece of Aitken’s oeuvre. It is a 35-minute-long sound and video installation created by the artist and in its numerous presentations has been projected variously onto the circular exterior of the nearly windowless Hirshhorn Museum in Washington DC, and on the inside and outside of massive circular video screen constructions. Within the framework of a classic pop song, the iconic “I Only Have Eyes for You,” Aitken has created a compelling and spatial video work, essentially a monumental sound and video collage, reflecting present day urban landscapes and the diversity of its inhabitants and activities.

The song itself is a classic jazz standard from 1934, known across the world for its melancholy tune and romantic lyrics. Deeply embedded in the musical DNA of American cultural life, it has appeared in countless versions – the best known being The Flamingo’s version from 1959, and characterized by its slow and lilting ‘doowop’ rhythm and blues stylings. Aitken invited different musicians to record their versions of the song, echoing the song’s own diverse history and its multiple interpretations through the decades. The song is also interpreted visually as actors both known and unknown appear in the work singing, lipsynching, dancing or just swaying rhythmically to its hypnotic beats.

The visual side of the work oscillates between past and present, from stylized black and white clips that reference the influence of the stage and television screen in popular culture, to present-day modernity represented visually by metropolitan cities with crowds of people and pulsing light, or by vast industrial facilities and factories of mechanised production. Here men and women are seen in these varied environments – the workplace, in cafés, in studios, and in traffic – singing the familiar, yet different and personal versions of the tune. Fundamentally, the artwork is a rhythmic flow of these video clips that are projected onto a large circular screen—it is an immersive artwork for the viewer, one that the audience can both walk around as well as step into. Referencing the cultural history of modernity, the videos both inside and out, play on a continuous loop. Depending when the viewer arrives to commence their watching, they will be confronted by one of any number of participants. It might be the waitress, striding gracefully with a pot of coffee, the singing tuxedoed duo with vintage microphones, snapping their fingers and smoothing their ties, maybe the two dancers, flailing their limbs to a rumbling beat, or the businessman quietly pondering. Perhaps it is the pale-faced woman in the white robe, looking over the city with a serene half-smile, a lone woman in a parking outlet outside a motel, or the machinist working diligently in a factory of glaring illumination, pausing momentarily now and then as they engross themselves in their own private song performance.

In Song 1, the implication remains that all the participants engage in similar searches for love and belonging as described in the lyrics, and a feeling of yearning pervades. These experiences repeat themselves in universally familiar, ‘everyman’ ways across time and place and reminds the viewer of a universality of human experience. The simplicity of the song, the soulful backing choir, and the repetitive of the lyrics and melody emphasize a common ground for all—we are reminded that humanity is linked through human emotions and experience. Visual representations, and juxtapositions, of men and women, vast urbanity and the individual, the present versus the past, leave no doubt that the work is an exploration of modernity and the conditions that influence our lives today.

Ragnar Kjartansson

“I really love country music, just this idea of three chords and the truth.”

Ragnar Kjartansson is an Icelandic performance artist who captures his work in multi-perspective video installations. His works are influenced by film, theatre, music and often by Greek tragedy. Both comedic and laced with pathos, his work are often searingly lyrical explorations of the human ability. Often of long duration and with extensive repetition, they build up towards powerful crescendos of emotion. In his iconic work from 2012, The Visitors from 2012, Kjartansson creates an elegiac paean to friendship, to music, Bacchic abandon and homespun sentimentality.

“I really wanted to do something else, though the idea never really looked good on paper: just making a sentimental country song with my friends in this really great place.”

One Summer evening in 2012, at Rokeby farm, a faded Hudson River mansion in Upstate New York, belonging to bohemian descendants of the storied Gilded Age Astor dynasty, Kjartansson and eight other musician friends from Iceland, each installed themselves in various crumbling rooms of the home, whereupon they perform a song written by the artist’s ex-wife. Each playing different instruments and linked together through headphones, the various performers (Kjartansson himself plays the guitar in the bath) descend into an all consuming and ecstatic rendition of the chorus, “Once again, I fall into my feminine ways”. The resulting film, The Visitors, shown on nine screens, each of which showed one of the house’s performer locations, swells and emotes for its entire 64 mixture duration. Alternately comedic, melancholic, meditative and sentimental, the film is a celebration of human emotion and the power and potential of friendship to unlock and harness these emotions. It is simultaneously simple and sumptuous, but feels always profound. At the film’s end the friends conclude their song, gather on the terrace and then arm-in arm and warmly glowing from their euphoric collaboration meander across fields of aching bucolic beauty into the last glowing embers of days end. It is mesmerisingly beautiful and widely acknowledged to be among the greatest of twenty first century video art masterpieces.