Articles and Features

Lost (and Found) Artist Series: Euan Uglow

By Shira Wolfe

“Uglow’s radical and experimental oeuvre can easily match the work of his celebrated compatriots Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud. Uglow however, liked to distance himself from the art world – he eschewed stardom – and primarily built a great reputation as a true artists’ artist”. – Creative director of Museum MORE, Ype Koopmans

Artland’s Lost (and Found) Artist Series focuses on artists who were originally omitted from the mainstream art canon or were somehow largely unknown or invisible for most of their careers. We feature British artist Euan Uglow (10 March 1932 – 31 August 2000), whose art was long undervalued by art-world professionals and museums. Today, he is a source of inspiration and a point of reference for many contemporary figurative artists.

Who Was Euan Uglow?

Euan Uglow was born on 10 March 1932 in London. Some of his most impressive works are his evocative nudes, while other distinctive pieces are his still life paintings.

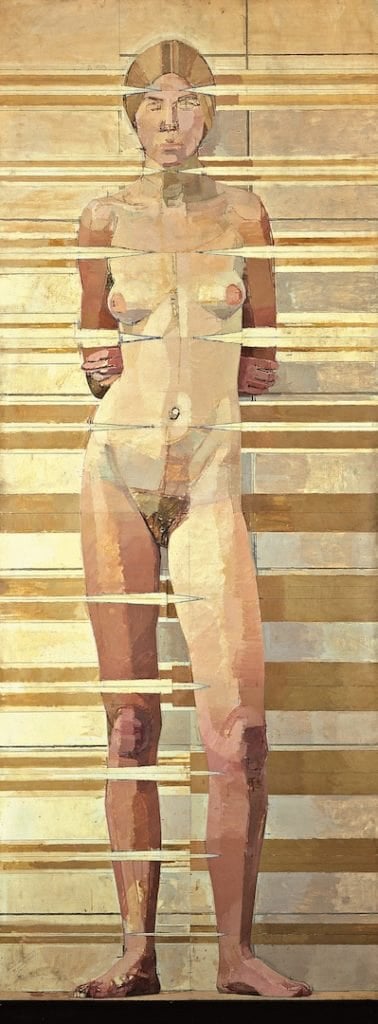

Uglow began his artistic career in 1948 at the age of 15, when he was accepted to the Camberwell School of Arts. It was there that he first met his professor William Coldstream, who was to have a profound influence on the young artist. Coldstream started teaching at the Slade School of the Arts the following year, and Uglow started studying there in 1951. Some of his earliest paintings experiment with systems of representation. “The Musicians” (1953) focuses on perspective, while “Nude, From Twelve Regular Vertical Positions From the Eye” (1967) is about eliminating perspective.

It took Uglow eight years after finishing art school to sell a painting, and in the meantime, he worked various part-time teaching jobs, among which was a position at Slade from 1961. Uglow was a shy artist, who tended to avoid publicity and honours. He refused an offer to become a member of the Royal Academy in 1961, though he did become a trustee of the National Gallery in London in 1991.

The Style and Approach of Euan Uglow

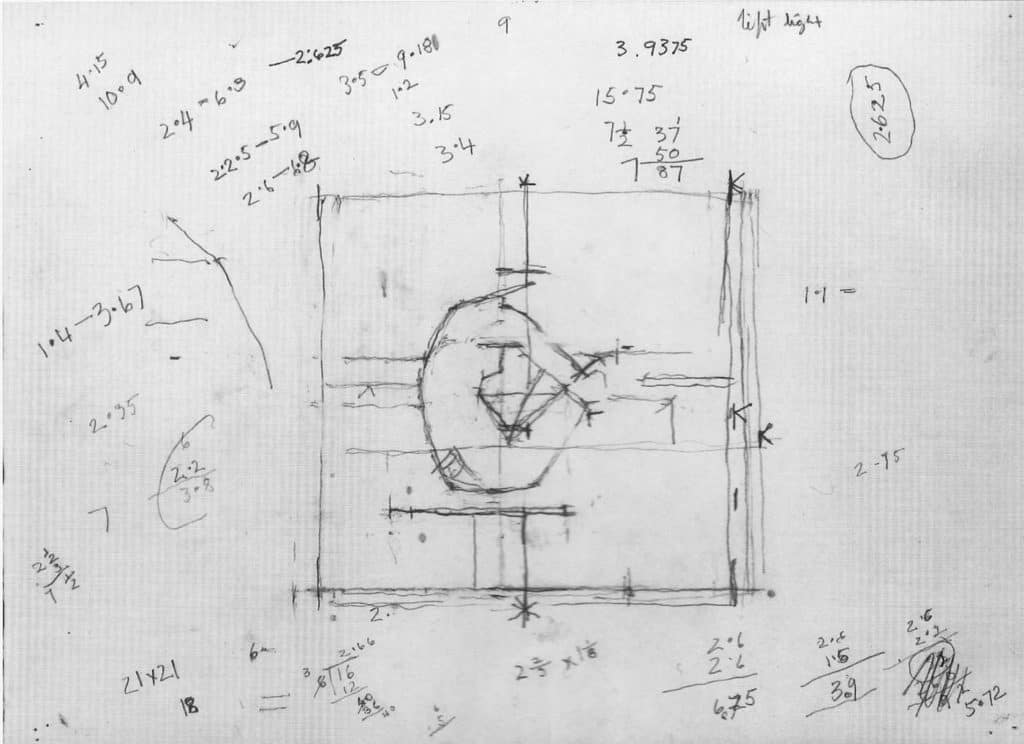

Uglow inherited Coldstream’s system of measurements and marking, depicting his nudes and still lifes almost sculpturally and almost always working from direct observation. His attitude towards mark making and surface owed to the Old Masters, but also to William Coldstream, Piet Mondrian, and American Abstract Expressionists Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman. The measuring marks in Uglow’s paintings are a distinctive feature of his work. The marks were meant to help measure between the different points, to refer to the classical golden section (ratio), and to maintain perspective and proportion, and Uglow liked to keep them visible in his paintings because he never knew when he might need to refer to them again. Due to his meticulous method of building compositions and execution of his painting, it could take Uglow years to finish one painting, and could take as long as 45 minutes to find the perfect position for his models. Oftentimes, his models would sit for him for so many years that they would go through countless life events during this period, from marriage to divorce, for example. This slow approach resulted in an exceptionally small output, at times no more than 3 or 4 canvases a year.

Uglow was known for his rigorous self-imposed rules and personal structure so that he was able to focus almost exclusively on his painting. He only painted during the days, and would draw at night since the light was different then. He would later amend this rule when he started his “Night Painting” series.

“I take measurements so that the subject has a real link to the rectangle; it also gives me freedom to make a whole surface… I’m painting an idea not an ideal. Basically I’m trying to paint a structured painting full of controlled, and therefore potent, emotion.” – Euan Uglow

Euan Uglow’s Nudes

Uglow was notorious for requiring his models to take on difficult poses, and his models were often required to commit to years of posing since it took him so long to complete a painting. The diverse array of poses show the beauty and versatility of the female figure, while the structured nature of the paintings reflects Uglow’s dedication to a meticulous approach to painting from life.

Uglow was fascinated with painting an idea, creating highly rigourous paintings filled with controlled, pent-up and therefore potent, emotion. But despite the unmistakable precision, his painstakingly calculated and deftly deployed brushstrokes seduce the eye each step of the way across the canvas. In order to balance the weight of his figures and to achieve harmony, Uglow would frequently place differently-coloured planes in his compositions.

Still Life Paintings

Due to Uglow’s slow painting approach, his still life set-ups faced the problem that his subject-matter might rot before he could finish the painting. Therefore, when it came to his still lifes, Uglow would say that he was in a “state of emergency,” and work furiously in order to finish his paintings before his subject matter had changed too much.

Some of Uglow’s still lifes contain deep stories related to Uglow and the people closest to him. “Mimosa” (1970-1971), for example, is a painting of flowers from his friend’s mother’s funeral. “A Tongue for Rudi” (1997) was done in memory of his friend Rudi Nassauer, who liked eating boiled tongue.

The “Night Painting” Series

In a later phase in his life, Uglow allowed himself to break his self-imposed rule of painting at night, and started a series of “Night Paintings,” paintings of figures he would do in his studio at night. He did, however, give himself some limitations to work with. Initially, he limited his palette to yellow ochre, cold black, and white. Later on, he added scarlet vermillion. He painted this series in a more rapid style than usual. The distinctive colour-use resulted in a very particular colouring of his figures, capturing the fluorescent lighting on a dark night. These paintings are incredibly haunting, evocative pieces recalling at times the loneliness of the solitary human body, at other times the sense of freedom and strength human beings can experience in their solitude.

Euan Uglow’s Drawings

Drawing was also an essential part of Uglow’s process; in fact, it has been said that it lies at the very heart of his artistic process. In Uglow’s own words: “Drawing is the most immediate way of making your ideas, sensations, and information explicit.” Uglow’s drawings are compilations of marks, dashes and dots. Some of his drawings would start with an idea, while others were more a process of uncovering. For Uglow, drawing helped him to discover the details, the weight, and the shape of a body or object. Often, his drawings were exploratory studies intended “to see what a form is doing.”

Euan Uglow’s Exhibitions and Recognition

Uglow lived by the motto that no one could be too much of a perfectionist. He had an incredible work ethic, spending most of his time in the studio, and was skeptical about self-promotion regarding his career. Therefore, his talent and unique style were never matched by the amount of recognition or acclaim he would receive receive. Most of his shows were presented by his dealer William Darby in his Browse & Darby Gallery in London. Darby also organised a show at Salander-O’Reilly in New York in 1993. In 1974, a national tour started at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, and Uglow’s next Whitechapel show was in 1989, when he showed 32 nudes. He also showed in the US, Jerusalem, and throughout England. Uglow participated in landmark exhibitions such as “Eight Figurative Painters” at the University of Yale Center for British Art in 1981, and in “The Hard-Won Image” at the Tate Gallery in 1984.

Since Uglow’s untimely death in 2000 at the age of 68, he has become more and more widely recognised as a radical and inventive painter. His poetry of precision remains a great inspiration to many contemporary artists.

Recently, the Dutch museum MORE (Museum for Modern Realism) presented an exhibition dedicated to Euan Uglow (26 May – 1 September 2019), showing his entire oeuvre for the first time outside of the United Kingdom. According to the museum curators, Uglow’s ambition with each new painting was to achieve absolute perception. He would say: “They’ve got to sing better. Each bit of colour has to ring clearly.”