Articles and Features

Lost Art. A History Of Unfortunate Accidents

By Pablo Anton

Throughout the centuries art works have been exposed to random misadventures, cataclysms and various Acts of God that have ended their existence. Here we cast an eye over a number of these more notable occurrences, some documented rigorously, and others more anecdotal, but all recounting some of the many mischiefs that have cost us treasured pieces of our shared material culture.

An ancient wonder shaken by nature

One of the most iconic losses to the calamities of time is perhaps The Colossus of Rhodes. This Ancient Greek statue built in 280 BC by greek sculptor Charles of Lindos is one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Built to celebrate the victory of Greece over the Cyprian rule of Rhodes, the statue was at that time the tallest ever raised (it was approximately as big as New York’s Statue of Liberty), straddling the harbour. The statue had been dedicated to Helios, god and personification of the sun, as Rhodes was one of the few Aegean Islands in the archipelago which venerated this particular deity.

Completely destroyed by an earthquake in the year 226 BC, the statue was never rebuilt. The Colossus of Rhodes might have been lost over 2000 years ago but it has continued to cast its rather large shadow over the creative imagination, as if this loss had been impregnated in collective memory. It has served as a source of inspiration for many artists over the years: painters like Goya and Dalí, poets like Sylvia Plath or film directors like Sergio Leone have paid their tribute to the ancient wonder. There is a powerful and magnetic feeling in the loss of something so big and deific.

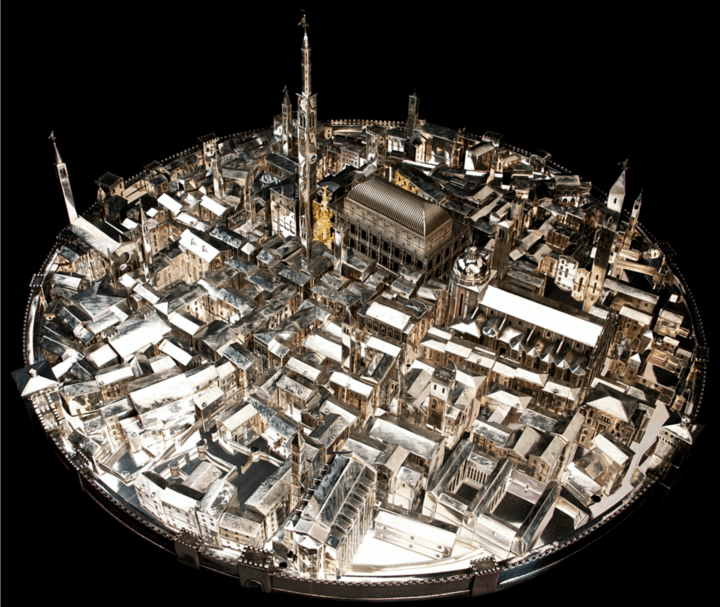

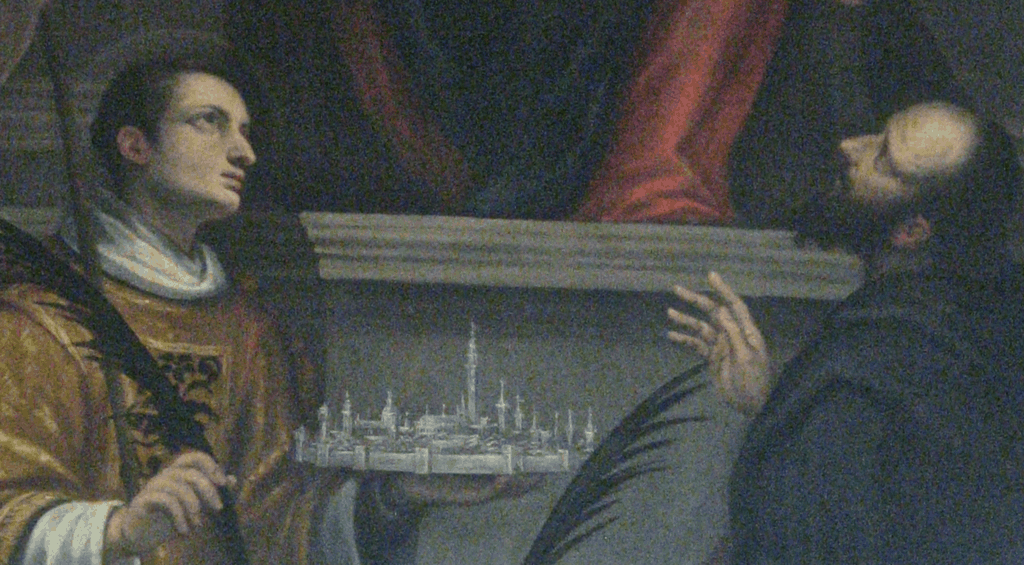

Not everything that shines is silver

The Jewel of Vicenza was produced by Italian architect Andrea Palladio in the 16th century. It consisted of a detailed miniature replica of the city of Vicenza, in the north of Italy, carved in great detail from wood, but covered in a thin sheet of silver. This wooden piece of lost art was first created as an offering to the Virgin of Mount Berico in the hopes of avoiding further contagion of a plague that had seen the population of the city vastly depleted. It inspired many Italian artists such as Alessandro Maganza or Francesco Maffei, who featured the sculpture in their artistic creations.

Its demise occurred some centuries later when Napoleonic troops purloined the piece from Italy during the Italian Campaign in the French Revolutionary Wars in 1797. Their initial intention was to obtain silver from the model. Little did they know that the piece wasn’t made entirely of silver and that instead of melting a large volume of precious metal, they were burning a mostly wooden model.

Casting pearls to the swine

The theft of the Nativity with St. Francis and St. Lawrence by Caravaggio is among the most bizarre stories of lost art, with an extraordinary fate befalling the great early Baroque masterpiece.

Painted in 1600, the piece portrays the nativity of Jesus and was kept in the Oratory of Saint Lawrence in Palermo. Because the investigation of this theft was never properly resolved, there are still many different theories to explain how this painting could disappear so completely with seemingly no prospect of recovery. Probably one of the most absurd yet compelling hypotheses is that this art work was stolen by the Sicilian Mafia in 1969. Intending to ransom the priceless work, a deal never materialised leading the mobsters to cut the work into tiny pieces after which they fed it to pigs in order to eradicate all trace evidence of its existence.

The Thames swells its banks

War and Peace is an engraving on Indian laid paper by mid-19th-century British artist Sir Edwin Landseer, a favoured artist of Queen Victoria’s court. The art work, which was stored by the Tate Gallery in London, saw its ruinous end when the museum basement was devastated by a natural disaster: the flooding of the famous Thames river in 1928. This lost art piece, amongst many others, which showed the opposition of the chaos and ruination of war to the tranquility of peace, was submerged by the waters as they filled the museum’s vaults.

The Schloss Immendorf Castle Fire

Many stories of lost art can be traced to the destructive power of fire. Among the most noteworthy is the case of the exquisite wall paintings made by Austrian symbolist painter Gustav Klimt for the Great Hall of the University of Vienna in the 20th century.

The set of three paintings represented the main disciplines of the University: Medicine, Philosophy and Jurisprudence. They were never exhibited at the Great Hall of the University as the outrage of Austria’s traditional and purist society believed the art was indecent and “pornographic”. Therefore, after this initial rejection, Klimt refused to arrange any further public exhibitions of his art and was involved in the foundation of the Vienna Secession movement. This group of artists aimed to fight convention in the Austrian art scene, as well as fostering a community amidst the other painters who felt subjugated by the dictates of the Austrian art academy.

Haunted by its “obscenity” origins, the set of three paintings was later on moved along with other art works to Schloss Immendorf, a castle in the district of Hollabrunn in the northeast region of Lower Austria. The paintings enjoyed a brief public showing before the castle was burned (with the art works in it) by Nazi troops in an attempt to prevent enemy hands from controlling the Austrian building.

MoMA burns

Another big art loss to the destruction of fire was the Water Lilies panel exhibited at MoMA in New York, painted by impressionist Claude Monet between 1914-1926. This fatal casualty took place in 1958 when MoMA caught fire due to the negligence of repairmen who were working on the air conditioning of the second floor of the building. While enjoying a smoking break, a piece of clothing caught fire which eventually ignited some open paint cans nearby. Soon enough, abundant smoke came filled the premises and people got trapped on the upstairs floors.

Finally, even though MoMA staff tried their valiant best to rescue the most iconic pieces by transporting them hand by hand down the stairway and out of the building, the firefighters who were trying to save the building accidentally destroyed a few art works in the process, part of Claude Monet’s panel included.

Swissair Flight 111

Lost art can also be caught up in the middle of enormous human tragedies. This is the case of a Picasso painting titled “Le peintre” (The painter) worth $1.5 million. This piece, aboard Swissair flight 111 traversing the New York – Geneva route, was part of the aircraft’s commercial cargo when the airplane crashed near Nova Scotia, Canada in 1998. After an exhaustive investigation, it is still unknown how the accident occurred and the technical reasons why the aircraft crashed.

