Infrared Photography: The Secrets Beneath The Surface

Article and Features

As detectives follow clues to solve mysteries, so scientists and conservators investigate artworks to solve unanswered questions. Instead of magnifying glasses, binoculars and newspapers with eye holes, they have analytical scientific techniques as tools at their disposal. Among these, Infrared Photography plays a big role and allows scholars to delve into the secrets below the visible surface of paintings.

The process involves examining a painting with an infrared camera using light in the near-infrared region of the electromagnetic spectrum (we usually talk of Infrared Reflectography when a wider range of wavelengths is employed).

To understand how it works, it is useful to picture a painting as a layered structure: each layer is intended to cover the one underneath (except for the varnish which, as a final protective layer, allows us to see the colour underneath). Just as in ordinary light conditions where the varnish is transparent, in infrared light, the covering power of most pigments decreases, thus enabling us to see through them and revealing the hidden layers—showing what the naked eye cannot usually see.

This non-invasive method offers a unique insight into the creative process; in fact, experts can detect underdrawings, pentimenti (compositional changes made by an artist in the course of painting), damages, retouches, as well as recognise when a canvas has been reused and a work painted on top of a completely different composition entirely. Documenting the technical history of a painting is an essential step to understand an artist’s working methods and objectives.

The first use of Infrared Photography in the artistic field dates back to the 1930s and became a routine analysis in the following decades, especially on 15th-century Flemish paintings which provided excellent results due largely to the thinness of their pictorial layers. Reflectography, on the other hand, was invented in the late 1960s by the Dutch physicist van Asperen de Boer, a huge development in terms of technology and what it meant for conservators and restorers.

Still to this day the technique opens up new vistas and provides amazing, and sometimes unexpected, results, of interest to both specialists in the art field and the public alike.

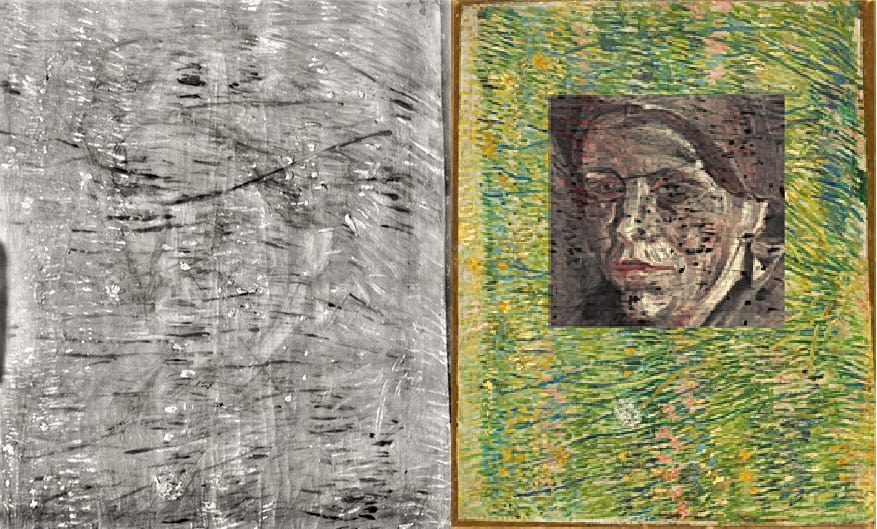

Van Gogh. Patch of grass (1887)

One of the most known of Vincent Van Gogh’s features is his high productivity in contrast to the complete lack of success during his lifetime. However, what most people don’t know is that he was even more prolific than we are aware of since several of his artworks actually hide previous compositions.

Partly due to his ongoing financial difficulties, and partly due to the swift and impulsive evolution of his style, recycling used canvases to paint something new on top was a frequent habit of the artist, and about one-third of Van Gogh’s early paintings are covering something else. Even though the oeuvre of Van Gogh, because of its typical thickness, is not the most suitable for infrared photography, exciting findings have been discovered underneath the painting Patch of Grass, currently held in the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo.

Turning the painting ninety degrees counter-clockwise, the infrared analysis clearly reveals the basic outline of a woman’s head with a hat. If this shape looks familiar, it is because this former composition belongs to a series of studies depicting peasants’ heads realised a couple of years before in the Brabant village of Nuenen and characterised by dark and sombre tones.

Since Patch of Grass was painted after Van Gogh’s move to Paris and his first approach to Impressionism, the artist likely found the woman’s head dated and provincial by then and, in difficult straits, chose to sacrifice it and use it as new support to experiment with bright and vibrant colours.

