Articles & Features

Les Dîners de Gala: Surrealism on the menu with Salvador Dalì’s cookbook

“We intend to ignore those charts and tables in which chemistry takes the place of gastronomy. If you are a disciple of one of those calorie-counters who turn the joys of eating into a form of punishment, close this book at once; it is too lively, too aggressive, and far too impertinent for you”.

Salvador Dalì

“Conger of the rising sun”: slices of conger eel wrapped in fatty bacon, lettuce, and soya beans; “Thousand years old eggs”: boiled eggs left in the fridge for three weeks in a jar immersed in their boiling water, cloves, sugar, vinegar, Tobasco, lemons, thyme, and tea; “Peacock à l’Impériale dressed and surrounded by its court”: stuffed quails served with a sherry sauce, diced truffles and gelatin; “Toffee with pine cones”: caramel candies with pine nuts. If you think these dishes sound sufficiently whimsical or downright bizarre enough to be surreal, you are definitely on the right path. In fact, they belong to the imaginative and opulent recipe collection Les Dîners de Gala, a cookbook by non-other than Salvador Dalì.

While many artists towards the end of their career tend to write celebratory memories and autobiographies, Salvador Dalì, always swimming against the tide, even at the age of 69, instead decided to publish a cookbook.

As a multifaceted artist, he never allowed himself to be bound by the limits of the canvas, moving from painting and drawing to stage sets and costumes, and from sculpture to cinema and fashion with consummate ease. It is therefore not surprising that his genius, in the constant development of an all-embracing artistic research, found also a means of creative expression in cuisine. His excessively flamboyant gastronomic anthology is an unexpected, though perfect, reflection of both the concept and the aesthetics of Surrealism.

“The jaw is our best tool to grasp philosophical knowledge”.

Salvador Dalì

Salvador Dalì: between Art and Food

Born in the small town of Figueres in Catalonia, Spain, in 1904, Dalì’s passion for food was evident since the early beginning and his family members confirmed his visceral love for all that was edible. In the prologue of his book The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, he wrote: “At the age of six I wanted to be a cook. At seven I wanted to be Napoleon. And my ambition has been growing steadily ever since”. The story goes that as a child, despite being forbidden to enter the kitchens – or perhaps because of it – he would lurk, craving, for hours until the perfect moment to sneak in and steal something delicious under the maids’ amused eyes. Similarly, his artistic talent began to show at an early age: in 1918, the young Dalì had his first public exhibition at the Municipal Theatre in Figueres, making art the only and unquestionable for him to follow.

In 1922, he moved to Madrid to study at the San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts where he became more acquainted with the avant-garde movements, striving to find his own artistic voice between Cubism, Dada, and Futurism. But the most important turning point in his life was the move to Paris in 1926, where he not only discovered Surrealism, whose principles excitingly embraced, but also met Gala, the Russian immigrant ten years older than him, who became his lifelong wife, muse and promoter.

