Articles and Features

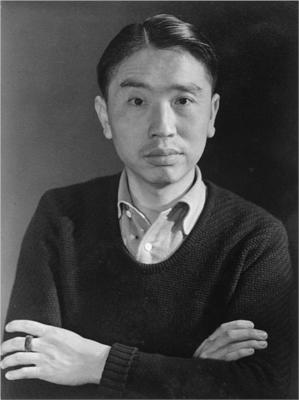

Lost (and Found) Artist Series: Sanyu

By Shira Wolfe

‘I must not leave Paris, in order to live a bohemian life.’

Sanyu

Artland’s Lost (and Found) Artist Series focuses on artists who were originally omitted from the mainstream art canon or largely invisible for most of their career. This week, we follow the life and art of Sanyu, a Chinese artist who moved to Paris in the ‘20s and is often compared to Henri Matisse. Though he was the most well known Chinese artist in Europe during the ‘30s, the artist died in relative obscurity and poverty in 1966. Today, his works are a steady presence on the secondary market and are selling for over $20 million at auction.

Sanyu in Paris

Sanyu was born on October 14, 1895 in Nanchong, China, the youngest child of a wealthy silk factory owner, where he was tutored in calligraphy and painting from a young age. He moved to Paris in 1921 and rented an apartment in Montparnasse where he soon became a fixture of its bohemian café culture. He studied art at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts and the Académie de la Grande Chaumière and here, he first came across the custom of painting nudes. In Paris, he also discovered Picasso and Matisse.

During the ‘20s and ‘30s, the artist produced over 2000 drawings and watercolours and also began experimenting with oil paintings, prints, mirror paintings, and sculptures. What set him apart from his fellow Chinese artists in Paris was the fact that while they were studying anatomy and Western techniques by the books, Sanyu was searching for a signature style. His work combined the history of European still life and figurative painting with the traditions of Chinese calligraphy.

Exhibitions and Support

By 1929, Sanyu received the support of art dealer Henri-Pierre Roché, who had supported the likes of Duchamp, Braque and Brancusi before him. However, their relationship eventually soured due to arguments over money – Sanyu was heavily reliant on him for income.

Sanyu was the first Chinese artist to be presented at the Salon des Tuileries in 1930 and the Salon des Indépendants in 1931. Between 1931 and 1934, he had five solo exhibitions in Paris and the Netherlands, which were positively received. His exhibitions in the Netherlands were organised by his patron Johan Franco, a composer and relative of Vincent van Gogh’s, who had strong ties to the art world. It was thanks to the support of Franco, and his wealthy brother, that Sanyu was able to survive and continue living his bohemian Paris life. When his brother died, he lost his only stable source of income. At times, he wasn’t even able to afford basic art materials.

While most of his fellow Chinese artists returned to China after finishing their studies in Paris, Sanyu was determined to stay and be part of the Modernist movement. Yet his sceptical approach to the art market, his nonchalance and singular character hindered his potential for commercial success in the 1930s. Although Sanyu continued to have exhibitions at the Salon des Indépendants throughout the ‘40s and ‘50s, he fell into oblivion after his death. Widespread recognition would only come to him posthumously.

‘Sanyu was a radical artist, who fused the traditions of East and West like no one else really before him.’

