Articles and Features

Lost (and Found) Artist Series: Howardena Pindell

By Shira Wolfe

‘I asked my father, “What is this red circle?” He said, “That’s because we’re black and we cannot use the same utensils as the whites.”

Howardena Pindell

Artland’s Lost (and Found) Artist Series focuses on artists who were originally omitted from the mainstream art canon or largely invisible for most of their career. This edition focuses on the work of Howardena Pindell, an artist who has always exhibited widely, yet had to fight long and hard to find her place in the art world. In recent years, she has received more attention than ever.

Howardena Pindell’s Journey in Art

Howardena Pindell was born in 1943 in Philadelphia, and her artistic talent was recognised early on. Her third-grade teacher told her parents she was a budding artist and encouraged them to take her to museums and artist studios to help her artistic development. When she was eight years old, Pindell drove through Kentucky with her father and stopped at a root-beer stand. She noticed there that every cup had a red circle on its bottom. In an interview with Artnews, Pindell explains: ‘I asked my father, “What is this red circle?” He said, “That’s because we’re black and we cannot use the same utensils as the whites.”‘ This experience marked Pindell for life and made its way into her artistic practice. In a sense, her art has been about trying to change that circle in her mind.

During her B.F.A. at Boston University, she was trained as an academic painter with a focus on figuration. However, at Yale, where she received her M.F.A., abstraction was no longer stigmatised and she started to shift away from figuration. After graduation, Pindell moved to New York, where she discovered that it was in many ways far less ethnically integrated than had been the case in Philadelphia. Most of the arts institutions were sexist and racist, and Pindell struggled to get a job. After applying for 50 teaching positions and receiving 50 rejections, she finally landed a job in 1967 as a curatorial assistant at the Museum of Modern Art. She eventually became the associate curator in the Prints and Drawings department. Working at the MoMA as her day job, Pindell frequently had to navigate complicated waters. For example, there were certain meetings she could not attend because she was black. She would also experience difficulties with white female co-workers, angry at Pindell for not leaving work and picketing with them when she could not afford to lose her job because she did not have a husband to support her.

Meanwhile, Pindell continued to explore abstraction in her art. It took her about 20 years to arrive at full abstraction. In this area too, she constantly had to face difficult situations and a sense that she didn’t fit in. She was working primarily in an abstract manner while most black artists at the time were working figuratively in order to address political themes. And the abstract art world was, mainly, a white men’s playing field.