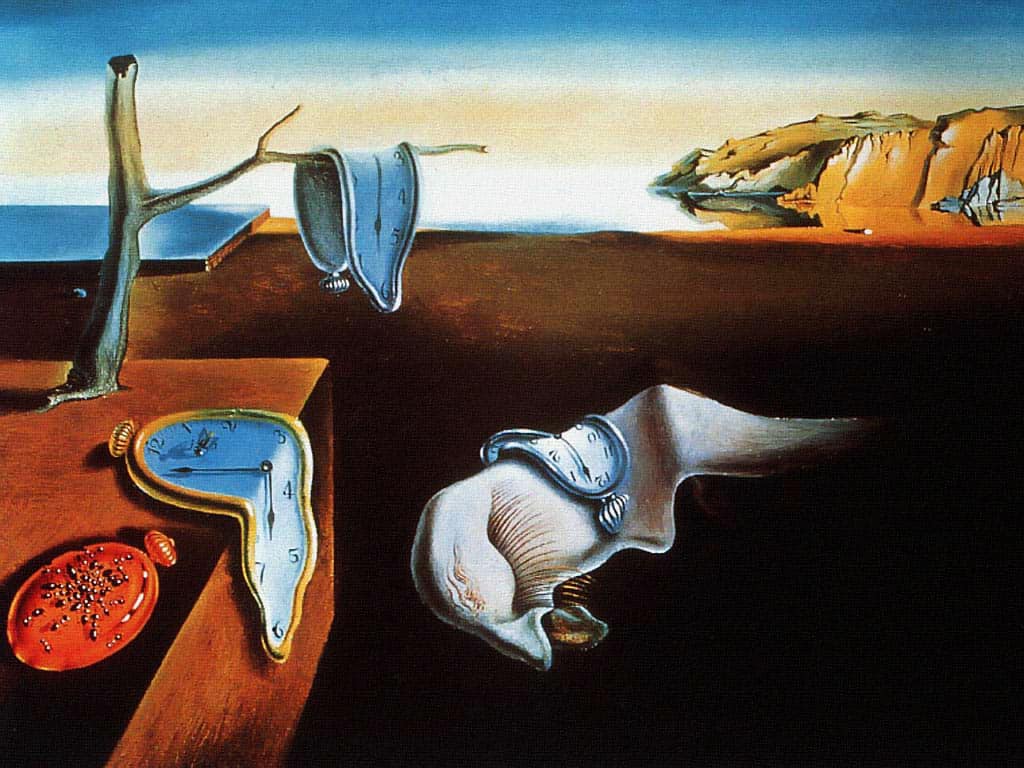

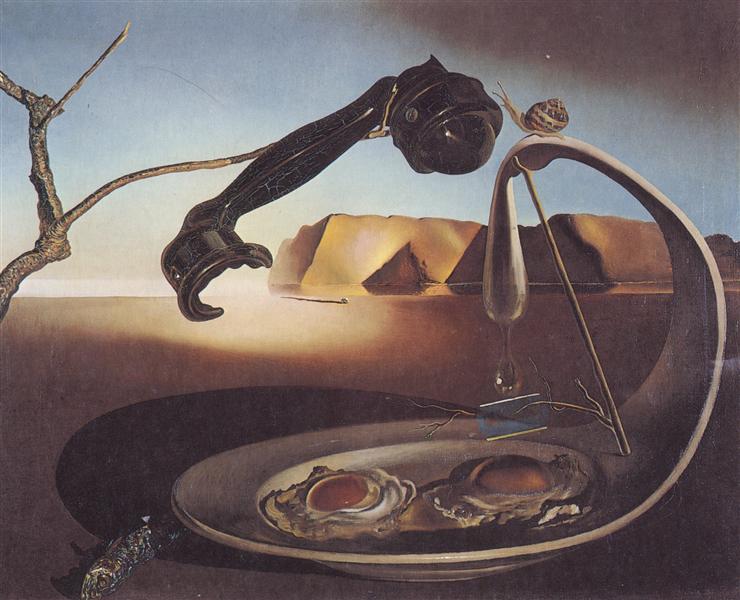

Throughout his entire life, even during the years spent in the United States to take refuge from the Second World War and after the return to Spain, food always remained a source of creative inspiration and pleasure, and food-related symbolism can be found throughout Dalì’s oeuvre. When questioned if in his iconic painting The Persistence of Memory he had interpreted Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity, Dalí replied that the soft watches were rather inspired by the surrealist perception of a Camembert cheese melting in the sun.

