Articles and Features

Lest We Forget.

Charlotte Salomon’s Life? Or Theatre?

“And with dream awakened eyes she saw all the beauty around her, saw the sea, felt the sun, and knew she had to vanish for a while from the human surface and make every sacrifice in order to create her world anew out of the depths.”

Charlotte Salomon

Every year on January 27, the entire world commemorates the memory of the victims of the Holocaust on the anniversary of the liberation of the Nazi Concentration and Extermination Camp of Auschwitz-Birkenau by Soviet troops on January 27, 1945.

The International Holocaust Remembrance Day, proclaimed in November 2005 by the United Nations General Assembly, reaffirms the unwavering commitment to counter antisemitism, racism, and other forms of intolerance.

On this occasion, we pay tribute to the tragic life and ground-breaking art of Charlotte Salomon, killed in Auschwitz in 1943, aged twenty-six.

In a burst of creativity in the early 1940s, she was able to turn her life, marked both by personal tragedy and dramatic political events, into an intimate total work of art of original nature: Leben? oder Theater? – Ein Singspiel (‘Life? Or Theatre? – A Musical Play’).

Her monumental work, often regarded as an early graphic novel of sorts, today still speaks powerfully and remains as an ode to the will to survive.

“The war raged on and I sat by the sea and saw deep into the heart of humankind.”

Charlotte Salomon

Charlotte Salomon’s Life

Born in Berlin in 1917 to a wealthy German Jewish family, Charlotte Salomon grew up in an erudite environment in the elegant suburb of Charlottenburg, her household mingling with leading lights of the calibre of Albert Einstein, Erich Mendelsohn, and Albert Schweitzer. Her world, however, would soon start to crumble. In 1926, her mother died while convalescing at her parents’ house, and in 1933 Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor; nothing would ever be the same again.

Both Charlotte’s father and his new wife, Paula Lindberg, lost their jobs – as a university professor and concert alto singer, respectively. Charlotte, however, was admitted to the prestigious Academy of Arts in Berlin, where she studied painting for two years until it was too dangerous to remain.

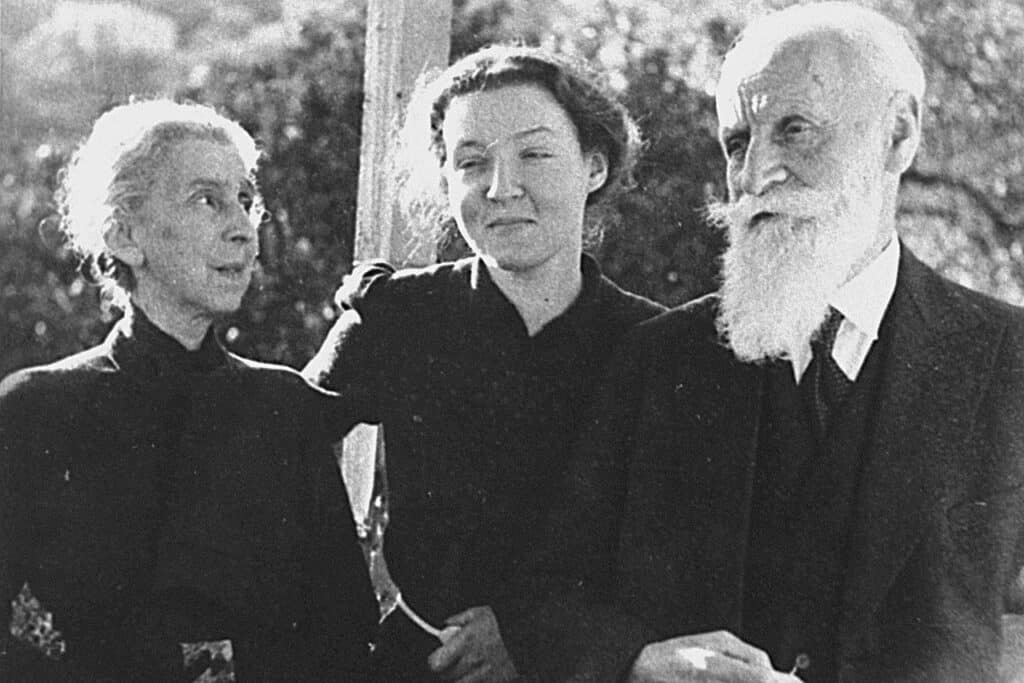

In 1938, following the tragedy of the Night of Broken Glass, her father’s detention and torture, Charlotte fled Germany to southern France, where she joined her maternal grandparents.

