Articles & Features

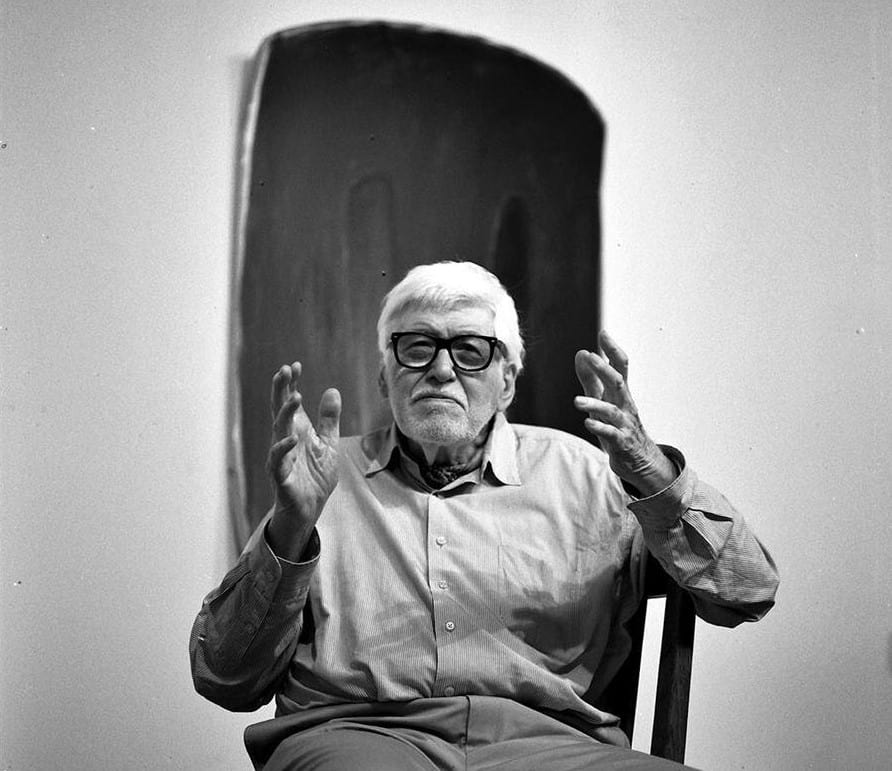

Lost (and Found) Artist Series: Ron Gorchov, The Artist Who Curved The Canvas In Every Direction

“To me the essence of sculpture is mass. In architecture, you feel volume. And painting stresses surface”.

Ron Gorchov

Artland’s Lost (and Found) Artist series focuses on artists who were originally omitted from the mainstream art canon or were largely invisible for most of their careers, in spite of innovations that mark them out as worthy of greater attention. However, this edition might be better titled ‘Lost (and Re-found)’ as this week’s subject, American painter Ron Gorchov, after a promising career in the 1960s and 1970s, stayed out of the public eye for more than twenty years to be finally rediscovered in the early 2000s.

Dead at the age of 90 on August 18th, he forged for himself an unorthodox path revolutionising painting in its very essence with the use of shaped, saddle-like canvas stretchers that conferred upon his paintings a three-dimensional quality, as unmistakable as it was innovative.

“My paintings are mostly made from reverie and luck”.

Ron Gorchov

Early life

Ron Gorchov’s artistic journey began when, only fourteen, he decided to take Saturday classes at the Art Institute of Chicago, the city where he was born in 1930. Later in life, he was to recall how a veteran – World War II was about to come to an end, and soldiers were returning home – had given him a paper bag full of art materials, his old brushes and half-squeezed paint tubes, saying they would be bringers of good luck.

After a year at the University of Mississippi, he returned to Chicago to attend the Roosevelt College and then the University of Illinois where he finished his studies in 1951.

Two years later, along with his wife Joy and their three-month-old son, Gorchov moved to New York in search of new opportunities; with only eighty dollars in their pocket.

Never abandoning painting – which he mostly did during the night time – he worked as a lifeguard and evening swimming instructor until, in 1960, he made a breakthrough and began showing his work.

On the art scene: 1960s and 1970s

The year 1960 marked a watershed for Gorchov. Tibor de Nagy Gallery gave him his first solo exhibition, a show that gained positive notes from critics, with Dore Ashton from The New York Times writing: “Unlike many painters of his generation, Mr. Gorchov handles colour with ease, and his canvases combine peacock blues, sea greens, carmine reds and pinks in sumptuous profusion”. That same year, the artist took part in the Whitney Museum exhibition Young America 1960: Thirty American Painters Under Thirty Six.

Swimming against the tide, Gorchov was presenting what he later defined “abstract surrealist” paintings in a time when the art world was taking the opposite direction, moving inexorably along the twin axes of Pop and Minimalism.

In this regard, the minimalist artist Carl Andre described the work as ‘retardétaire’, basically outdated. However, when years later Gorchov reminded Andre his comment, to his surprise, he replied that this was not exactly what he had said: “I said you were a ‘retarded terror’!”.