Eric Chang

Sanyu’s Nudes

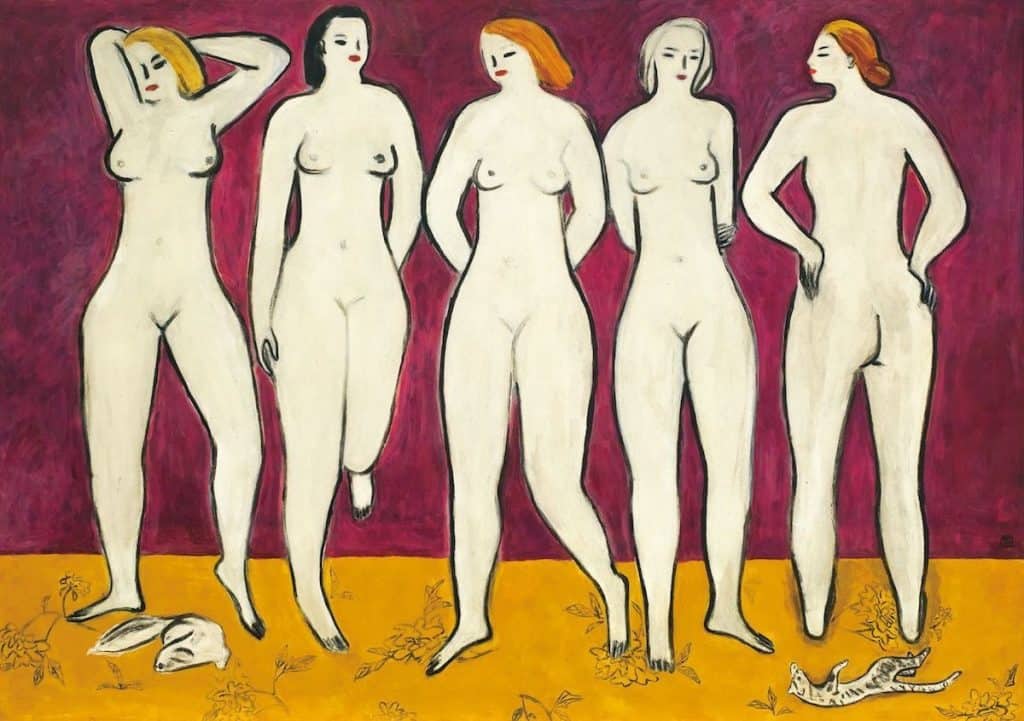

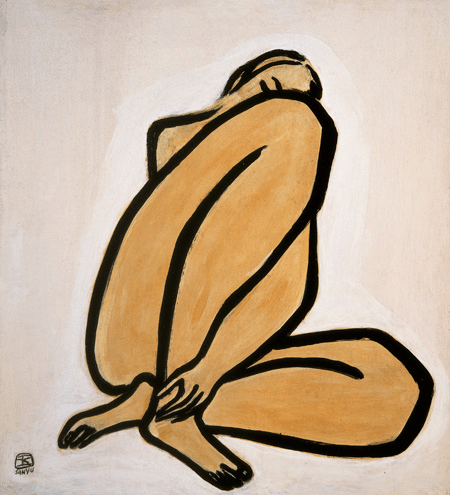

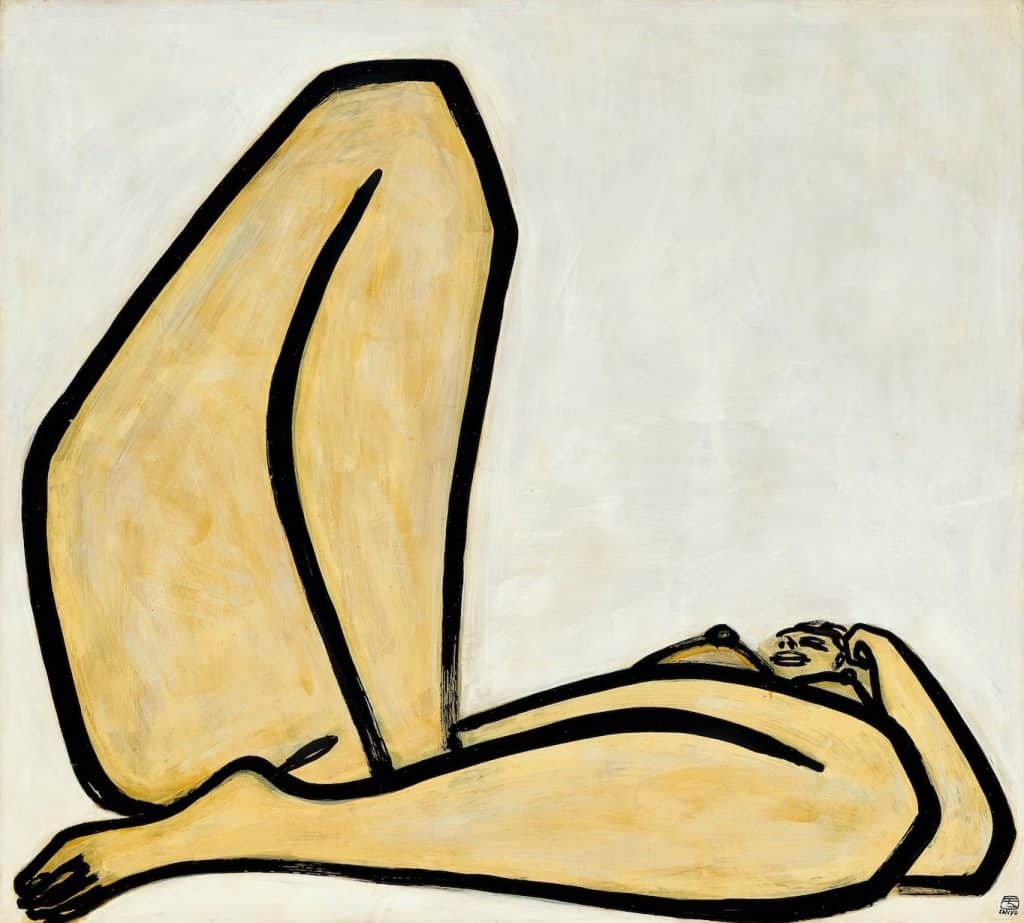

Sanyu is known especially for his characteristic nudes – with expressive, smooth lines, he would outline the contours of the nude body, filling the canvas almost completely with their monumental limbs. Combining ink drawing and watercolours, he often made thick ink outlines, accentuating the voluptuous, sensual nudes with statuesque thighs and long legs.

Eric Chang, Deputy Chairman of Asian 20th Century & Contemporary Art at Christie’s Hong Kong described Sanyu as “a radical artist, who fused the traditions of East and West like no one else really before him.” After all, in Sanyu’s native China, there had been no tradition whatsoever of depicting nudes. And yet, he always retained a strong connection to his Chinese roots – calligraphy, lyricism, and Chinese motifs fused seamlessly with a more modernist French approach to artistic expression. His expressive lines created with ink and brushstrokes created the best kind of simplicity – just the powerful contrast of a nude female form filling almost the entire expanse of a canvas, outlined in black against a bare background.

Still Lives, Animals and Landscapes

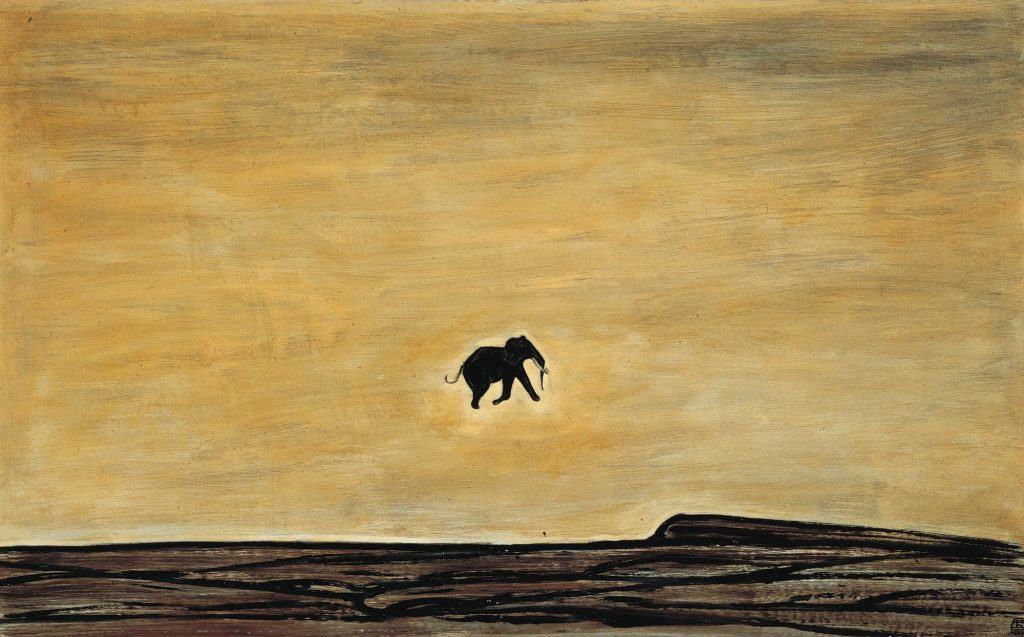

Sanyu’s still lives made up a major part of his oeuvre. He formulated his own nostalgic idea and portrayal of his native China. He chose to portray flowers that recalled the tradition of Chinese painting – lotuses, chrysanthemums, peonies, plums and bamboos were all favourites. Animals, too, often appear in his’s paintings. The early works often portray pets like cats and dogs, shown in a domestic setting. His later animal works and landscapes from the 1950s and 1960s are darker, reflecting topics like loneliness, solitude, and the unknown. Here, he placed exotic animals like elephants, giraffes, or leopards on their own in vast landscapes, eliciting existential questions of loss, homelessness and a search for one’s own place.

New York and Ping-Tennis

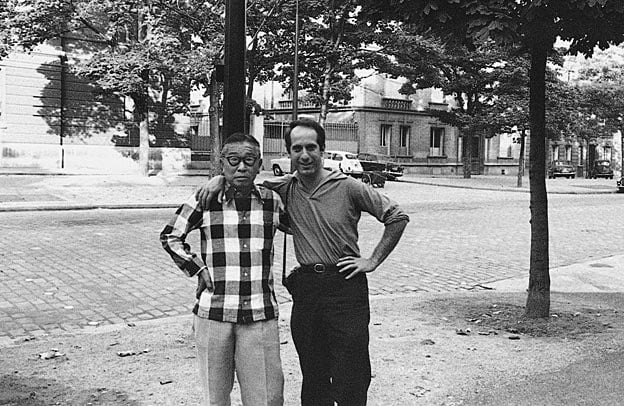

Like many artists before him, Sanyu also explored the New York scene. It was to be a short trip. ‘Sanyu came to America to promote ping-tennis,’ recalls Robert Frank, the American photographer known for his seminal photography collection The Americans. Frank and Sanyu became close friends and roommates in New York.

In desperate need of money, the artist had invented a new game called ‘ping-tennis,’ a mixture between ping-pong and tennis. In 1948, he came to America, hoping to promote this game and make good money. He even told Frank at one point that he was done with painting, believing that ping-tennis was the only solution for him to attain financial success. Suffice to say, ping-tennis did not catch on. Trying to help, Frank organised an exhibition for Sanyu, but none of his paintings sold. Disillusioned, Sanyu decided to return to Paris and left all his paintings to Frank as a way to repay him for supporting him during his time in New York. By 1950 he was back in Paris. He would continue to promote and teach ping-tennis for the rest of his life, and Frank and Sanyu maintained a life-long friendship.

Rediscovery

Sanyu died in his studio in 1966, the result of an unintentional gas leak that killed him in his sleep. It took until 1988 for him to be rediscovered. Following an exhibition at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum, Taiwanese dealers recognised his importance and exhibitions at the Musée Guimet and the Musée Cernuschi’s followed. Today, his works sell for incredible amounts at auction. His Nu (1965) sold for $25,253,527 at Sotheby’s Hong Kong’s Modern and Contemporary Art Evening Auction, and just this month, Five Nudes (1950s) sold for $39.1 million dollars at the 20th Century & Contemporary Art Evening Sale in Hong Kong, setting a new record for the artist. After 50 years, Sanyu is finally getting the attention (and his work the economic rewards) he sought but which eluded him during his lifetime.

Relevant related sources

For previous editions of our Lost (and Found) Artist series, see:

Tehching Hsieh

Sonia Gomes

Maria Lai