Articles and Features

Stealing Art: When Men Took Credit For Women’s Work

By Tori Campbell

“She did the drawings people think of when they think of Frank Lloyd Wright.”

Deborah Wood

Art Theft through Misappropriation

When we think of art theft we may think of heists: men with black ski masks skulking through dark museums at night. However, some of the most egregious forms of art theft in history occurred in the subtler form of misappropriation.

Arguably by reason of the implicit biases against women, still alive and well, artistic misappropriation often involves cases in which men took credit for women’s work, even when evidence points strongly to the contrary. Looking at an iconic piece, we are hesitant to rewrite the narrative that has been fed to us; comfortable believing what the supposed-artist told us, that the work came from his genius and his friend, wife, or lover would be incapable of such creativity and original thought.

Although we provide several examples here of true histories that have been uncovered for us, due to the very nature of this kind of art theft, there may be many more untold examples of works misattributed over time.

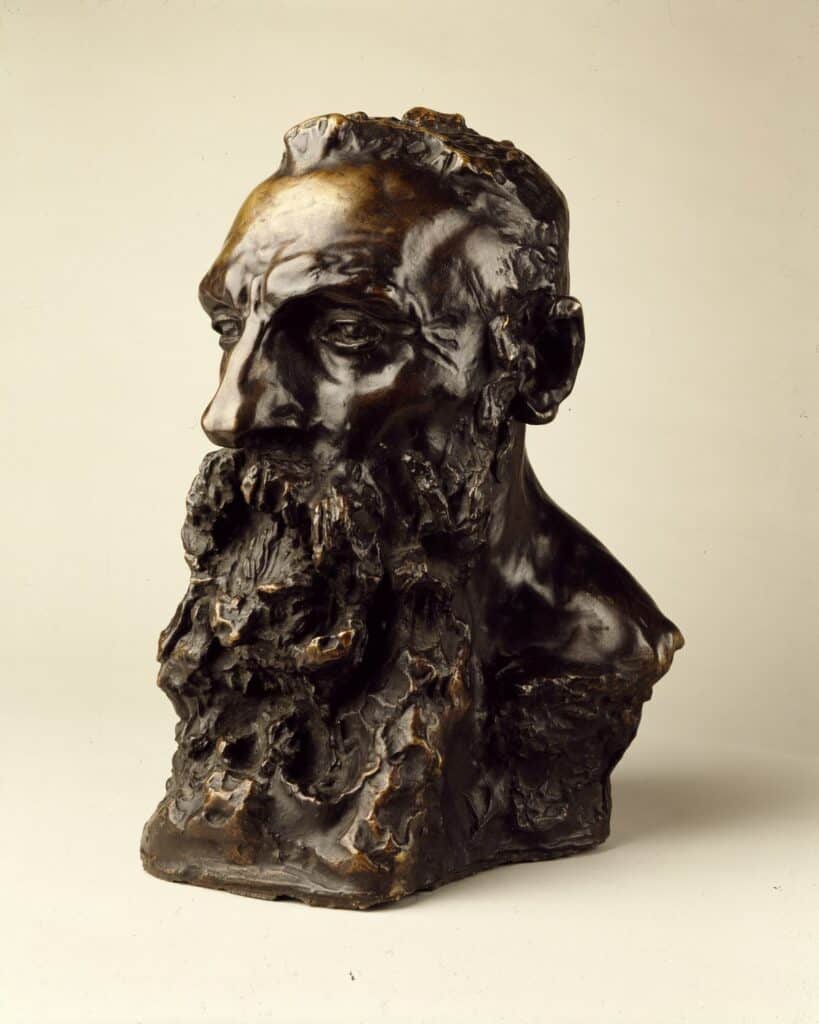

Camille Claudel & Auguste Rodin

At just 19, Camille Claudel came to 42-year-old Auguste Rodin as a student in sculpture. As she was a woman in the late 1800s, she was barred from studying art at formal institutions and instead toiled in a workshop setting, beginning at Rodin’s in 1883. She quickly became a source of inspiration for the artist, acting as his model and muse as well as his lover.

However, due to Rodin’s 20-year relationship with Rose Beuret, their affair would prove to be tumultuous and damaging. Claudel heavily relied on Rodin financially, having been emotionally abused and cut off from the family by her resentful mother.

She worked tirelessly at some of the most demanding aspects of Rodin’s work, such as the hands and feet of the figures on the Gates of Hell; and during this time both of their work grew and flourished. In 1892, after an abortion, Claudel decided to end the physical entanglement of their relationship, though they remained in near-constant contact until 1898.

Unfortunately, after the artists’ sexual relationship ended, Claudel was unable to get the funding for her projects due to sexism in the industry. Thus, she often has to depend on Rodin as a collaborator or have him sign her works in order to be seen or fulfilled. This went on until 1899 when Rodin first saw Claudel’s The Mature Age, which has been interpreted in myriad ways though could arguably be seen as reflecting the love triangle in which the two artists were involved. Rodin responded unfavorably, going so far as to supposedly put the Ministry of Fine Arts to cancel the funding for the bronze commission.

