Articles & Features

The Art of Forgery – Art Forgers Who Duped The World

” Only the experts are worth fooling. The greater the expert, the greater the satisfaction in deceiving him. “

Eric Hebburn

Have you ever wondered what makes art really original and unique? Is it the hand that made it or the innate qualities of the work itself?

If a fake Van Gogh appears as beautifully vibrant as an authentic one, enough that not even an experienced eye can tell the difference, why does the art world revolve around the concept of authenticity to such a large extent?

The fact is, every artwork is an unparalleled expression of an individual creative talent and a result of a precise personal, historical and cultural context. Art forgeries, even if aesthetically pleasant or technically stunning, can cause serious misinterpretations with extremely damaging consequences, first of all in the academic field, as well as disruptions to the art market.

But what actually is an art fake? In general, when an artwork is said to be a fake, it is presented as by one artist, despite actually being created by another – and this is not necessarily a crime, as we shall see. Legally speaking, only written documents can be forged so, for example, we could have a fake painting with a forged statement of authenticity. Nevertheless, this technicality does not apply to the everyday and the terms “art fake” and “art forgery” can be used interchangeably.

But there is more, psychological studies have revealed that authenticity also affects the way we look at artworks at a neurological level. Actually, the viewer’s reaction not only changes when he looks at an authentic artwork but also when he observes one that he has been informed is not; basically, our perception is different when an authority figure tells us what we are looking at, a “real” or a “fake”.

” Anyone who believes he can buy a real Giacometti for €20,000 deserves to be duped. The art world is rotten. “

Robert Driessen

The most notorious art forgers

It could easily seem that the main purpose behind art forgery would be financial gain – do not be misled, profit surely plays a huge part and a gigantic amount of money is involved – but it is often the case that human factor has a considerable role, in some instances the desire for revenge against a system that doesn’t seem to recognise the talent of a would-be artist. This is, for example, how the incredible story of one of the most famous art forgers of all time began.

Han van Meegeren (1889-1947) was a mid-level Dutch artist with a penchant for a naturalistic and realistic style in a time when the avant-garde movements were commonplace. It is easy to see why the art critics were not enthusiastic about his work, they recognised his technical talent but found no sign of originality. Out of spite and driven by the desire to humiliate those critics, van Meegeren began to dupe them.

In Vermeer, he found the perfect artist to forge: he was a revered Old Master, little information about his life was available, and it was considered likely that the artist produced many more works than were already known about or acknowledged.

Van Meegeren spent years in Nice developing the ultimate process to create the perfect fake; he gained the right paint, canvasses, wood panels and even recreated a home-made brush similar to the one Vermeer used. He also managed to accelerate the ageing process and create a plausible craquelure pattern. But above all, van Meegeren’s talent was to understand exactly the intangible qualities of a Vermeer that art critics and experts were looking for, providing them with the kind of paintings they were both hoping and expecting to find. When, in 1937, Van Meegeren’s forgery depicting The Last Supper fell into the hands of the collector and Vermeer expert Abraham Bredius not only it was declared as authentic, but as the artist’s seminal masterpiece.

A string of well-concocted hoaxes continued and van Meegeren’s forgeries accumulated to become a trove with an estimated ‘market’ value of $30 million. They were so convincing that they were never actually analysed. On the contrary, we probably would know nothing of this whole story to this day if van Meegeren had not determined to give himself away. In the aftermath of World War II, the Dutch government brought him to trial on charges of conspiring with the Nazis: he had sold, via a third party, Woman Taken in Adultery by Vermeer – a national treasure – to Göring. Reckoning it better to be considered a forger than a traitor, van Meegeren confessed that he had indeed sold the painting to Göring, but that he had not betrayed a heritage icon by Vermeer, but rather a highly accomplished painting he had made himself. Moreover, he claimed to have traded the work for more than a hundred Dutch artworks, saving them from Nazi-looting. The fame he had longed for as an artist was ultimately achieved as a patriot of sorts.

To prove that his statements were true van Meegeren painted a new work, under police supervision, which he titled Jesus Among the Doctors, resulting in the charges of treason being dropped. Instead, he was found guilty of the lesser charge of forgery, dying of heart disease a month after the trial.

