Articles and Features

Noah Davis at

David Zwirner, New York

Christian Viveros-Fauné | Kulchur Vulture

Viveros-Fauné is Artland’s inaugural Chief Critic and the contributor of this regular column. Based in New York City, he writes primarily about exhibitions and the cultural landscape there. His articles also feature Artland’s revolutionary 3D exhibition tours that enable the viewer to pay compelling virtual visits to actual exhibition spaces in support of the texts.

The first time I saw Noah Davis’ paintings and curatorial work I was so astonished I leaned on the poet John Ashbery to explain: “From the moment that life cannot be one continual orgasm, surprise is promoted to the first rank of emotions.”

Shoehorned into a tiny basement apartment on Avenue C were two canvases by painter Henry Taylor, a photograph by Lyle Ashton Harris, a mysterious video by Davis’ wife, Karon Davis, and four paintings, twenty collages and one found sculpture that constituted Noah Davis’ first New York outing as an artist and curator. The words I wrote in 2015 for the Village Voice apply equally today to David Zwirner’s mesmerizing display of the gifts of the late L.A. wunderkind. Five years after his passing at age 32 from a rare form of soft tissue cancer, Davis’ canvases continue to suggest “unacknowledged possibilities for American painting”; the electricity they engender still feels “like being blasted off on a champagne cork.”

Praise for Noah Davis should be uttered with hands raised, encomiums should be written in sharpie. What he did in a few short years places him among the first rank of American artists and arts organizers. On the evidence of the current exhibition, sensitively organized by Helen Molesworth—the ex-LA MOCA chief curator was a close collaborator of the artist in life and remains a principal keeper of his flame—Davis’ brief career shone brightly if enigmatically, like his dreamy painting of the Hollywood sign missing its last two letters, which he cannily titled NO-OD for Me (2008). Davis’ achievements include, by Molesworth’s count, an oeuvre consisting of more than 400 paintings, collages and sculptures, but also a powerful Gesumtkunstwerk: The Underground Museum, set down like a lantern in Arlington Heights, an underserved African-American and Latino neighborhood in L.A.

“African-American characters share space with ghostly figures and landscapes that either emerge or disappear into bone dry applications of paint.”

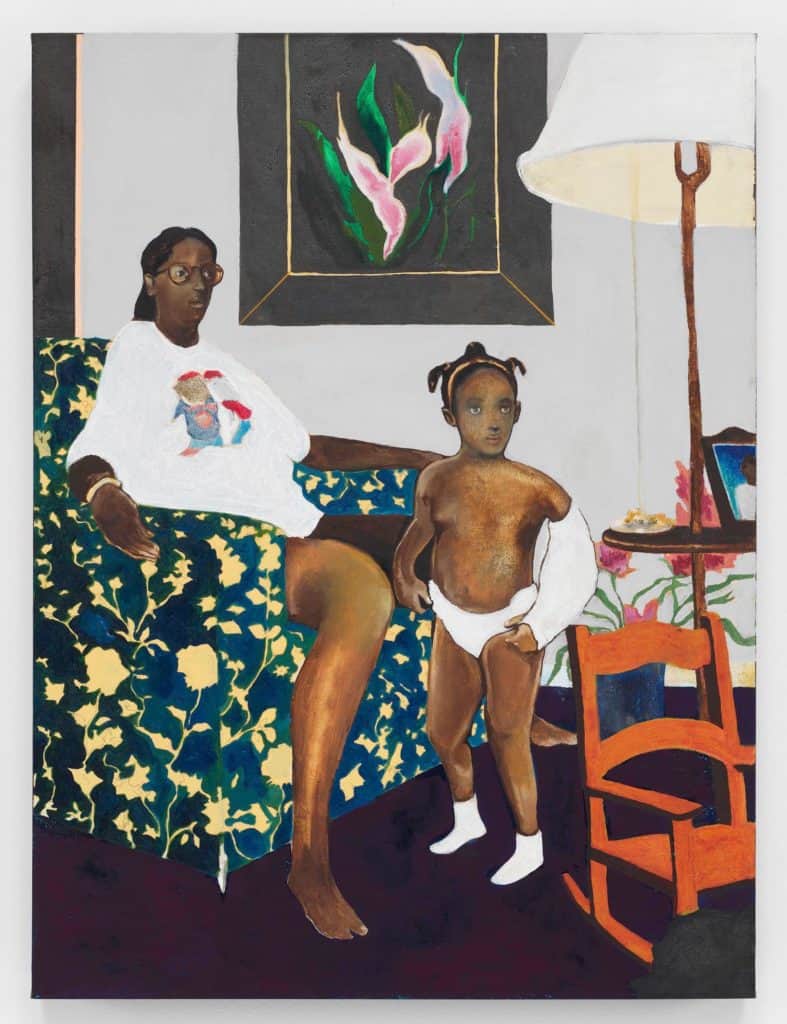

Both paintings and total work of art are well represented in David Zwirner’s eponymously titled exhibition, which covers the block-long length of the gallery’s two 19th Street locations. First up are 27 examples of Davis’ moody figurative canvases, which traffic in a lush, palimpsest-like realism, where mostly African-American characters share space with ghostly figures and landscapes that either emerge or disappear into bone dry applications of paint. The canvases’ putative subject matter—surrealist narratives framed by spatial dissonances done in alternately doleful and exuberant colors—as well as their pared down elegiac style simultaneously invoke Neo Rauch and Kerry James Marshall, among other influences, while offering concentrated doses of a youthful artist’s mongrel vision: what he called “instances in which black aesthetics and modern aesthetics collide.”

