Articles & Features

Installation Art: Top 10 Artists Who Pushed the Genre to its Limit

Courtesy of David Zwirner, N.Y. ©Yayoi Kusama

Installation Art

Often site-specific, and occasionally occurring in public spaces, the boundaries of what constitutes installation art have been blurred since its very inception as an artistic genre. Though installation art varies widely it can best be thought of as an umbrella term for three-dimensional works that aim to transform the audience’s perception of space. Sometimes temporary, sometimes permanent, installation artworks have been constructed in spaces ranging from art galleries and museums to public squares and private homes and will often envelop the viewer in an all-encompassing environment or within the space of the work itself. Installation art developed primarily in the second half of the twentieth century (though there were clear precursors) as both minimalism and conceptual art evolved, culminating in installations in which the idea and experience was more important than the finished work itself. See the artists below, all of whom have made a unique contribution to the dialogue about installation art and how it should be defined.

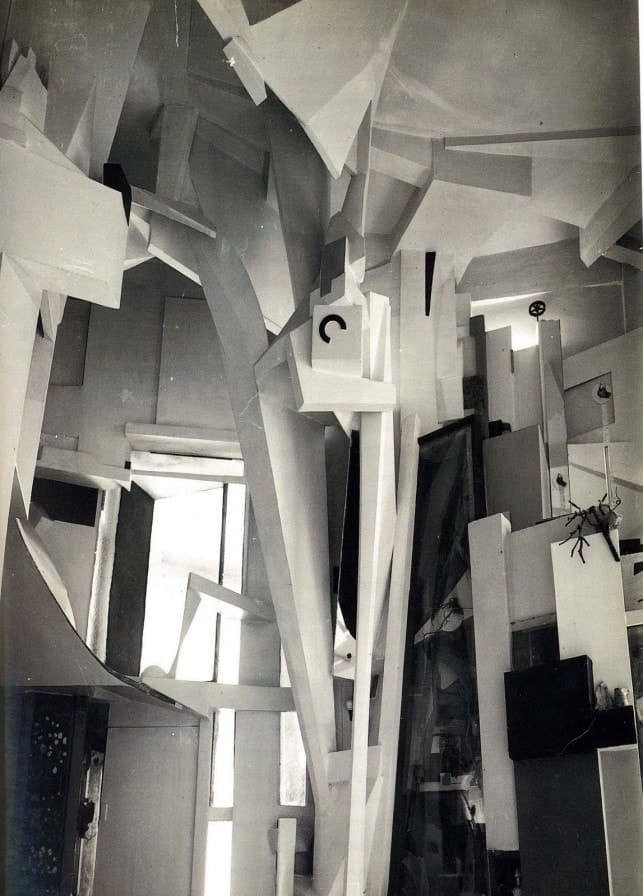

1. Kurt Schwitters

Best known for collages made out of paper scraps, wood, advertisements, and anything else he could get his hands on; 20th century Dada-artist Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948) ultimately turned his own art studio into a collaged art installation. His studio-installation, entitled Merzbau, was borne out of an artistic process which Schwitters explained as both a philosophy and a lifestyle branded “merz”. Merz was a nonsense word that the artist used to describe himself, his life, and his work, meaning that his Merzbau was essentially his merz-building. Over the years his studio took on the form of a walk-in collage, ever-shifting and ever-growing, composed of columns and stalagmites of found objects. Schwitters grew his Merzbau over time, eventually consuming eight rooms in his home in Hannover from roughly 1923 until 1937, when he was forced to flee to Norway to escape Nazi Germany. By 1943, when he was still in exile, the Merzbau was destroyed by an Allied bombing — effectively rendering Schwitters’ living site-specific artwork time-specific as well.