The same sentiment of revenge that moved van Meegeren is also what urged the prolific Dutch art forger Robert Driessen. Disillusioned that no one was interested in his paintings, he began to manufacture variations on the works of Expressionists or mirrored obscure versions of originals, eventually evolving his practice to create totally new paintings imitating the style of noted artists. In the late 1980s, Driessen switched to sculpture and eventually found his penchant for Giacometti: “Long, thin figures, and an amorphous, crumbly surface, it isn’t difficult to make Giacometti’s. I literally had Giacometti in my fingers”. Police estimate he forged at least a thousand sculptures but Driessen himself claims it was probably way more. Currently, he lives in Thailand, out of the reach of European authorities, where he produces and sells original reproductions, all of which are signed by him.

” In prison they called me Picasso.”

John Myatt

Selling clear copies after being unmasked is not uncommon for art forgers. This is also what happened to John Myatt, the forger behind what Scotland Yard defined as “the biggest art fraud of the 20th century”. Between 1986 and 1994, he faked around two hundred works by artists like Marc Chagall, Jean Dubuffet, Henri Matisse, and Alberto Giacometti and, with the help of an accomplice, a specialist in generating false provenances, they fooled collectors and experts alike, enough that the works were auctioned for hundreds of thousands of pounds by Christie’s and Sotheby’s. In 1999 Myatt was sentenced to twelve months in prison but served only four for good behaviour. He is now operating openly, and entirely legally, selling what he calls “genuine fakes”.

Among the varied category of art forgers, we can distinguish two major groups, the ones who create replicas of existing artworks and those who create brand new pieces inspired by celebrated painters. To the latter surely belongs Wolfgang Beltracchi, considered “the forger of the century” in one of Germany’s greatest art scandals. Over more than thirty years, together with his wife, he hoaxed collectors, gallery owners, and museums.

The strategy was to “fill the gaps” in the artists’ bodies of work, either inventing new works or creating paintings which were believed to be lost but whose titles were known and no images existed that reproduced them. The couple’s scam came to an end in 2011 when experts discovered traces of titanium white in a supposedly 1914 painting by Heinrich Campendonk, but the pigment did not even exist at that time. One thing led to another and eventually the two were found guilty for forging 14 works of art (dozens of other suspected instances could not be proved) and sentenced to a few years in prison. Nowadays, Beltracchi uses his remarkable artistic talent to create original works that are exhibited in gallery shows.

If anyone can share the title of “forger of the century” with Beltracchi, it’s definitely Eric Hebborn. English born but settled in Italy, like van Meegeren he found himself disdainful of contemporary art and art experts, ending up creating artworks inspired by Renaissance and Baroque artists: Rubens, Breughel, Castiglione, Corot, Mantegna, but also Piranesi, van Dyck, and Poussin. After an excellent artistic training, Hebborn began to work in a conservation atelier and soon became aware of how thin the line between restoration and counterfeiting can be. He kept pushing that line until he found himself creating entirely new paintings on fresh white canvasses: his career as an art forger had begun. Together with his life partner Graham David Smith, Hebborn later opened his own gallery, Pannini, and developed a personal and professional network involving high-calibre art connoisseurs, especially within the British scene. In parallel, he faked hundreds of works, drawings in particular, for an estimated profit of $30 million.

When unmasked in the early 1980s, Hebborn admitted his illicit activity without any accompanying shame: contemptuous of the art world, he had made it a rule, a kind of personal ethical code, not to fool amateurs but just experts and dealers, especially the pompous ones who had the purported expertise to detect a fake. Moreover, he continued to taunt the art establishment, stating that several works in prestigious collections had been manufactured by him; some that were subsequently analysed and proved to be, in fact, authentic. Despite his confession, authorities never prosecuted him for fraud, claiming a lack of evidence. Another of Hebborn’s great tricks was the 1991 publication of his book Drawn to Trouble: Confessions of a Master Forger, A Memoir, which offered lessons in forgery techniques and unveiled the dark side of the art world. A few years later, just after the release of his second book, The Faker’s Handbook, his life tragically ended in violent circumstances; his death is still a mystery to date but film-makers working on a movie about the irreverent forger seem to have found a mafia connection.