Anyway, the reception of Gorchov’s work was generally favourable, and those were the first of many shows that followed.

For some time, he had been thinking of abandoning the rectangle as a painting format in favour of less flat and sharp-edged shapes. He had considered various alternatives, for example placing a tennis ball behind the canvas to create a bulge, however without any satisfactory outcomes, and certainly none that felt like a solution to the problems that painting posed for him.

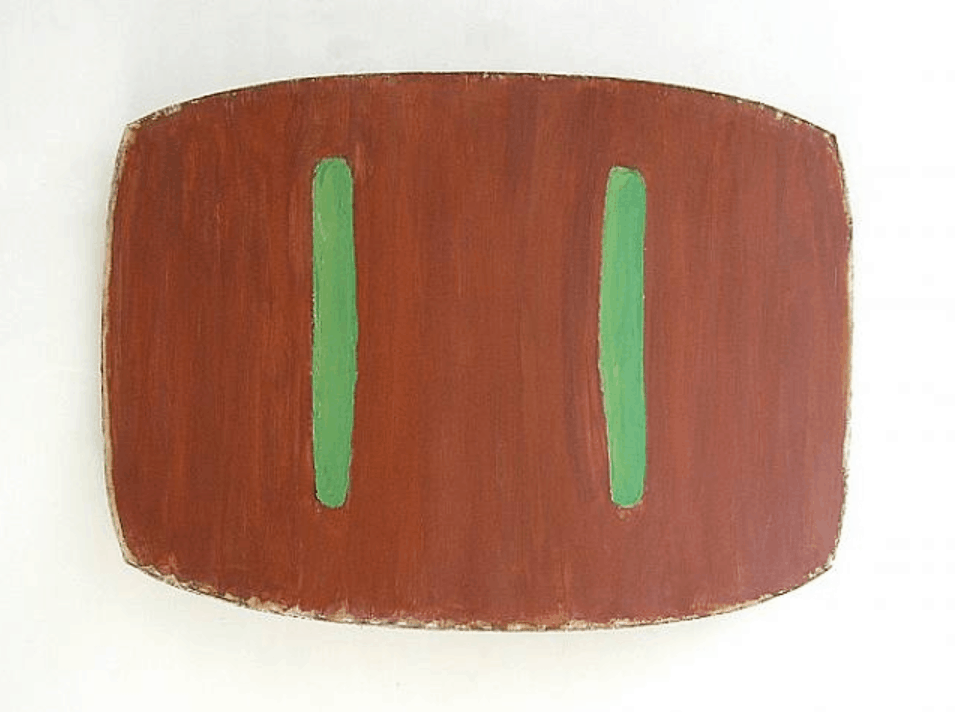

His breakthrough began with a conversation with the artist Al Held, who recounted a suggestion made to him to use shaped stretchers to accentuate the character of his coloured shapes. Even though both Gorchov and Held thought it was not a great idea, the latter was reminded of something he had seen at the Jewish Museum: a work by British artist and shaped-canvas pioneer, Richard Smith, involving a hyperbolic canvas extended with three-dimensional additions. In this case, he realised that even when cut out or built onto, a rectangular surface does not cease to be such. It was a light-bulb moment: he would give paintings an entirely different structure. Thus, Gorchov began experimenting with stretchers, and, by 1969, he had completed the first curved painting – “Mine” – a huge concave piece whose shape resulted in the corners being even more pointed than the ones of a typical rectangle.

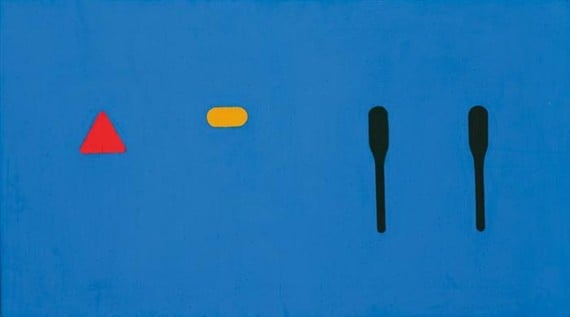

The artist progressively refined the stretcher’s shape starting from large-scale works such as Set (1971) and Entrance (1972) and ultimately finding in the shield-shaped support – at the same time concave and convex – his signature as well as the source of undiscovered creative possibilities.

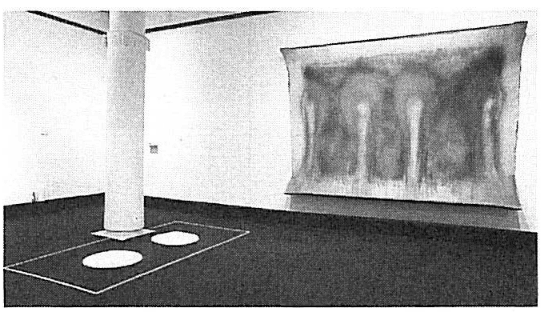

Interest in Gorchov’s work grew remarkably. In 1975, he had a solo show at the Fischbach Gallery and participated in two editions of the Whitney Biennial (1975 and 1977), as well as the now-legendary group exhibition Rooms that inaugurated PS1 Contemporary Art Center (now MoMA PS1).