Materials and Style

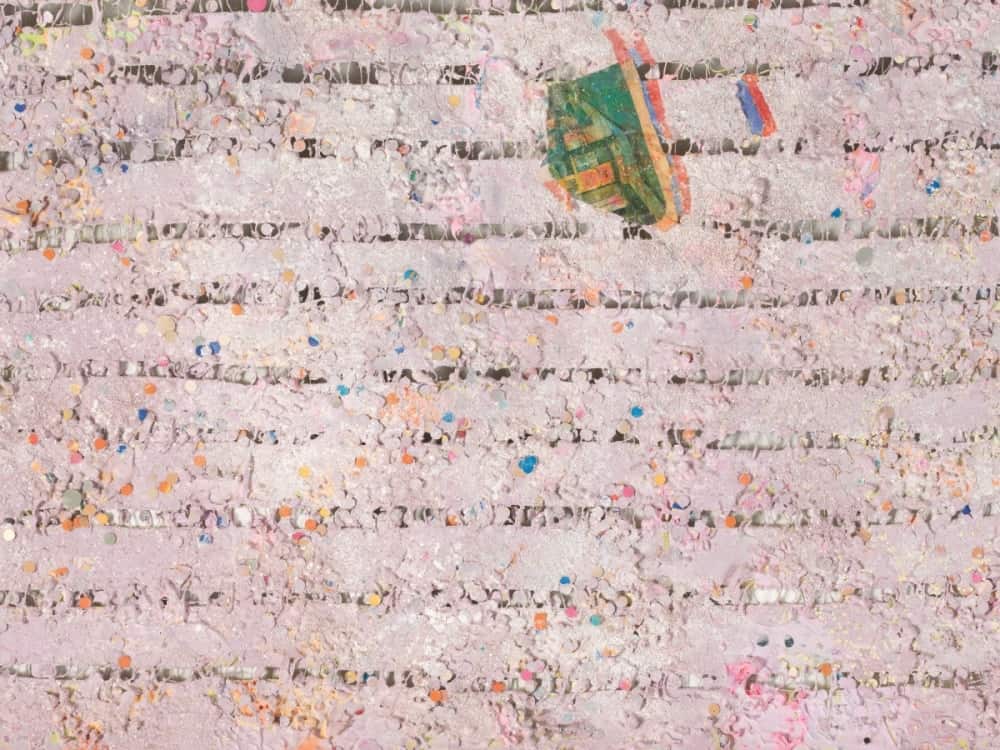

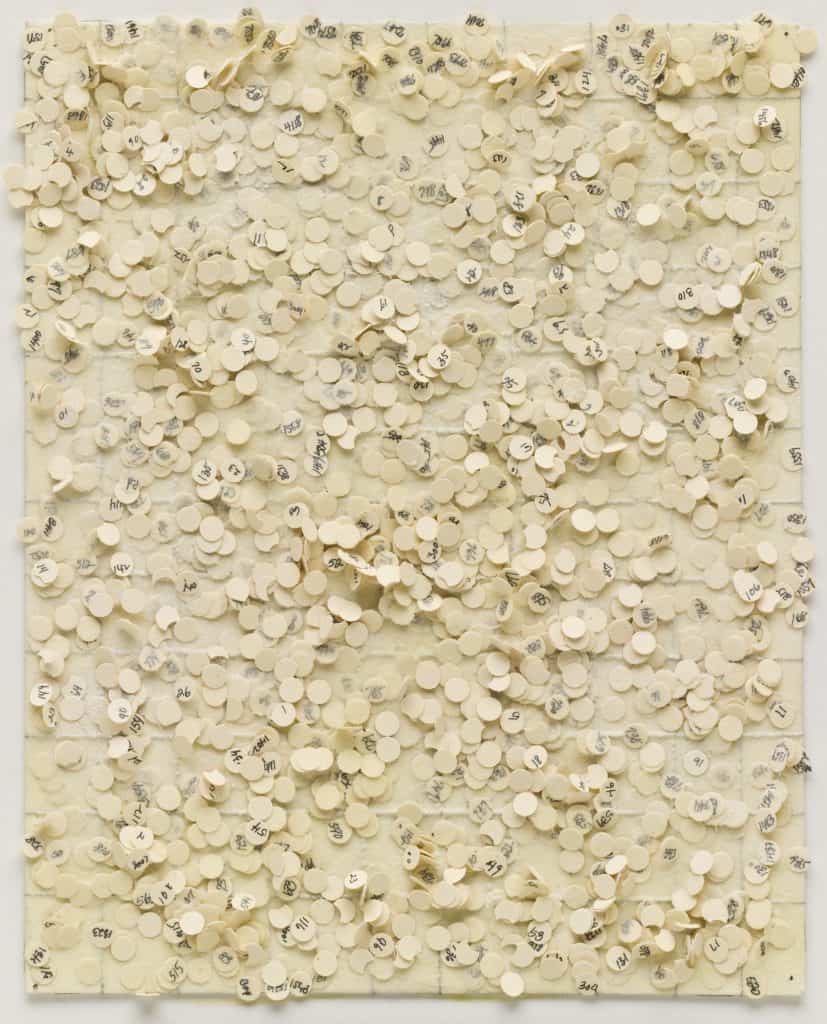

After discovering that she was allergic to oil paint, Pindell started using mostly acrylic and spray paint. Due to her low salary, she improvised with other materials for her art. She would take things from the trash at frame shops, and use leftover threads from sewing her own clothes to make grids of thread for her canvases. She also began to experiment with unconventional materials like glitter, talcum powder, perfume, and most notably, the little paper circles which are left over in hole punchers, sprinkling these over her paintings. For some of her first entirely abstract canvases, she layered Mylar-plastic templates which each had little holes punched into them on top of each other, then painted over them. These paintings took about three to four months to create, a process of constant layering and spreading, at random. Gradually, the hole punch approach began to play a larger role. She started to affix the tiny paper circles to her canvases by hand. Some were numbered, others sprayed with perfume. When she had finished an abstract canvas, it would usually be exhibited unstretched, unprimed, nailed to a wall.

“You never know when you’re going to wake up dead!”

Howardena Pindell

The Autobiography Series

Howardena Pindell’s Autobiography series, featured in a 2019 show at Garth Greenan Gallery in New York, reflects a particularly difficult yet extremely important and formative phase in Pindell’s life and career. The series was commenced following a car accident in 1979, which left Pindell with acute memory loss. That same year, Pindell also left her position at MoMA, deciding to distance herself from that part of the art world, and took up a teaching position at Stonybrook University. In an interview with Frieze, Pindell explains that she decided to make works that were autobiographical, and which at the same time addressed wider issues. In her words: “You never know when you’re going to wake up dead!”

The first piece in the Autobiography series, Autobiography: Oval Memory #1 (1980–1981) is a reflection of Pindell’s painstaking attempts to consolidate her memories after the accident. Pindell cut postcards and photographs, which she had collected for decades prior to the accident, into strips and layered them in collage work, alternating with acrylic paint. The layered fans of paint and paper, fragmented, ruptured, mirror Pindell’s own sense of fragmentation and healing process.