Art Forgery and Art Theft

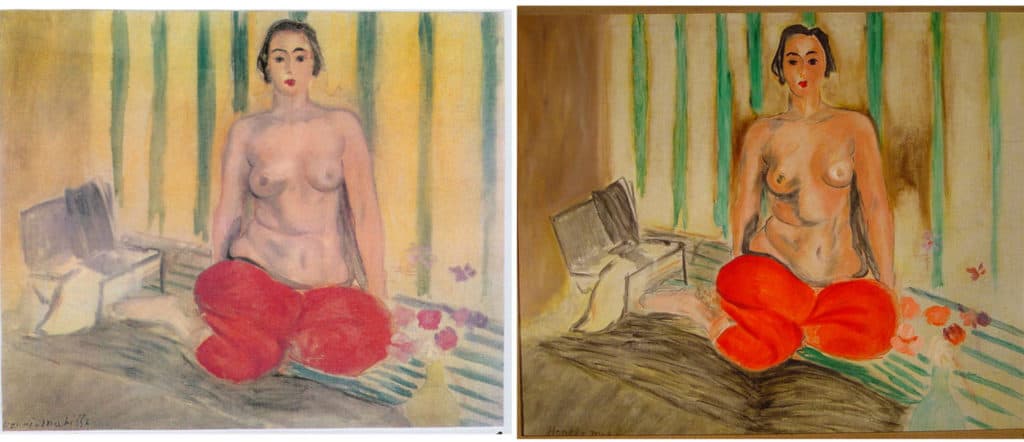

At times, art forgery can be part of larger criminal enterprises, often as a means to abet an accompanying theft of an authentic work, with the intent to replace that work. In 2002 the Contemporary Art Museum of Caracas was contacted by the owner of a gallery in Miami stating that someone had offered him the opportunity to acquire Odalisque in Red Trousers by the artist Henri Matisse which he knew was displayed at the museum. It was only then that the museum staff checked the painting and discovered it had been stolen and switched with a fake, and not even a particularly good one. The forged artwork had been there for at least two years and no one had noticed.

Xiao Yuan, chief librarian at the Guangzhou China Academy of Fine Arts had a similar idea. In fact, since 2004, he has stolen over one hundred and forty Chinese paintings from the very gallery he was custodian of, replacing them with copies he realised himself. He also managed to sell most of the original paintings at auction for around £3.5 million. In defence of his crimes, Yuan claimed that everyone else was doing the same and that he had spotted fake paintings in the gallery since his first day on the job. Incredibly, even after he had concluded the switching, he found out to his surprise that other fake paintings had taken the place of the ones he had himself made: “I realised someone else had replaced my paintings with their own because I could clearly discern that their works were terribly bad”.

But are all art forgers also criminals? In fact, no. In the majority of Western jurisdictions, the act of producing fake art is not a crime in itself, but to pass forged artworks as authentic with the intention of financial gain is the actual offence. The American art forger Mark Landis knows that better than most: he spent around thirty years producing fake paintings, donating them to more than fifty small museums across the United States. He adopted various personas – the most eccentric being Father Arthur Scott, a Jesuit priest dressed all in black who would arrive in a red Cadillac bearing incredible stories as to how his family had come to possess the artworks. He would eventually gift the works, often to honour the memory of non-existent relatives.

Though a Landis’ forgery was first unmasked at the Oklahoma City Museum of Art in 2008, with many more similar revelations since, he has never been charged with a crime since he had never deprived anyone of money. Furthermore, he addressed his donations to professionals who had the expertise to detect his forgeries but still, partly assuming good intentions and partly because of the limited resources, did not.

Nevertheless, there were serious consequences in terms of cost for the small and mid-sized museums that had been fooled, since they had to pay for substantial scientific analysis in order to detect fakes hiding in their collections, and for legal advice as well. Overall, the damage of Landis’ ‘gifts’ is calculated to be around 5 million dollars.

Relevant sources to learn more

Authentication in Art

Robert Driessen website

John Myatt website

Beltracchi: the Art of Forgery – Documentary about Wolfgang Beltracchi

Mark Landis website

Art and Craft – Documentary about Mark Landis