Articles and Features

Lost (and Found) Artist Series:

Martín Ramírez

By Anthony Dexter Giannelli

Martín Ramírez became Martín Ramírez because he was lost in the United States and then he was found.

From the essay Martín Ramírez and Mexican Art by James Oles

An Outsider’s Winding Journey

Artland’s Lost (and Found) Artist series focuses on artists who were originally omitted from the mainstream art canon or largely invisible for most of their careers. This week we feature Mexican artist Martín Ramírez, who created a stunning visual world of meticulously cared for lines but has been often sensationalized as a mentally ill artistic genius, sometimes attributing – with the slightest bit of compassion – his eventual “mental breakdown” to his frailty, and culture shock.

The idea of the tortured soul, a neuro-divergent artist, using his “insanity” to tap into a level of creativity and expression so foreign and sublime to the mind of common society has proved to be a captivating narrative, simply irresistible to the masses. Audiences find a sort of cosmic justice when a misunderstood mind living a tortured life produces work of incredible beauty to be appreciated long after the artist’s lifetime. Would Van Gogh be perhaps one of the most celebrated artists of all time without the theatre, drama, and self-torture which resulted in the loss of his own ear, then sent to his unrequited love?

Shaping our understanding of Ramírez under the guise of his diagnoses given by a slew of anglophone mental health professionals who did not provide him with a single bit of Spanish speaking assistance throughout his 40-year stay (the same doctors who so lovingly referred to him as “mute”, “dull” or a “poorly nourished Mexican who speaks no English”) perhaps requires a bit more nuance in 2021. Perhaps given the available facts, critical hindsight, and a more holistic interpretation of Ramírez’s tortured soul portrayal, we shall end up with a picture of reality that has outgrown a cliched art-world narrative.

Road of Pitfalls

Martín Ramírez was born in Los Altos de Jalisco, Mexico in 1895, only 40 years after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo resulted in an area from Northern California to Southern New Mexico being ceded to the United States. Early-1900s along the Mexican-US border was an era under the lasting siege of an expansionist mindset that saw huge pushes for industrialization driven by infrastructure projects demanding an ever-growing number of labour and labourers. Eager to connect and develop these newly acquired lands, the U.S. to an extent “welcomed” an influx of foreign workers to make their dreams of an empire from sea to sea a reality. This drew a young, 30-year-old, Ramírez away from his culture and family, on screaming locomotives tunnelled through the cordilleras to the promises of prosperities in the north.

However, this prosperity was short-lived, and as the country soon took a nose-dive into the Great Depression, Ramírez was cast away and villanized alongside his compatriots by the new country they helped to build. Immigrant labourers were quickly run out of local communities, faced mass deportation, incarceration or – in the case of Ramírez – declared insane and taken into the custody of state mental institutions. After working on California railroads and mines and subsequently losing any source of income, Ramírez was in fact picked up by police on unclear grounds of being homeless and “mentally unstable”, and placed in the custody of the state.

His doctors relied heavily on his inability to communicate in English in their evaluations and justification for keeping him under the custody of the mental hospital. Instead, evaluations entertained speculations of syphilis, alcoholism, and drug abuse, finally landing upon “Dementia Praecox” an early term for schizophrenia. Since Ramírez could not properly articulate his sanity in a way that these doctors validated, their misguided and careless diagnosis remains the starting point for understanding and categorizing his work as an artist.

Based on the composition and construction of his works through found bits of crayon or graphite upon collaged bits of newspaper, magazine, and even exam table paper held together by a mixture of water and mashed potato, his “atelier” was not exactly out in the open. One can only imagine the lengths he had to go through to save his works from being purged by sanitary room sweeps and how many of his pieces did indeed get destroyed while he was under the alleged care of these institutions. During his time at the state-run hospitals his work was never fully encouraged or celebrated (at least openly) by the myriad of doctors or health care workers he dealt with on a daily basis, until Finnish artist-researcher on Art and Psychology, Tarmo Pasto came across his path.

Martín Ramírez & Expression through Confinement

Pasto would provide Ramírez with materials and collected his pieces to be featured in group exhibitions assembling works created in mental institutions. Among all the patients he exhibited, Ramírez was his favourite, even sending his work directly to the Guggenheim Museum’s director James Johnson Sweeney in New York in 1955. During regular private sessions, Pasto would try to dissect in conversation the meaning of his visual language, seeking a larger relation to the inner working of the psychotic condition. Though Pasto was infatuated with the captivating artistic expressivity of Ramírez and saved most of his surviving works from destruction by the hospital, the staff of DeWitt State Hospital was more interested in seeing him in the context of a debatably existing mental condition than as an individual.