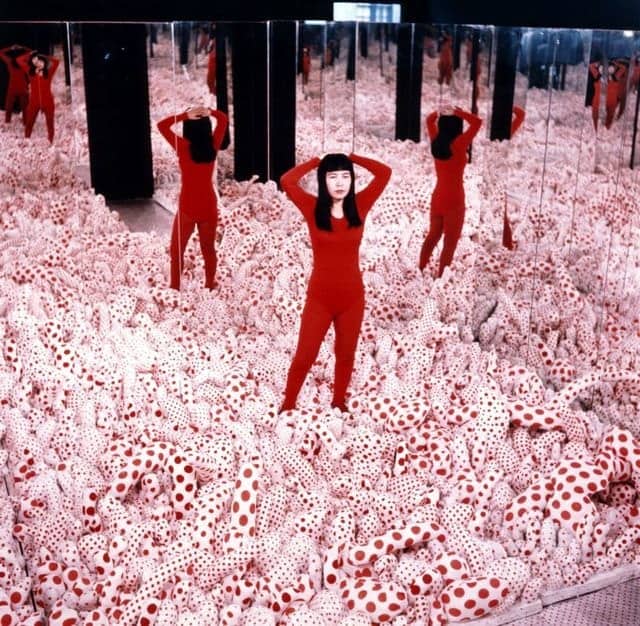

2. Yayoi Kusama

Instantly recognisable and immensely iconic, Yayoi Kusama’s (1929-) series of Infinity Rooms has caught the imagination of her audience since 1965 with her breakthrough Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field. By utilising mirrors as walls Kusama was able to translate the repetition of her earlier artworks into an art installation, a seemingly endless room carpeted with polka-dotted fabric phallic structures. Since 1965 she has created over twenty more distinct Infinity Mirror Rooms from peep-show-reminiscent boxes that audiences view from the outside-in, to larger multimedia installations full of internally-mirrored inflated polka dots. Arguably a fan favorite with museum-going social media influencers are Kusama’s light-filled installations like Infinity Mirrored Room—Aftermath of Obliteration of Eternity that features hundreds of hanging lanterns and paved with water. By tapping into the magic of mirrors, Kusama’s work is able to trick the senses and create poetic art installations that speak to our most human responses, creating environments for existential contemplation.

3. Marcel Broodthaers

For exactly one year, from September 27, 1968 to September 27, 1969 Belgian poet-turned-surrealist artist Marcel Broodthaers (1924-1976) ran a museum, the Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles (translated: Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles). This museum, or rather, art installation, took place in his own home in Brussels and was comprised of several different elements; among which were postcards, a ladder, and numerous empty crates. A tongue-in-cheek statement about authenticity and the role of art and museums in society his Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles ended up travelling to other locations in the form of different departments. Thus bringing the power of the student protests (during which the installation was conceived) throughout Europe.

4. Gordon Matta-Clark

Splitting By Gordon Matta-Clark from GM Clark on Vimeo.

With a deep understanding for architecture’s importance as a reflection of dominant social structures, American artist Gordon Matta-Clark’s 1974 art installation Splitting was an act of urban protest. From March to June of 1974 Matta-Clark used a chainsaw to effectively bisect a New Jersey home acquired by his dealer Holly Solomon and slated for demolition due to land speculation. After the abrupt eviction of the previous owners, Matta-Clark was struck by the hastiness by which they left their belongings, inspiring him to chronical his Splitting from the inside of the home outwards through film. This film shows the fragmentation of the domestic space, with light and air seeping into the rooms through massive architectural gashes in the building, evoking both his own and the universal disintegration of the family. The film and its subsequent books, photographs, and sketches provide documentation of the event as well as acting for and part of the work itself, whilst elements of his ‘anarchitecture’ practice, including large scale building fragments and other detritus were on occasions exhibited as installations in gallery and institutional spaces.

5. Judy Chicago

Brooklyn Museum; Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. (Photo: Donald Woodman)

A monument to women’s history, artist and feminist writer Judy Chicago’s (1939- ) The Dinner Party art installation is comprised of a massive triangular banquet table of thirty-nine place settings. There are 13 settings on each side of the triangle, representing the numbers present at a traditional witches’ coven. Each deeply personalised and characteristic setting honours a historical or mythical female figure: including artists, goddesses, academics, and activists and containing an intricately embroidered runner, chalice, utensils, and china-painted porcelain plates. The plates are yonic in nature, with butterfly-esque forms representing the femininity of the guests of honour at The Dinner Party, and the runners are embroidered at the place settings in the style and technique of that woman’s time in history. The floor on which the table sits honours an additional 999 women, whose names are inscribed in gold on the white tile. Originally a traveling exhibition, the piece was created with the assistance of over 400 volunteers (mainly women) who contributed needlework and sculptural expertise, and can now be found in the permanent collection of the Brooklyn Museum’s Center for Feminist Art.