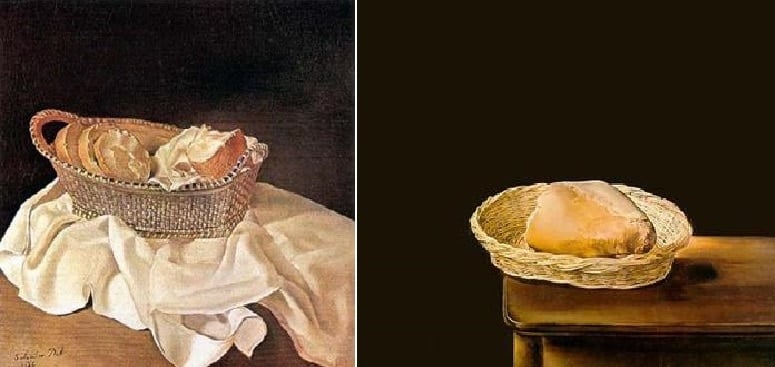

Among his favorite culinary elements, in addition to the legendary lobsters, was a predilection for bread. Even before being familiar with Surrealism, he painted The Basket of Bread explaining that “by the power of its density, the fascination of its immobility, creates the mystical, paroxysmic feeling of a situation beyond our ordinary notion of the real. We are at the borderline of dematerialization of matter by the sole power of the mind“. After almost twenty years he returned to the subject, creating another version with the basket placed more precariously at the edge of the table: “Bread has always been one of the oldest subjects of fetishism and obsession in my work, the first and the one to which I have remained the most faithful“.

Bread loaves are an ever-present component of his work, especially the French baguette, so much so as to enable a theory of a “bread revolution” aiming to transform the symbol of nutrition into a useless aesthetic object. When, in 1934, he travelled to New York for the first time, he asked the ship’s cook to bake him an over-sized baguette and, once in the harbour, promptly walked down the gangplank waving it in the air – a performative gesture that, much to his chagrin, went completely unnoticed.

Another emblem of the Dalinian universe was the egg. He was convinced that he could perfectly remember his formative life inside his mother’s womb: this lucid memory coincided, in his mind, with the impressive vision of two magnificent and phosphorescent fried eggs oscillating together with him in the amniotic fluid. This belief led him to the exaltation of the egg as a uterine symbol. When, at the age of 80, he designed his own museum – where he is now buried in a crypt – as a great surrealist object, he had the entire outer perimeter covered with thousands of representations of the typical Catalan bread alongside the placement of dozens of giant eggs.

A glimpse into Dalì’s cookbook: Les Dîners de Gala

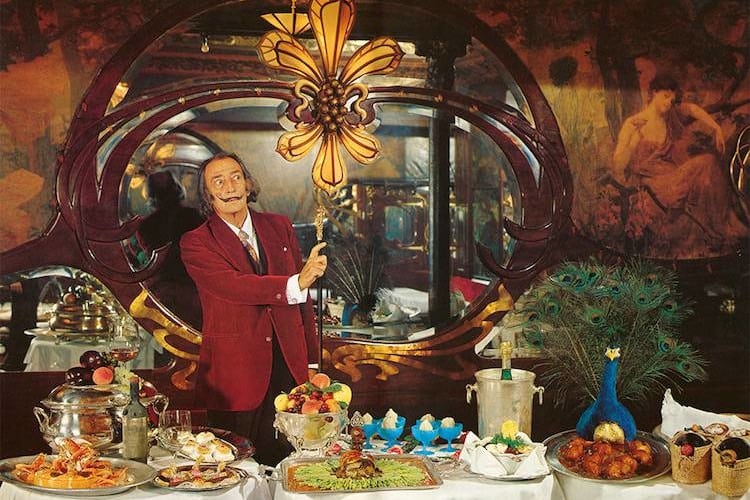

Along with his wife Gala – whose name proved to be quite contextually appropriate – Dalì used to throw lavish dinner parties that were the stuff of legend: opulent banquets that were widely attended by celebrities, where guests wore bizarre costumes, wild exotic animals – especially monkeys – roamed freely in the rooms, and food was served in satin slippers.

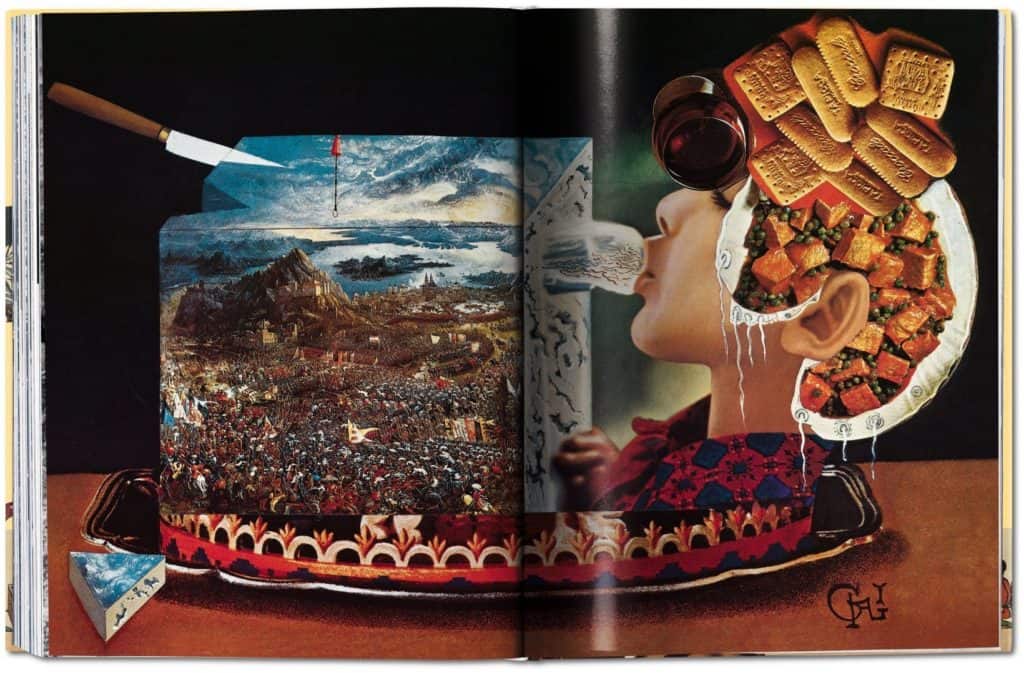

In his cookbook Les Dîners de Gala, Salvador Dalì perfectly captured the essence of such sumptuous feasts. The artist interpreted old-school French gastronomy with meals by leading Parisian chefs from stellar restaurants as Lasserre, La Tour d’Argent, Maxim’s, and Le Train Bleu (some are still served today), enriched by Dalí’s imaginative illustrations and photographs, as well as his extravagant musings on subjects such as dinner conversation.