The visual world of Ramírez consists of receptive and meticulously cared for lines that act to compose scenes of tunnels, locomotives, Caballeros, deer, and religious figures. Since Ramírez’s recent wider acceptance within the high art community, speculations of the influence and deeper meaning behind his characters and visual communication tend to reflect the audience’s or researcher’s viewpoint rather than Ramírez’s true reality. Those who want to connect his work to the tradition of post-war Mexican painters see an abundance of Nahua character representation, while those who wish to categorize him as an American artist love to pick up on his collage work and “commentary on pop or consumerist culture”. It’s hard to say without pure speculation what larger social commentary (if any) Ramírez was seeking to make in his work, though as a vilified, detained immigrant stripped of his freedom, the scene is ripe for finding meaning if that’s what you are searching for.

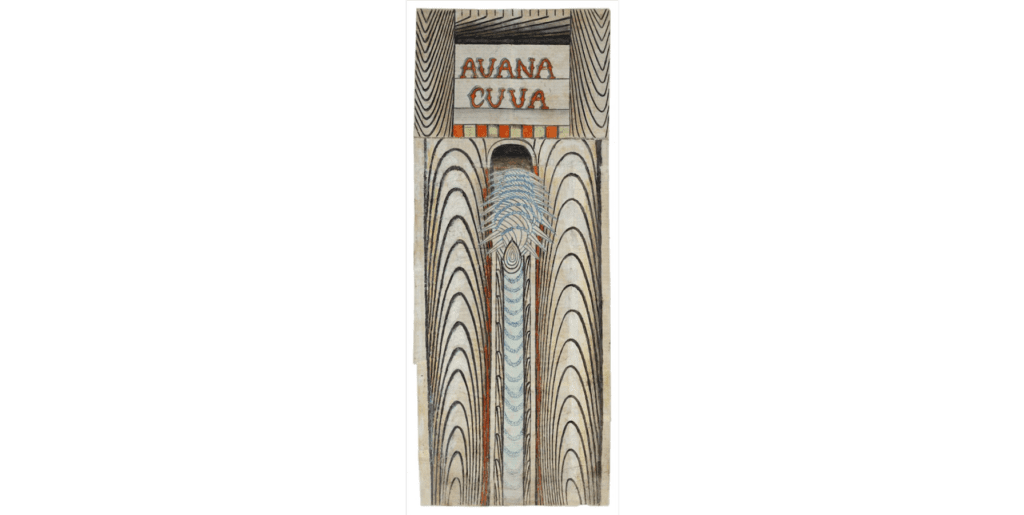

To completely play into the idolization of the purity of the outsider’s mind would rely on an artist receiving little to no outside influence; Ramírez was indeed isolated, yet he had access to newspapers highlighting important events such as growing Cold War tensions between Cuba and the United States as seen in his such works such as UNTITLED (Avana Cuua).

Furthermore, he was still subject to the slight nod of approvals to his works by the passing nurse, fellow patients, and finally in his relationship with Pasto. Much of the imagery can be factually traced to cultural influences of his life story, deer and other small creatures populated his family farm in Jalisco, which were the stomping grounds for the symbolic revolutionary horseback riders in a heavily Catholic influenced culture. Movement through the tunnels heading north dominated the middle era of his life leading to the upper reaches of the mines and tracks he laid down, ultimately ending in his final era dominated by confinement.

Ramírez’s use of two-dimensional perspective places the viewer on varying stages throughout his pieces: in some, the tunnels lead endlessly upon each other to no end as seen from a third-person perspective; in others the viewer is drawn into direct dialogue with masked creatures and icons, and in others yet the viewer is placed as a first-hand receiver of acts of judgment, confinement or danger.

While Ramírez is celebrated today, he lived through atrocities of racist immigration and xenophobic policies, and the struggles and individual stories of countless many who lived through the same have been lost to time. Due to Ramírez’s resilience, docile nature, and cooperation (as described by hospital staff) along with the happenchance discovery by a European immigrant researcher his story exists to this day and enjoys a celebrated existence within the art world. This celebration couldn’t save him from the abuse of a corrupt system that stacked him against his favour until his death at the age of 75, under the custody of the Dewitt State Hospital in Sacramento California. As recently as 2008, this celebration was still under contention between his living grandchildren and the benefactors who took advantage of works while for sale under his incarceration.

Relevant sources to learn more

More information and resources on Martín Ramírez including the involvement of his living heirs can be found compiled thanks to the American Folk Art Museum.

Often associated with Ramírez in the conversation of Outsider Art in the United States is Bill Traylor, read more about his unique story in Lost (and Found) Artist Series: Bill Traylor.