Ultimately, by 1905, it was asserted that Claudel was deeply mentally ill. She destroyed many of her own works and showed signs of what was believed to be paranoia, fearful to make more art as she believed Rodin would steal it from her. She died in loneliness, poverty, and obscurity after living in a mental institution for 30 years, in 1943.

Many decades later, in 2017 the Musée Camille Claudel opened in her hometown of Nogent-sur-Seine. While this museum has salvaged many of her rightfully attributed works, it remains unclear how many sculptures signed under Auguste Rodin’s name and exhibited at museums around the world as such, could in fact be the work of Camille Claudel.

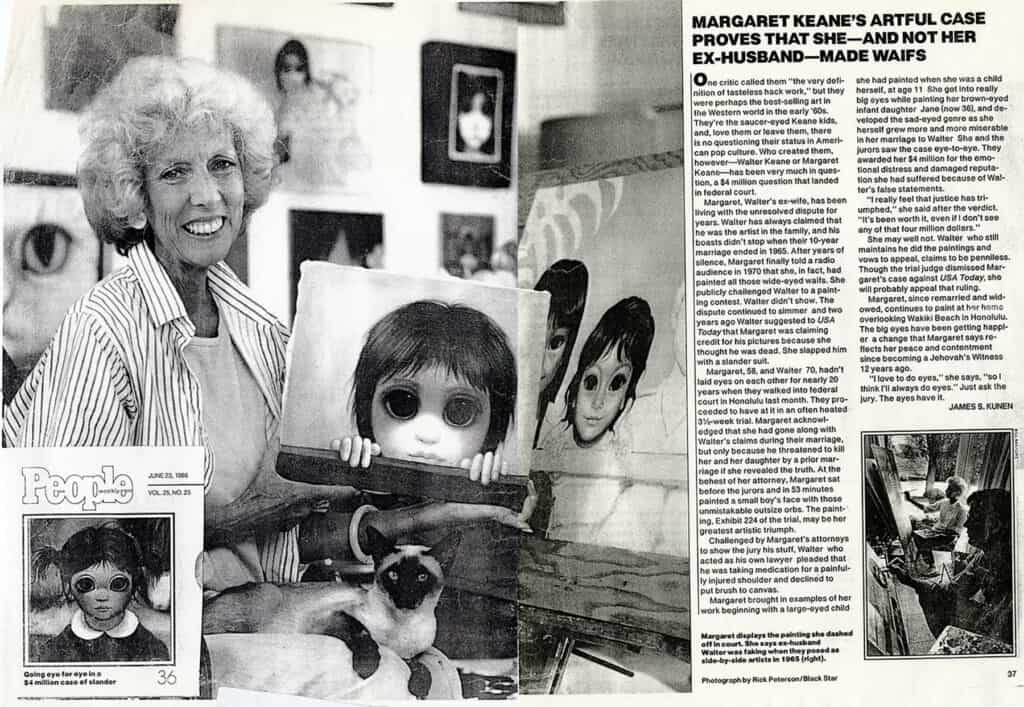

Margaret & Walter Keane

One of the more well-known instances of art theft through misattribution is the case of Margaret and Walter Keane. Margaret Keane’s paintings of women, children, and animals with big eyes achieved commercial success in the 1960s after being extensively reproduced on prints and household goods. Keane’s husband, Walter Keane, had begun selling her paintings as his own without her permission in the 1950s; using threats of violence, emotional abuse, and intimidation to keep her silent. By reason of their innovative yet rather cliche commercial quality, the works gained immense popularity, one which Walter singlehandedly enjoyed while Margaret laboured alone.

In 1965 the two were divorced and by the 1970s Margaret Keane revealed the truth to the public: she was the true artist behind the paintings. Walter denied her assertions, leading to a profoundly dramatic courtroom scene in 1986, in which the two partake in a ‘paint-off’. Walter claimed himself unable to partake due to a sore shoulder, while Margaret easily produced a perfect copy of an earlier work, finally earning what should have been hers all along, the rightful claim to her art.

People Magazine, July 1986

In 2014, director Tim Burton released the biopic Big Eyes, starring Amy Adams and Christoph Waltz as Margaret and Walter Keane, bringing a resurgence of interest in her work and story.