A matter of politics

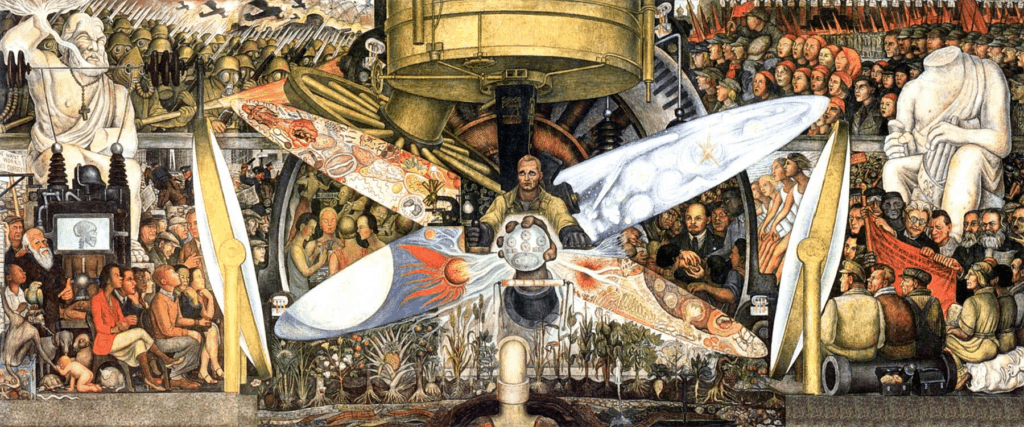

They say that good art should always reflect the times in which it was made, and Mexican painter Diego Rivera added many critiques to capitalism in his art. Moving to the US with his wife, surrealist painter Frida Kahlo, Rivera was commissioned to decorate the walls of the newly minted Rockefeller Center’s Lobby in New York.

His idea was to scrutinize the evolution of humankind and societies through three different panels: a first one portraying a worker manipulating machinery as a reference to industrialization, a second one to the left “the Frontier of Material Development” depicting the struggles of production through capitalism and a third panel to the right “ the Frontier of Ethical Evolution” depicting a communal world where people joined forces for a shared good – in effect a visual embodiment of socialism, which to US eyes and ears was ostensibly communism.

Rockefeller and Rivera kept having disagreements over the content of this now lost art work, especially as it also featured Lenin, a terminal provocation for Rockefeller the capitalist titan. Finally, the owners decided to fire Diego Rivera and repaint the wall with another commission altogether from a different artist.

The Artist’s self-critique

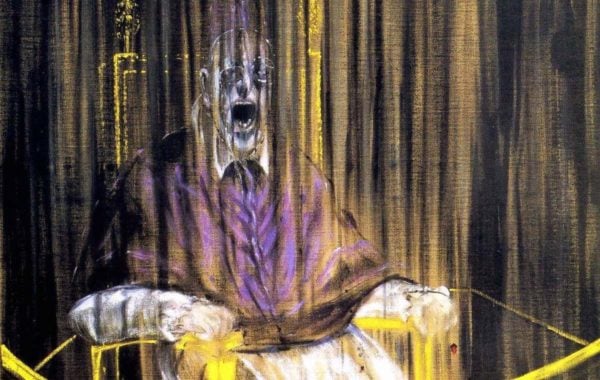

Lost art can also be destroyed by its creators, as disappointment and frustration are also often inevitably part of the creative process. In this example, figurative painter Francis Bacon created a series of 50 reinterpretations of Velázquez’s “Pope Innocent X” painting. It is well-known that Bacon had a tendency to destroy the art he wasn’t satisfied with. Many of the paintings in this series were in fact destroyed by the artist’s hand.

Bacon’s interpretation depicted a bleak caged reimagining of the pope portrait, which to many experts meant the death of God and the human extinction of all His representations on Earth. To others, it meant the killing of a father figure. Francis Bacon himself didn’t go as deep into the psychoanalysis of his work and stated that he was simply following Velázquez’s lead and that as the 17th-century Spanish painter once had tried to refresh another artist’s work like Titian’s, he was also doing likewise.

The Sitter’s prerogative

Art can be destroyed by creators, as it can also be destroyed by those who commission and thus ultimately own it. This is the case with Winston Churchill’s portrait from 1954 commissioned from artist Graham Sutherland. Funded by the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the art work was meant to be the ex prime-minister’s 80th birthday gift.

Churchill who saw the painting 10 days before the art work would be presented to the public in a ceremony at Westminster Hall, said that it made him “look like a down-and-out drunk who has been picked out of the gutter in the Strand”. Churchill demanded the portrait not to be shown at the ceremony but was persuaded by the artist, who claimed donors would be offended if the piece wasn’t shown to the public.

This portrait was intended to be hung in the Houses of Parliament, but since it was a present to Churchill, he decided instead to hide it away from public scrutiny at his country house in South East England. Churchill was embittered by his likeness and hated the portrait, to such extent that his wife destroyed it in what we believe was a clear attempt to soothe Churchill’s ego.

.

Relevant sources to learn more

Read more about the topic on MoMa

Read more about the topic on Tate

Gustav Klimt profile on Artland

Five Famous Painting Politicians

Stories of Iconic Artworks: Diego Rivera’s Rockefeller Mural