6. Jason Rhoades

Courtesy the estate, Hauser & Wirth, David Zwirner and lender

Photo: Fredrik Nilsen

Beginning in 1994 Los Angeles-based artist Jason Rhoades (1965-2006) became an installation artist. His first work of installation, Swedish Erotica and Fiero Parts (1994) was comprised of mundane items like cardboard, wood, and styrofoam all painted yellow and assembled to reference the geographical and cultural landscape of Los Angeles. His second work, and arguably one of his most famous, My Brother/Brancuzi was created for the 1995 Whitney Biennial. By juxtaposing his brother’s bedroom with the studio of famous Modernist artist Constantin Brancusi he was able to pay homage to the legacy of Duchamp’s readymades by way of mundane suburban materials. Rhoades created many more art installations throughout his career until his untimely death, pushing the boundaries of social conventions and breaking unspoken rules of public decency.

7. Kara Walker

Best known for her monumental monochrome room-sized silhouettes, American artist Kara Walker’s (1969- ) installation art tackles themes such as gender, sexuality, race, and violence in her work. Her installation art is often accompanied by long, grandiose titles, including Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as it Occurred b’tween the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart (1994) and The End of Uncle Tom and the Grand Allegorical Tableau of Eva in Heaven (1995) and evoke the manner history paintings commemorate notable events. Her installations could be thought of as historical allegories displaying the physical and sexual horrors of slavery and racial persecution, literally engulfing the audience within the narrative as they play out on the walls of the room in which they stand. Walker’s use of the silhouette provides just enough information about her stories, while still being vague enough for interpretation, a reductive form that is reminiscent of the stereotypes about Black Americans that she seeks to unveil.

8. Doris Salcedo

Photo credit Sergio Clavijo

“We have lost our ability to mourn…I want my work to play the role of funeral oration, honoring this life.”

Doris Salcedo, January 2015

Utilising the facade of Bogotá’s Palace of Justice as her canvas, Colombian installation artist Doris Salcedo’s immense work Noviembre 6 y 7 (2002) was an act of remembrance for the 17th anniversary of the seige of the Palace by M-19 guerrillas and the government’s subsequent counterattack in 1985. Focused on acknowledging and remembering violent deaths, Salcedo’s work has highlighted this theme through her work through Colombia’s civil war casualties as well as Chicago’s gun violence victims. Her poetic works are often monumental in size, forcing her audience — which is often comprised of unwitting passersby — to recall these violent acts and engage in the act of mourning.

9. Thomas Hirschhorn

Courtesy Thomas Hirschhorn. Photo: Andy Keate.

“Destruction is difficult. It is as difficult as creation.”

Antonio Gramsci (Italian-Marxist theorist & inspiration for Hirschhorn’s In-Between)

Creating political statements out of mundane, everyday craft materials, Swiss artist Thomas Hirschhorn’s installation art and public pieces are legendary for the amount of attention they receive. Hirschhorn’s sculptural constructions made of mass goods reference the work of radical theorists such as Gilles Deleuze and Georges Bataille’s beliefs on capitalism and consumerism. His works, like Gramsci Monument, a major public installation held at the New York City Housing Authority’s Forest Houses in the Bronx, create alternate dystopian realities for his consumers; holding a mirror up to daily life upon which to reflect and react. His more recent work, In-Between (2015) is informed by his research of bomb-damaged locations around the world; and is an expression of the deep-seated human fascination with destruction and violence that comes from many forms: disaster, structural failure, corruption, fatality, or war.

10. Urs Fischer

Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York

Urs Fischer’s You (2007) brought transformation through destruction to a previously standard New York City gallery space. Fischer tore out the gallery’s concrete floor and filled the void with a pit of dirt, creating a 30-foot by 38-foot crater that measured eight-feet deep within the formerly pristine white-walled gallery. The creation of this foreign, yet immensely natural, landscape provided a jarringly unexpected environment in this context ; an immediate sense of danger coupled with the realisation that where there once was a floor, there is now void. Standing at the edge of the work, the viewer is perched above it and able to take in the vista that both fetishizes and rejects the traditional gallery space through its demolition.

Relevant sources to learn more

Read how stage designer Peter Bissegger tried to recreate the Merzbau

Enjoy more of our “Top 10” series with last week’s article on the Brushstroke