Wanting to speak out against racism, Pindell’s Autobiography: Fire (Suttee) (1986–1987) traces the silhouette of her own body on the canvas. This is a reference to the ancient Indian practice known as Suttee or ‘widow burning,’ in which widows are burnt alive on their husbands’ funeral pyres. She learned about this practice while travelling through India. Red, yellow, and orange handprints are overlayed on her body outline. The hands refer to the women who leave a handprint on the temple wall before the burning ritual, as well as to the immense historical significance of hands. For example, Columbus created a system in the Caribbean in the 15th century in which the hands of indigenous people were cut off if they did not regularly bring tributes of gold. And in the 9th century Belgian Congo, the hands of slaves were cut off if they refused to work on the rubber plantations.

Pindell’s works since her accident express her indignation about histories that have been too long untold, lost or covered up. She started working more with text because it was important for her that people would clearly understand what she wanted to transmit. One of her first text pieces, Autobiography: Air/CS560 (1988), referred to a poisonous gas used during the Vietnam War. Pindell continues to work with text, but divides her artistic practice into two strands: abstract works which are about beauty and finding peace, and more figurative works which directly address political issues.

Courtesy the artist and Garth Greenan

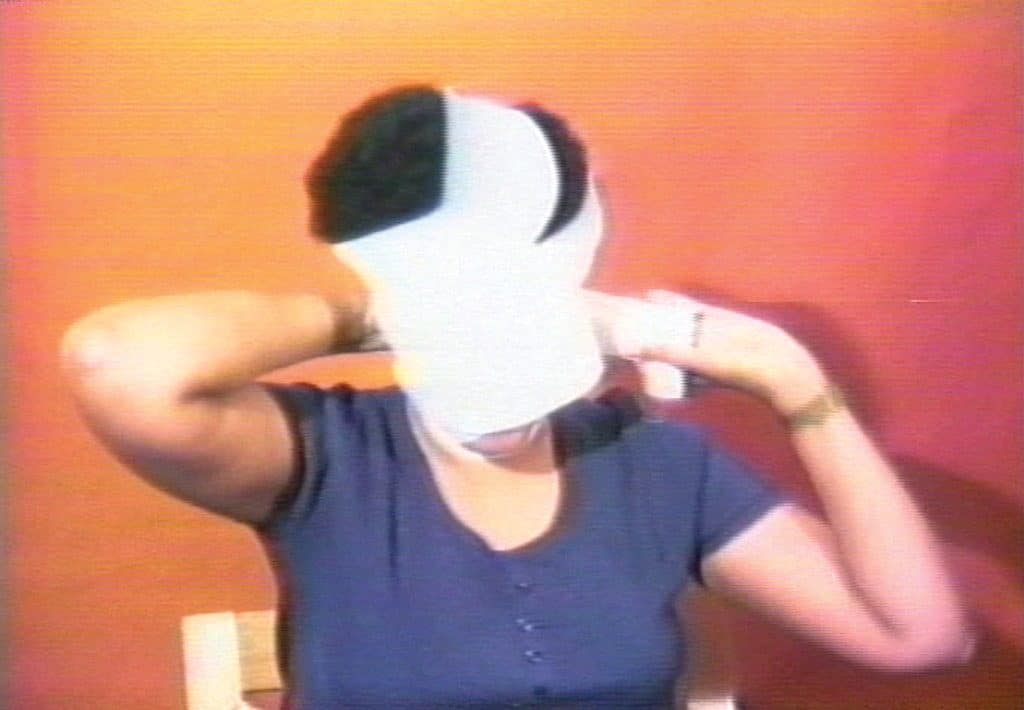

Free, White and 21

In 1980, Pindell made the short film Free, White and 21, which was a response to the women’s movement. There was an overriding attitude that the white women were in charge, and Pindell had at times been asked to back off since she’d brought up issues of race. In Free, White and 21, she plays two parts: a resistant white woman in sunglasses and a black woman, herself, engaged in a dialogue. The white character constantly questions the experiences that Pindell’s black female character shares, denying the reality of her experiences of oppression.

Shows and Recognition

Pindell showed at major institutions like MoMA PS1 in 1980, the New Museum in 1990 and LA’s Museum of Contemporary Art in 2007. But when Manhattan gallerist Garth Greenan visited her studio in 2012 and purchased all her paintings, the tide really turned for Pindell, who had often been so out of money she had to ration her food. Since then, Pindell has enjoyed a retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago in 2018, has been shown by Victoria Miro in 2019 and was a key part of Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963-1983, a show which has toured Tate Modern, Crystal Bridges Museum and the Brooklyn Museum, among others.

Relevant sources to learn more

Artnews

Garth Greenan Gallery

Victoria Miro

For previous editions of our Lost (and Found) Artist series, see: