“There was no question with him that the talent and the dedication were real. However, the main thing I remember about him was how terribly intense he was – a combination of extreme intensity and shyness. He’d tremble; he’d quiver with all that intensity.” – Robert Motherwell

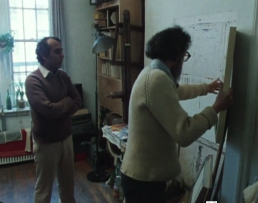

Artland’s Lost (and Found) Artist Series focuses on artists who were originally omitted from the mainstream art canon or largely invisible for most of their career. This edition’s featured artist is Harold Shapinsky (1925-2004), a contemporary of Mark Rothko and Robert Motherwell who began painting in the Abstract Expressionist style as early as 1940. Though most of the more famous Abstract Expressionists were aware of Shapinsky’s work, his intense, reclusive nature contributed to the fact that he was barely known by anyone and spent most of his life painting obsessively in his tiny New York City apartment. Then, an English professor from India, who also happened to be an art aficionado, saw Shapinsky’s work and changed the course of his life.

Shapinsky’s World

Harold Shapinsky was born in New York in 1925, the son of Russian Jewish immigrants. He took to art at a young age and studied at The Subject of the Artist, the school founded by Rothko and Motherwell. In 1950, at Motherwell’s request, Shapinsky’s work was included in a new talent exhibition at Kootz Gallery. Despite this promising beginning, Shapinsky did not flourish in the growing Abstract Expressionism market. Some have argued that it was Shapinsky’s personality, others that it was his similarity in style to De Kooning, that withheld Shapinsky from really being an acknowledged part of the scene. For decades, while artists like Rothko, Pollock, Motherwell and De Kooning enjoyed major recognition and fame, Shapinsky continued to paint in total obscurity in his tiny Manhattan apartment where he lived with his wife Kate.

Shapinsky’s Style

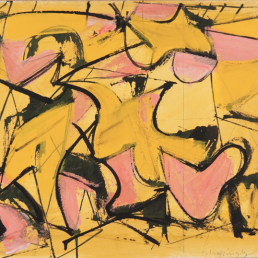

Shapinsky painted in the Abstract Expressionist style since the early 1940s until his death. With intense, thrusting brushstrokes and hard lines, Shapinsky fit in seamlessly with the style of other Abstract Expressionists at the time. People often commented on similarities between Shapinsky and De Kooning, and Shapinsky, well aware of this, therefore made a point out of never seeing De Kooning’s works. Yet if we examine De Kooning and Shapinsky more closely, it becomes clear that Shapinsky was a more pure abstractionist, and never ventured into figural motives like De Kooning would later explore. The determined, often sharp lines of his compositions which at times break up, at times connect the colours in his paintings are very much a world of their own and do not refer to the brushstrokes of De Kooning, or artists like Motherwell or Pollock, for that matter.

Moreover, his colour use was very different – he usually worked with primary colours. His Rainbow on Alabama Avenue (1948) is an excellent example of Shapinsky’s signature style – mainly working with reds, yellows and blues interspersed with white planes, Shapinsky creates a free-form yet structured impression of a rainbow. Untitled (1981) also works with primary colours, but here he moves into new territory, exploring different colour fields and how they interact in a softer style, without those hard lines and instead working with thicker, gentler brushstrokes. Untitled (1949) is a more psychologically intense piece where blues, purples and grays dance around each other in strange forms and compositions. In Untitled (c. 1970), there is an almost unmistakable hint of Mondrian and his journey towards abstraction – the lines remind one of his abstracted trees and piers.

Significantly, Shapinsky usually worked on modest-sized paper paintings, quite different from the large-scale canvases that soon became associated with Abstract Expressionism. This could offer another explanation why people didn’t understand his art or consider it to be on the same level as the art of other artists at the time.

"It could all easily never have happened. It was all built on the most precarious of coincidences. But, then again, it had to happen, because it was my karma to discover Harold Shapinsky, and it was Shapinsky's karma to be discovered by me." – Akumal Ramachander in the New York Times

“Shapinsky’s Karma”

In 1984, when the peak of Abstract Expressionism was already long gone and many of its great artists were no longer alive, Harold Shapinsky was to experience a surprising shift in fate. Akumal Ramachander, an English language professor and great art lover from Bangalore, India, saw slides of Shapinsky’s works for the first time and was stunned. Ramachander had met Shapinsky’s son David in Chicago, and when he told David that he had taken to promoting a young Polish artist, David asked Ramachander if he could show him slides of his father’s work. Seeing Shapinsky’s paintings, Ramachander was immediately deeply moved and told David that he should call his parents and tell them that he was going to promote his father’s paintings. He promised David that he would secure an exhibition for his father at a major gallery within a year, and that he would get the Encyclopedia Britannica to revise its entry on Abstract Expressionism to add the name of Harold Shapinsky.

“It could all easily never have happened,” Ramachander later told the New York Times. “It was all built on the most precarious of coincidences. But, then again, it had to happen, because it was my karma to discover Harold Shapinsky, and it was Shapinsky’s karma to be discovered by me.”

Setting the Ball in Motion

Ramachander started calling countless New York galleries, telling them he’d made a major discovery. He’d found an extraordinary Abstract Expressionist artist of the generation of De Kooning, Rothko, and Pollock who had been completely overlooked. The 32 galleries he approached were less than receptive, and he didn’t get a single appointment. But this did not deter him one bit. He paid a visit to the Shapinsky’s and they soon became friends. Then, he boarded a flight to Amsterdam where he met with the director of the Stedelijk Museum, who acknowledged that Ramachander had discovered a great artist. He referred him to a dealer in New York, but Ramachander, who had already tried his luck all over New York to no avail, decided instead to travel to London. There, he went to the Tate and refused to leave the reception desk until someone came to talk to him. Ronald Alley, the then keeper of the modern art collection, finally came down to meet this stubborn stranger. Once he laid eyes on the slides of Shapinsky’s works, he said: “You have made a major discovery.” He then told Ramachander that Shapinsky needed a first-class gallery, and referred him to James Mayor of the Mayor Gallery. Ramachander got in a cab and went straight over. Mayor was immediately convinced by the quality and importance of Shapinksy’s work and agreed to give him a retrospective exhibition.

Brought Into the Light

On May 21, 1985, Shapinsky’s 60th birthday, his retrospective at the Mayor Gallery opened to great acclaim. Of the 22 works that were shown, 19 were sold at prices ranging from $12,000 to $30,000. The exhibition was accompanied by a documentary about the artist on Channel 4 and an article in The Observer by none other than Salman Rushdie, who had become fascinated with the story of Shapinsky and Ramachander. An exhibition in Cologne followed, and Shapinsky started becoming more and more successful in the European scene.

Then, after the London retrospective, Lawrence Weschler of the New Yorker wrote a 16-page feature about the fairy-tale like circumstances surrounding Shapinsky’s discovery and his development in the art scene, entitled “Shapinsky’s Karma.” The piece helped to establish a buzz among the New York art crowd as well. Finally, Shapinsky also received exhibitions in the US. These included a special one-evening exhibition for selected guests at the Kennedy Center in Washington in 1985; a solo exhibition at Worth Avenue Gallery in New York in 1987; a solo exhibition at the Helander Gallery in Palm Beach; an inclusion in the touring exhibition “Abstract Expressionism, other dimensions”; and a retrospective of his work at the National Arts Club in New York in 1992. The National Gallery in Washington DC also acquired one of his works. Shapinsky and his wife continued to live a modest life in New York. His newfound success allowed him to keep painting in his signature style with fewer worries until his death in 2004. The record price for his work at auction is $78,000 for Untitled, sold at Christie’s New York in 2007. More recently, in 2010, Shapinsky’s works were on view at the Jerald Melberg Gallery. In the words of the gallery: “Shapinsky’s works communicate an energy and intensity that transcends their intimate scale.”