The amazing result constitutes the first step of a complex and innovative analysis, carried out by an international team of scientists, which has further highlighted the contrast in technique, palette, and intention between the two overlapping paintings.

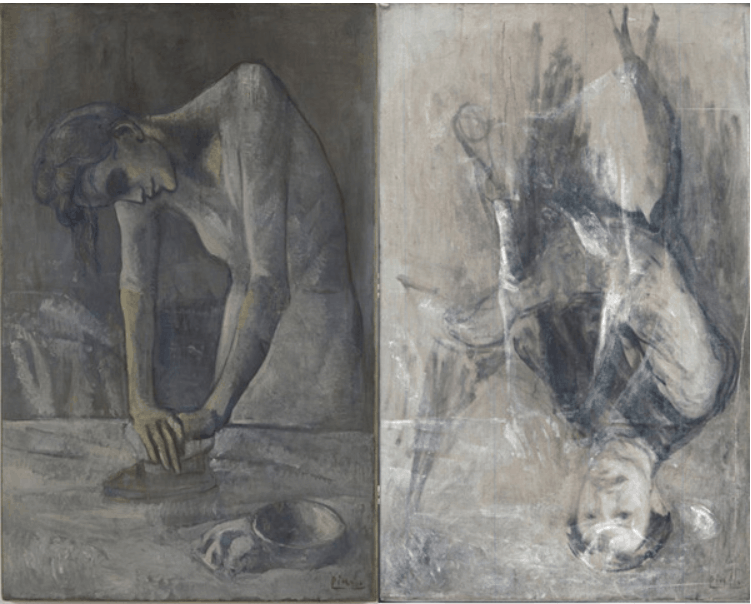

Pablo Picasso. Woman Ironing (1904) and The Blue Room (1901)

Even though it is a known fact that artists have recycled canvases, we may wonder who used them first. Sometimes they might have borrowed them or just randomly found them, painting over someone else’s work. Technology can help us to clarify similar doubts and, occasionally, time comes our way bringing the answer. This is the case of Pablo Picasso’s Woman Ironing (La repasseuse, 1904).

In 1989, the analysis of this melancholy portrait of a Parisian laundress revealed the vague shape of a man beneath the skeletal female figure. Because of technological limitations, it was more of a hint and it was impossible to determine if it was Picasso who actually painted him.

After more than twenty years the Guggenheim Conservation Department resumed the study with the addition of advanced imaging techniques as part of an in-depth survey. The results were outstanding, not only confirming the position of the figure, but giving highly detailed information, from the shape of the eyes and the moustache to the specific clothing.

This time it was finally possible to confirm Picasso’s authorship of both the painted layers since, according to Ms. Stringari, chief conservator and deputy director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation “the drippy quality of the paint and the manner of the brush strokes were similar to several other paintings Picasso had made during that time”.

Though it remains a mystery yet to be solved, who is the man portrayed?

Experts disagree about the man’s identity. After ruling out the possibility that it is a self-portrait (since Picasso apparently did not have a moustache at that time) the most likely options include the sculptor Mateu Fernández de Soto or the artist Ricard Canals, both friends of Picasso.

While in Woman Ironing the artist painted over a rough sketch, there are other examples where he covered up finished works. This is the case of the painting Blue Room, depicting a bathing female figure in a bedroom – probably the young artist’s studio at the time – and early example of the so-called Blue Period.

Some clues suggested the presence of an underlying layer and prompted extensive investigations by experts from the Phillips Collection, National Gallery of Art, Cornell University and Delaware’s Winterthur Museum. Firstly, the surface texture does not match the visible composition, suggesting the contours of an alternative image beneath. It is also visible with the naked eye that The Blue Room is actually thinly painted over a heavier textured coloured layer, leaving areas where the underlying paint shows up.

Infrared Reflectography disclosed a portrait of a man dressed up in Parisian dinner attire, resting his head on his right hand.

Scientists presume that the hidden painting is also by Picasso, and it was completed and dried before being painted over. As with Van Gogh, the reuse of a canvas is attributed to his prolificacy. Biographical information confirms Picasso’s financial difficulties of the time—the fact that the blue portraits did not sell well encouraged the artist to paint over his previous works until arriving at a saleable composition.

Relevant sources to learn more

IR Reflectography – Technical details

Kroller Muller Museum

Guggenheim Museum

Phillips Collection