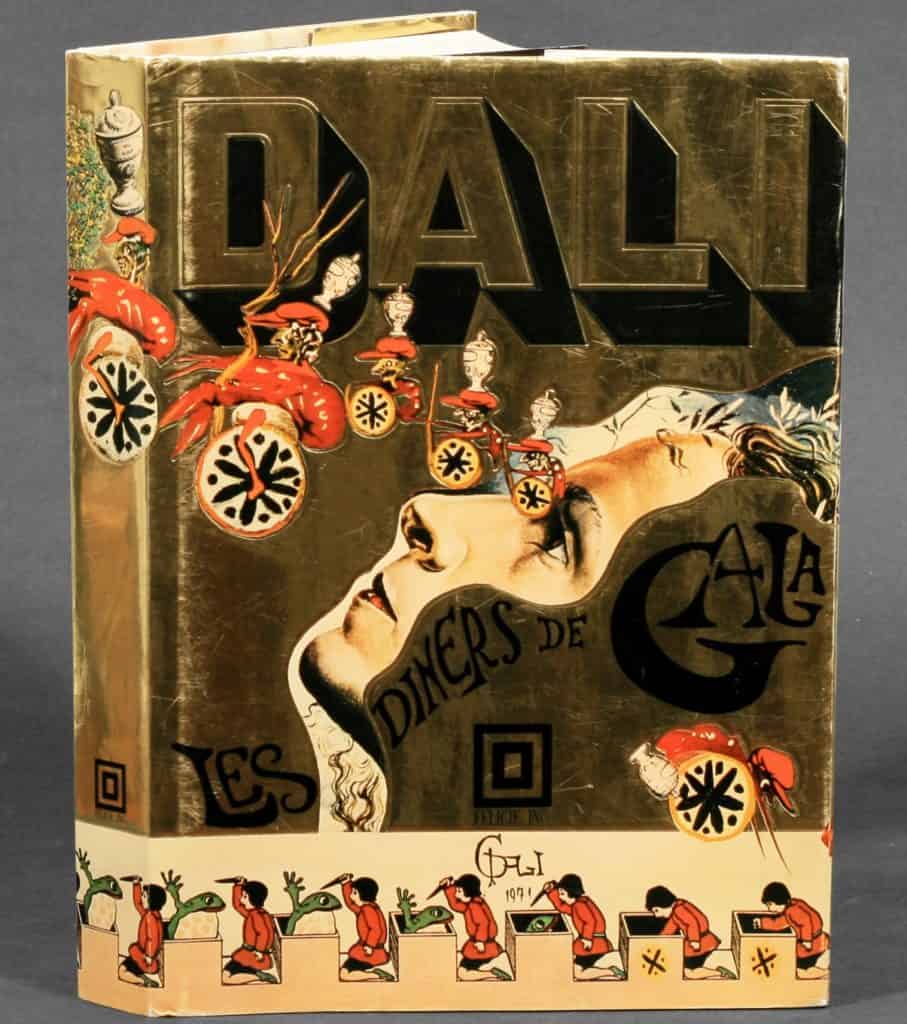

Dalì’s cookbook, published by Taschen in 1973, was printed in a limited production of only 400 copies and which today are sought after collector’s items. In 2016 the publishing house released a commemorative and re-edited version, making this exceptionally rare book available to a wide audience.

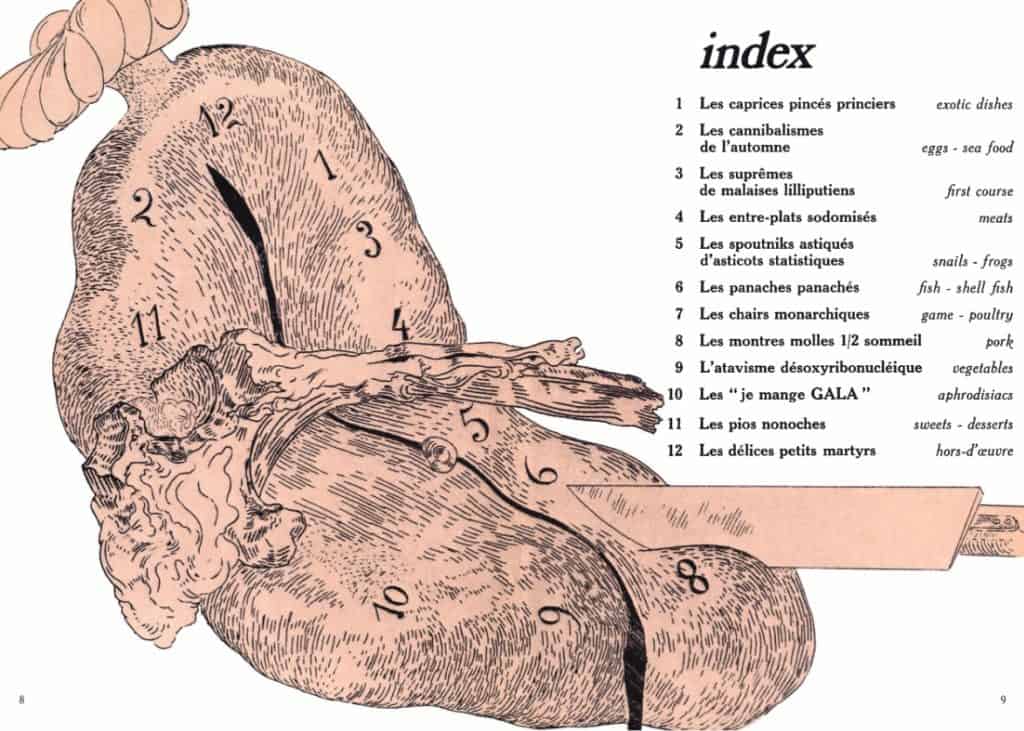

The 136 recipes of this collection are divided into twelve chapters corresponding to different meal courses, from The caprices pincés princiers – literally “The princely pinched caprices” – that is to say exotic dishes, to Les dèlices petits martyrs – “The delicious little martyrs” (appetisers), passing through Les suprêmes de malaises lilliputiens – “The supremes of Lilliputian discomfort” (first courses), and Les “Je mange Gala” – “The ‘I eat Gala’” (aphrodisiacs).

