Articles & Features

Artistic Collaborations: Elsa Schiaparelli & the Early 20th Century Avant-garde

By Benedetta Ricci

” I gave to pink the nerve of the red, a neon pink, an unreal pink.”

Elsa Schiaparelli

There are aspects of contemporary life that we take for granted as if things had always been as we now know them. For example, it is natural for us to consider our way of dressing as an expression of ourselves and our personality, and we are always amazed but not totally surprised when seeing fashion shows that resemble theatrical performances, with excessive fabrics, loud and vigorous music, and incredible set designs. However, it hasn’t always been like that, and today’s fashion owes a great deal to the legendary stylist Elsa Schiaparelli. Nonetheless, her extraordinary work would not have been the same without her close collaboration with the most influential avant-garde artists of the time, crossing art styles and movements. This edition of the “Artistic collaborations” series explores how, in 1930s Paris, this collaboration pushed the barriers between fashion and art giving rise to an unparalleled synergistic and cultural relationship.

“In difficult times, fashion is always outrageous”

Elsa Schiaparelli

Elsa Schiaparelli

Born in Rome in 1890 to a wealthy family of aristocrats and academics (her mother was a descendant of the historical Medici family), Elsa Schiaparelli – “Schiap” as she was best known – grew up in an erudite and religious environment, too conservative to embrace her innate imaginative capabilities, extravagance, and desire for freedom.

Berated by her mother for being bizarre and homely looking, especially compared to her angelical sister, Elsa decided to distract attention from her self-conscious lack of conventional beauty by turning her own face into a heavenly garden full of flowers. She put flower seeds in her ears, mouth, and nose, convinced that her body warmth would make them grow quickly. On this occasion, she almost suffocated, but she never lost the inclination to subvert notions of beauty with irreverent and whimsical ideas. “If I cannot be the most beautiful, then I will be the most extravagant” was a dictum she adhered to her entire life.

After studying literature and philosophy, at the behest of her family, she chased a much sought after emancipation by escaping first to London and then to New York together with her first husband, a supposed esoteric theosophist mainly interested in her dowry.

In 1922, with a failed marriage behind her and a young daughter, Elsa moved to Paris where her journey into fashion would soon begin.

It was in Paris that Elsa met the couturier Paul Poiret, the stylist who freed women from the corset, an encounter that became the key and which changed her life. She became his apprentice and started designing oneiric and excessive clothes.

In only five years, with no formal training, she was able to open her first atelier and design a collection of knitwear using a special double-layered Armenian stitch with cubist, primitivist and surrealist inspiration. It was a piece from this collection that secured her fame, a trompe l’oeil sweater with a pattern reproducing a scarf wrapped around the neck.

Success was not long in coming and quickly crossed the ocean. US Vogue, featuring her work, described Schiaparelli as “responsible for the feeling of spontaneous youth that has crept into everything”. In a short time, she opened a shop in Paris that swiftly became the meeting point of the most innovative and radical Parisian artists, in turn outfitting the world’s most glamorous women, from Greta Garbo, and Marlene Dietrich to Joan Crawford, Katharine Hepburn, and Zsa Zsa Gabor.

With her visionary approach, she broke every fashion rule. Wide draping and numerous brooches, initially meant to fix the lack of technical expertise in her garment engineering, became a way to enable freedom of movement, to enhance the volumes as well as a means of self-expression through exaggerated accessories. Buttons turned into mermaids, jewellery into insects. The skirt merged with the trousers in the creation of the so-called “skort” (or divided skirt), which was immediately used by tennis players, and not without scandal. Fabrics that never matched before were combined, the fancy silk met the humble wool, and innovative materials such as artificial fibres were introduced.

Elsa Schiaparelli, the only rival of industry titan Coco Chanel, went beyond the status quo and gave the women of the time both a way to adapt to the practicality of modern life and a means to define themselves.

Avant-garde Art in the Early 20th Century Paris

During the first decades of the 20th century, the French capital had become the international nexus for avant-garde art, the ideal environment for innovation and experimentation of every kind. Numerous artists migrated to the city attracted by its vibrant and cosmopolitan life. Districts such as Montmartre and Montparnasse attracted numerous artists with different styles and backgrounds but united in their radical defiance of academicism. Cubists, Surrealists, Dadaists, and other rather uncategorised artists such as Marc Chagall, Amedeo Modigliani, and Alberto Giacometti were active protagonists of this fertile cultural scene.

Elsa Schiaparelli & the Avant-garde

Schiaparelli’s first encounter with the Avant-garde happened whilst aboard her first transatlantic crossing to America in 1916, where she met the writer Gabrielle ‘Gaby’ Picabia, wife of the Dada artist Francis Picabia. Once in New York, the couple introduced her to their artistic circle, including Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp, Alfred Stieglitz, and Edward Steichen. Her fanciful powers of imagination, along with her interest in spiritualism, translated into an immediate affinity for the Dada and Surrealist leanings of the group. It was following their steps that Elsa decided to move to Paris after the finalisation of her divorce.

She became swiftly immersed in Parisian artistic life, not only drawing inspiration from the most influential art movements of the time but an integral part of them.

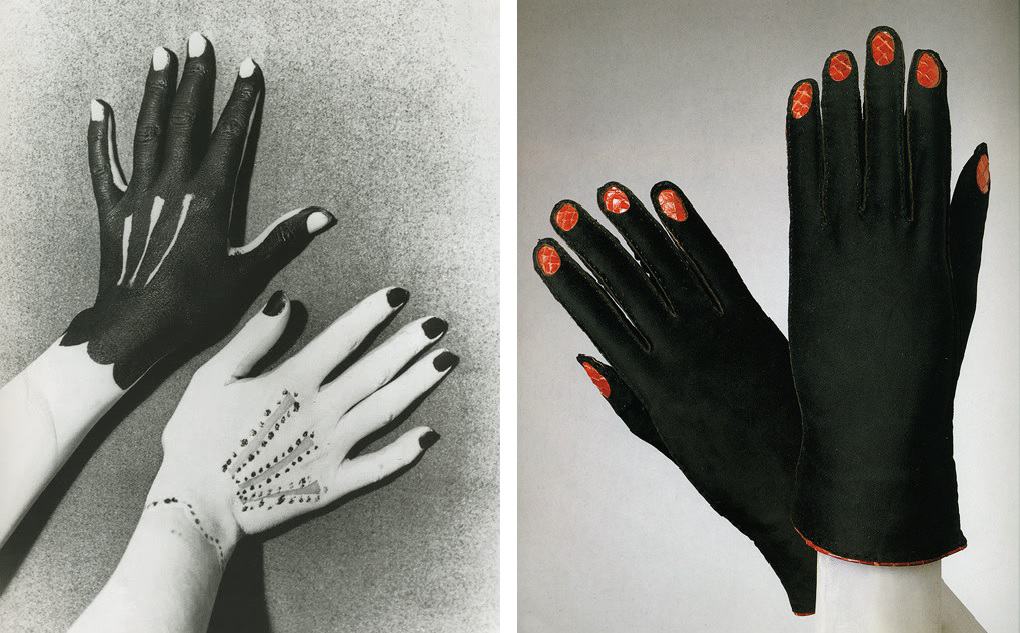

Inspired by the work of Pablo Picasso and Man Ray which depicts painted hands that look like gloves, Schiaparelli designed a pair of gloves to look like hands. It was a Picasso painting used to illustrate the frontispiece for her 1954 autobiography, Shocking Life.

Her collaboration with Salvador Dalì produced some of the most humorous and absurd results. United in the desire to shock and amuse at the same time, they created pieces that are still the cornerstones of fashion design: the Lobster dress featuring a motif dear to the artist, the Shoe-hat that plays with the surrealist idea of displacement – selecting an object and then removing it from its usual context – and the Skeleton dress, among others. Schiaparelli also collaborated with Jean Cocteau, Méret Oppenheim, and Alberto Giacometti.

With the same original and irreverent approach that Schiaparelli faced fashion, she also revolutionised the fragrance world with her perfume, for which she chose the explicit name Shocking! , which in turn made ‘shocking pink’ her signature colour.

The glass bottle of her popular perfume, designed in collaboration with the surrealist artist Leonor Fini, provocatively reproduced a female torso, shaped on the curves of the American actress and sex symbol Mae West, and topped off with a heady bouquet of vibrant flowers. Eventually, Schiaparelli managed to grow all aspects of her creative life into the heavenly garden she once coveted as a young girl for her own visage.

Relevant sources to learn more

Take a look at other articles in our Artistic Collaborations series:

Martha Graham & Isamu Noguchi

Pablo Picasso & Gjon Mili

Keith Haring & Grace Jones

You may also like:

Paul Poiret: Life and Designs of the King of Fashion

Enjoy Google Arts & Culture exhibit “Schiaparelli and Surrealism”

Today’s Maison Schiaparelli