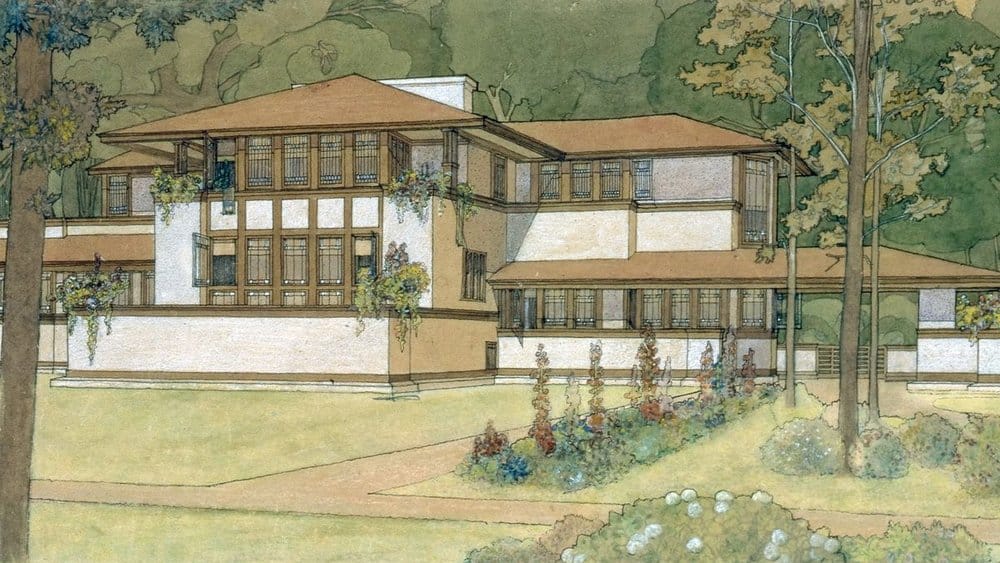

Marion Mahony Griffin & Frank Lloyd Wright

Shortly after graduating from MIT (only the second woman to accomplish this feat) in 1894, Marion Mahony became the first licensed female architect in Illinois.

By 1895, the young architect became Frank Lloyd Wright’s first hire for his new architecture studio in Oak Park. It was here that Mahony was able to encounter and contribute to the center of America’s Prairie style design movement and enjoy the “little university” setting of the office.

Mahony designed buildings, stained glass, decorative panels, and furniture for Wright’s studio; but her largest and most lasting contribution is undoubtedly her stunning architectural renderings. Scholar Deborah Wood has explained that Mahony “did the drawings people think of when they think of Frank Lloyd Wright”.

Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation/Frank Lloyd Wright Trust

Wright consistently understated the contributions of his employees and often took credit for their work. For example, over half of the 1910 Wasmuth Portfolio, a two-volume folio of 100 lithographs is thought to be Mahony’s work, though Wright is the only credited contributor. Though her beautiful watercolour renderings would continue to be misattributed to Frank Lloyd Wright, this work forever shifted the way that architectural renderings would be presented and perceived.

Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven & Marcel Duchamp

Though not immediately popular, Fountain has grown in acclaim throughout the last century and is now considered to be a seminal work of 20th-century art. The readymade sculpture, a porcelain urinal laid upon its back, was submitted for an exhibition for the Society of Independent Artists at The Grand Central Palace in New York City but was rejected. Alfred Stieglitz, a famed photographer, then photographed the work; allowing the piece to be recorded in history (the original has since been lost) and placing Marcel Duchamp as the hero, an artist who, with the submission of this work, birthed conceptual art.

However, it seems fairly unlikely that Duchamp was actually the artist responsible for this work. For one, a 1917 letter Duchamp wrote to his sister Susanne explains “One of my female friends who had adopted the masculine pseudonym Richard Mutt sent me a porcelain urinal as a sculpture.” And, as is immediately apparent, the urinal is prominently and obviously signed: R. Mutt. Duchamp later explained this designation away, saying that he had purchased the urinal from JL Mott Ironworks Company, changing Mott to Mutt – although the company did not manufacture this model of urinals.

With all of this sleuthing, one may reasonably ask himself if it was Duchamp the original artist of Fountain. But then, if not him…who was? Almost without a shadow of a doubt, the true artist of this lauded work was Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. An active figure in the Dada Movement, an avid collector of pipes and drains, and co-creator of God, a sculptural piece made of plumbing. Freytag-Loringhoven also found a rusted iron ring on the sidewalk, and in one instant, dubbing the discarded piece Enduring Ornament, she had become the mother of readymades a year before Duchamp’s Bottle Rack.

There are also myriad theories about why Freytag-Loringhoven would have used the pseudonym R. Mutt, but the most compelling link between the work and the Baroness is the matching handwriting found on both her own poems and the urinal.

Lastly, though André Breton attributed the work to Marcel Duchamp in 1935, Duchamp himself would not publicly take credit for Fountain until 1950 after both Alfred Stieglitz and Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven had died. In 2004, the work was voted the most influential modern artwork of all time, an accolade that carries plenty of weight on its own, but would be extremely meaningful if rightfully attributed to a woman artist.

Even after curator and scholar Glyn Thompson and Julian Spalding have presented the evidence at length for reattribution of the urinal to Von Freytag-Loringhoven, most institutions have steadfastly stuck to the narrative of Duchamp (or “Marcel Dushit” as Freytag-Loringhoven was wont to call him) as conceptual art hero.

The century-long fight to reattribute Fountain to its true artist is indicative of the many struggles that women have faced in order to receive credit for their work. Even when women prevail and receive credit for their work, it is often at great personal and financial costs, like Margaret Keane’s lengthy and expensive legal battle or Camille Claudel’s deteriorated mental state. Though misattributions do not always come from a place of malice or ill-intent, it is worth investigating how and why they are so common, especially with such a profound gender imbalance.

Relevant sources to learn more

This article from The Guardian dives deeper into the case of the Fountain

This snappy timeline from Mother Jones explores misattributions outside of art theft, and across numerous industries