Style and influences

Bending both inwards and outwards, Gorchov’s paintings disorient the viewer’s perception of dimension and depth. Not only that, they display their potential as discrete objects, almost becoming sculptures in their own right. Double motifs of varying biomorphic, organic shapes, sometimes almost mirroring each other, float on the often loosely painted monochromatic grounds — “symmetrical enough to be confusing” as the artist himself described them.

He adopted an ambidextrous way of painting, using his left hand for the left side of pieces and then switching to his right hand for the other. Bold, loose brushstrokes, applied in layers, leave exposed the irregular edge of the canvas – or linen – as well as the staples used to attach it to the stretcher, in a technique that art critic Roberta Smith called ‘clumsy’, in the most endearing sense of the term; while the artist liked to define it ‘elementary’ by reason of its absolute simplicity.

Initially influenced by John Graham’s paintings of the late 1940s, during the 1970s Gorchov belonged to a group of maverick New York artists (including Richard Tuttle, Blinky Palermo, Frank Stella, and Ellsworth Kelly) who believed painting had not run its course yet and needed to be pushed to further limits – just when the rest of the art world was going beyond Modernist painting and sculpture.

Already in the 1960s, Gorchov had identified six key issues to address; those included “freely painted edges,” the “desire to continue painting on stretched canvas”, “perception of canvas as both object and void”, and also the “synthesis of painting, sculpture, and architecture”. He “opposed the ad-hoc acceptance of the rectangle, wanting a more intentional form that would create a new kind of visual space”, and his research led him to the gently curved surface that became instantly recognisable as his.

Challenging both the strong subjectivity of Abstract Expressionism and the cold objectivity of Minimalism, he was able to create a delicate balance between form and emotional content. Even though his pieces’ evocative titles offer hints of content referring to mythological and biblical stories, the artist used to paint rather intuitively, without a particular subject in mind, ascribing a significance only in retrospect. He once explained: “When I do a painting and I look at it, I have to ask myself, how did I feel when I did that? Because I was involved with making it, I don’t know how I felt. So then I study the painting to figure it out…and I try to find a story that feels like how I felt”.

“I don’t want to be the kind of artist that feels he has to make perfect work. Work doesn’t need to be perfect. I like the illusion of perfection”.

Ron Gorchov

Rediscovering Ron Gorchov: the early 2000s

Other than a handful of exhibitions (at Susanne Hilberry Gallery in 1985 and 1994 and Jack Tilton Gallery in 1990 and 1992), the 1980s and 1990s turned out to be rather quiet decades for Gorchov’s career. “Nothing worked well for me in the ’80s. The ’90s passed quickly”, he stated.

Regardless of whether it was by choice or by other circumstance, the artist never stopped painting but stayed out of the public eye until 2005, when Vito Schnabel curated a small survey of his paintings at his eponymous gallery. It was his first solo show in over a decade. On that occasion, Robert Storr – Gorchov’s long-time advocate – wrote: “If he gets the breaks and goes the distance this time, he will be one of the greatest comeback kids the New York School has ever seen. What are the odds of this happening?”. And, indeed, he seized the opportunity and returned to prominence.

In 2006, a solo exhibition at MoMA PS1, Ron Gorchov: Double Trouble, presented his recent body of work for the first time; since then, a string of solo and group shows have followed, both in the US and overseas. Among others, his life’s work has been featured by numerous international galleries, including Centro Atlántico de Arte Moderno, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria; Cheim & Read, New York; Thomas Brambilla, Bergamo; Sotheby’s S|2, London; Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin; Maruani Mercier, Brussels; Modern Art, London; and Larsen Warner in Stockholm, is currently hosting Ron Gorchov: Recent Work (September 3-October 3) as a tribute to his artistic life and work.

Throughout his career, he always believed that artists should create for the century to come, not the one they live in, and, in fact, he was able to do so. Interviewed by Robert Storr and Phong Bui, Gorchov said: “I don’t know if many artists thought about picking their time, but I’d like it to be now”.

In spite of the critiques that saw his work as repetitive, Gorchov, throughout his six-decade-long career, proved to be consistent with his artistic vision, developing a unique artistic vocabulary that cannot be classified into any single artistic movement or moment; he showed commitment and faith in painting at a time when the medium was deeply underestimated. “Even though it was always made for a small audience, I believe that painting will be looked at; it’s lasted 40,000 years, why not another 40,000 years? Ok, let’s say it’ll only last another 10,000 years, why should it come to a dead stop?”.

Relevant sources to learn more

For previous editions of the Lost (and Found) Artist Series, see:

Lost (and Found) Artist Series: Vivian Maier, Street Photographer

Lost (and Found) Artist Series: The Visual Poetry of Maria Lai

Lost (and Found) Artist Series: Saloua Raouda Choucair