The old couple had taken refuge in L’Ermitage, a villa owned by a millionaire American woman of German parentage named Ottilie Moore.

The woman, thanks to her father’s fortune had moved to Villefranche on the Côte d’Azur in 1929 and later converted her luxurious property into a shelter and hiding place for Jewish children and pregnant women.

Despite the relative tranquillity of the new context, the string of horrors in Charlotte Salomon’s life was not over: following the outbreak of the Second World War, her grandmother – who Charlotte had found deeply depressed – after a first failed attempt, took her own life, leaving the 21-year-old Charlotte alone with the both mentally and physically abusive grandfather.

The hatred for the man was such that after they were interned by the French authorities for several weeks in the concentration camp of Gurs, while looking back to the night spent in the crowded train to the camp, she commented: “I’d rather have ten more nights like this than a single one alone with him.”

The trauma of deportation added to another experience – even more shocking, to Salomon – as her grandfather revealed the young woman a dark, unbearable truth: their family held a long-concealed history of suicide and her grandmother was, in fact, the eighth suicide victim in the family over three generations. Charlotte’s aunt, whom she was named after, had left the family home in Berlin one night in 1913, walked twenty-one miles and drowned herself in a lake; Charlotte’s own mother, Franziska – who she had always believed to be dead of influenza – in actuality had jumped out of the window, just as her mother would do in France fourteen years later.

Living in the constant fear of going mad herself, Charlotte Salomon consulted the local doctor, Dr Georges Moridis and, by his advise, began to paint.

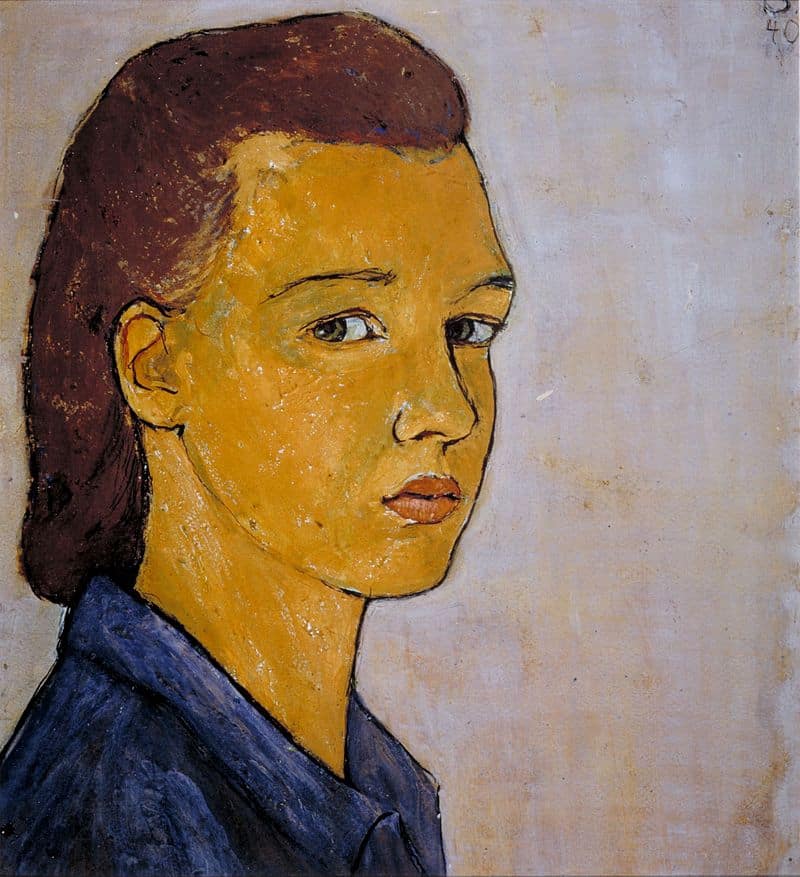

Finding in art the antidote to death and sorrow, Charlotte turned the grimness of her family autobiography in all its misery into her life’s monumental masterpiece: Leben? oder Theater?

“My life began when I found out that I myself am the only one surviving, I felt as though the whole world opened up before me in all its depths and horror,” she wrote. “I will live for them all.” She took a small room at the Hôtel Belle Aurore in Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat and retreated there in almost complete isolation, painting frantically, if not obsessively, for months.

In 1943, the artist married Alexander Nagler, a Jewish Romanian refugee, in doing so, dangerously producing legal evidence of their existence and address.

As the Nazis intensified their house to house search for Jews in southern France, Salomon wrapped Life? Or Theatre? in brown paper, addressed it to Ottilie Moore, and then handed it to her doctor and trusted friend Georges Moridis: “Keep these safe, they are my whole life.” In September that year, the couple was dragged from their house and transported to the camp of Drancy. Salomon was then deported to Auschwitz, her life tragically cut short in the gas chambers upon her arrival. It was October 10, 1943; Charlotte Salomon was twenty-six years old, and five months pregnant.

Life? Or Theatre?

Often overshadowed by Charlotte Salomon’s dramatic fate, Life? Or Theatre? has recently come to occupy a place among masterpieces of modernist art.

The work is a massive corpus of nearly eight hundred page-size gouaches and hundreds of transparent overlays with vignettes, sarcastic comments and chorus to sit on top of the paintings.

Salomon herself defined the work as a singspiel – a traditional German music form which can be roughly described as a musical play. Images and texts are, in fact, accompanied by directions for music, as a modern soundtrack ranging from Nazi marching songs to Schubert lieder and extracts from the music of Mozart and Mahler in a genre-bending creation. Combining historical events, personal memories and imagination, Salomon retraced her dark family history from 1913 to 1940: from her aunt’s suicide to the moment she decided to paint her life, rather than to take it.

The work is structured in three parts: the prelude, the main part and the epilogue and is narrated in the third person by Salomon’s avatar, ‘Charlotte Kann’.

The characters – Charlotte’s family members – are listed at the start of the series, as in a theatre programme. “I became my mother, my grandmother […] I was all the characters who take part in my play. I learned to travel all their paths and became all of them,” she wrote.

Although Life? Or Theatre? offers a unique perspective on the extreme historical circumstances in which the work was produced, the collection is not about the war or the Holocaust, but rather an intimate and desperate act of self-expression on the themes of love, life, and death by an anguished individual who saw in art the redemptive power she could not find elsewhere.

Almost obsessively created, the work does not lack complexity in terms of composition, process, and materiality. On the contrary, it shows a rich personal narrative and it is imbued with cultural references that are both musical and artistic – from the Old Masters to Munch and Van Gogh – but also cinematic, in particular reminiscent of Fritz Lang’s pioneering films.

With its original, well-thought compositions, and intense colours, Life? Or Theatre? is deeply engaged with the art of the time and is immensely valuable both in its entirety and its single components.

Recognition

Ottilie Moore, to whom Life? or Theatre? was addressed, never managed to see the work, as she had fled to New York.

Salomon’s masterful collection spent the remainder of the war in Moridis’ safekeeping instead, until Salomon’s father and stepmother – who had survived the Holocaust by escaping Westerbork concentration camp and hiding in Amsterdam – learned of the work’s existence and travelled to Villefranche to receive it from Dr Moridis’ hands.

First published in 1963, Charlotte Salomon’s life’s work is still relatively little known but is drawing more and more attention from both the public and the critics, especially since the publication, in 2014, of the best-selling novel Charlotte by David Foenkinos which brought the story to the public eye.

The book reached almost cult status, to the point that not even the release of a previously unknown – and rather shocking – letter by the Parisian publisher Le Tripode succeeded in overshadowing the novel’s – and consequently Salomon’s – fame.

The letter is now part of the new edition of Life? or Theatre? and consists of a nineteen-pages confession of murder in which the artist documented the homicide of her abusive grandfather by serving him a “Veronal omelette”. “I knew where the poison was,” she wrote. “It is acting as I write. Perhaps he is already dead now. Forgive me.”

With only a few exceptions, Salomon’s body of work is held at the Jewish Historical Museum in Amsterdam, where her parents donated it in 1971.

Being very fragile, Life? Or Theatre? is not on display permanently, with only six gouaches on display in rotation.

On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the artist’s birth, the museum mounted a retrospective dedicated to her artistic legacy that has travelled to diverse institutions across the world. Following the exhibition’s success, the museum has also decided to hold a series of shows, each meant to illuminate a different aspect of Salomon’s oeuvre. The first in the series was Charlotte Salomon in close-up, the influence of cinema on Life? or Theatre?

Although imbued with illness, suffering and death from the start, Salomon’s utterly original work has inspired artists, film-makers, writers and choreographers to make creations of their own. Among the others, Dutch director Frans Weisz realised a feature film and a documentary, in 1981 and 2011 respectively.

In spite of the personal and historical horrors, the final pages of Life? or Theatre? are decidedly optimistic, ultimately sending a powerful message of hope and life.

In Salomon’s own words: “She found herself facing the question of whether to commit suicide or to undertake something wildly extraordinary.” Undoubtedly, she chose the latter and succeeded.