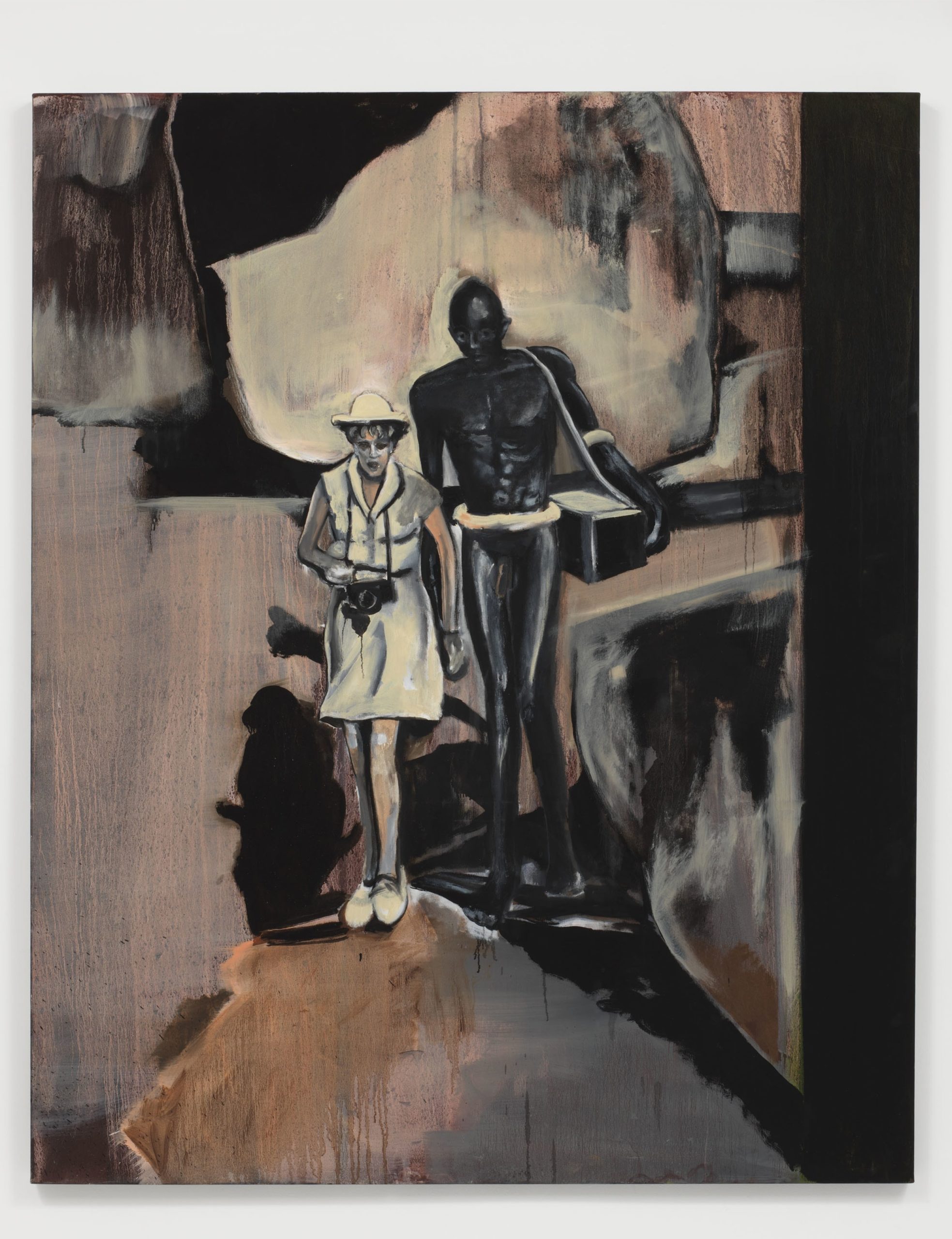

The show is all gems, but several rough diamonds grabbed this writer with special force: The Waiting Room (2008) describes a Victorian parlor with a seated Hans Bellmer doll and two Goyaesque marionettes peeking out from behind a wall of peeling paint; Imaginary Enemy (2009) depicts a masked female (she’s a dead ringer for identikits of the Zodiac killer) and a teacup-headed male figure striding into a Cartier Love Bracelet like a honey bear into a clawed trap; Leni Riefenstahl (2011) features an oil on canvas version of a 1970s photograph of the director of Triumph of the Will walking hand in hand with a Sudanese Nuba warrior. This last image, originally orchestrated as a photograph by the Nazi-era filmmaker as part of her unlikely comeback, Davis turns both jarring and Delphic—it’s equal parts lion lying down with the lamb, and Walter Winchell epithet for Riefenstahl: pretty as a swastika.

© The Estate of Noah Davis. Courtesy The Estate of Noah Davis

Private Collection

© The Estate of Noah Davis. Courtesy The Estate of Noah Davis

That quality of lucid contradiction—in the words of F. Scott Fitzgerald of being able to hold onto two opposite ideas at once without going batty—is key to picture after layered picture with Davis. The very same gift, which the Great Gatsby author further described as “the ability to see that things are hopeless and yet be determined to make them otherwise,” enabled Davis to both conceptualize and bring to life the modest giant of an institution that is The Underground Museum. The gallery bravely attempts to synopsize that great piece of social sculpture into a single room. It’s no easy task. While the items shown there—the video BLKNWS by Davis’ brother Kahlil Joseph, furniture by the artist’s mother Faith Childs-Davis, a sculpture by his talented widow, as well as models of exhibitions Davis curated—capture some of the energy of the institution, it can’t possibly do it justice.

What the viewer is left with is a murmur of the place, voiced by an artistic talent in full display elsewhere: room after room of painted poetry that capture Noah Davis’ polymathic gift, at once mature and promising. It keeps on giving and giving and giving again.

Related Reading

David Zwirner Gallery Website

Kulchur Vulture No.8 Faurschou Foundation: The Red Bean Grows in the South | New York

Kulchur Vulture No.7 Robert Longo : Fugitive Images | Metro Pictures NYC

Kulchur Vulture No.6 Alex Da Corte : Marigolds | Karma NYC