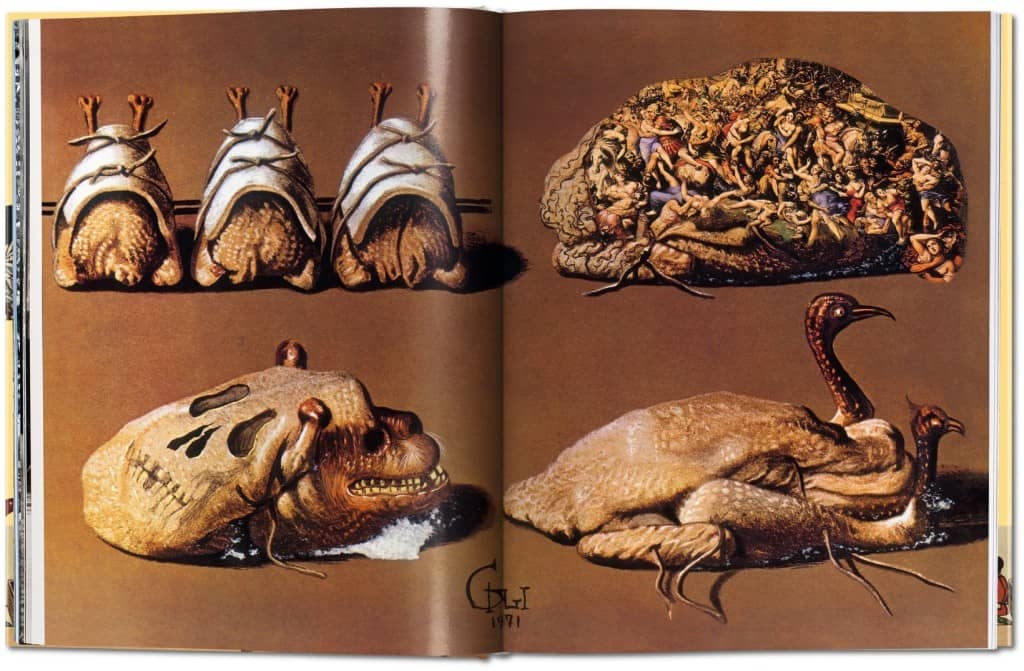

Dalí’s strangely artful depictions of culinary worlds that fill the pages follow the Surrealism principles in different ways. Many liberally employ the use of collage: in one illustration, a disembodied head with biscuits for hair and a fringe made of a jar of jam sits on a platter alongside a large cube of blue cheese, the sides of which show a crowd in front of a mountain. But this is true also in terms of ideas, in particular the concept of displacement is adopted (selecting an object and then removing it from its usual context): only Dalì could bring together a swan and a toothbrush on a pastry case.

The contradiction between hard and soft, often recurring in Dali’s work, is represented in this case by different ingredients: on the one hand, the hated “soft” spinach: “that detestable, degrading vegetable called spinach. (…) I only like to eat what has a clear and intelligible form”; on the other, the beloved “hard” crustaceans: “the opposite of shapeless spinach is armour. I love eating suits of arms, in fact, I love all shellfish (…) food that only a battle to peel makes it vulnerable to the conquest of our palate”.

The whole concoction is an entertaining visual feast that contains the key to plenty of delicious meals, but the audacious illustrations that fill the book, with paintings of blood-red meat cuts, implausibly tall shrimp towers, and scenes of cannibalism, are the indubitable stars of Salvador Dalì’s cookbook. So much so that one often needs reminding that this is, in fact, an actual cookbook: despite the fact that many require advanced technical skills and an extremely well-stocked pantry of lavish ingredients.

Ultimately, this book is delicately balanced between sensuousness, eccentricity and the grotesque, and is at once an artwork and practical guide for the both the most daring of eyes and palates.

Relevant sources to learn more

Salvador Dalì, Les dîners de Gala, Taschen, 1973 (Re-edited in 2016)

Salvador Dalì, Les Songes Drolatiques de Pantagruel, 1973. Litographs included in “Les dîners de Gala” (Edition: 111/250)

Dalì Theatre-Museum in Figueres, Spain