Articles and Features

The Fantastic Women Of Surrealism

By Adam Hencz

I did’t have time to be anyone’s muse… I was too busy rebelling […] and learning to be an artist. — Leonora Carrington

Mysterious creature, desired being, goddess, she-devil, doll, fetish and muse. Women were a central subject in Surrealist art and of the male Surrealist fantasies that dominated the genre. Well-known artists of the movement – including René Magritte, Joan Miró, Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, Hans Bellmer – often portrayed either idealised, fragmented, or grotesque and provoking female bodies as objects of both fear and erotic desire. This may be attributed, at least in part, to the Surrealists’ engagement with Freudian psychoanalytic theories. After André Breton established the philosophical grounds of Surrealism and published a series of Surrealist Manifestos starting in 1924, women slowly developed close ties with the leading writers and painters of the group as muses, models, lovers, companions, and later as active performers. In the 1930s, women joining the Surrealist circles started questioning their own reflection, talking on more active participant roles in the search for a distinct model of female and artistic identity.

Fantastic Women, an ongoing joint exhibition of Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt, in cooperation with Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark, celebrates female artists from around the world that were associated with the Surrealist movement. “The omnipresence of the female body in Surrealist art confronted women artists with the task of growing, with their own ways of seeing and thinking, from a passive object into an acting subject” writes the exhibition’s curator, Ingrid Pfeiffer, in the publication that accompanies the show. On display are also works from lesser-known artists such as Alice Rahon, Eileen Agar, Kay Sage and Ithell Colquhoun besides more famous and iconic cultural figures like Frida Kahlo, Meret Oppenheim, Leonora Carrington and Dorothea Tanning. The exhibition surveys a wide range of styles and subjects encompassing more than 260 paintings, drawings, photographs, collages, sculptures and film by 34 artists from 11 countries.

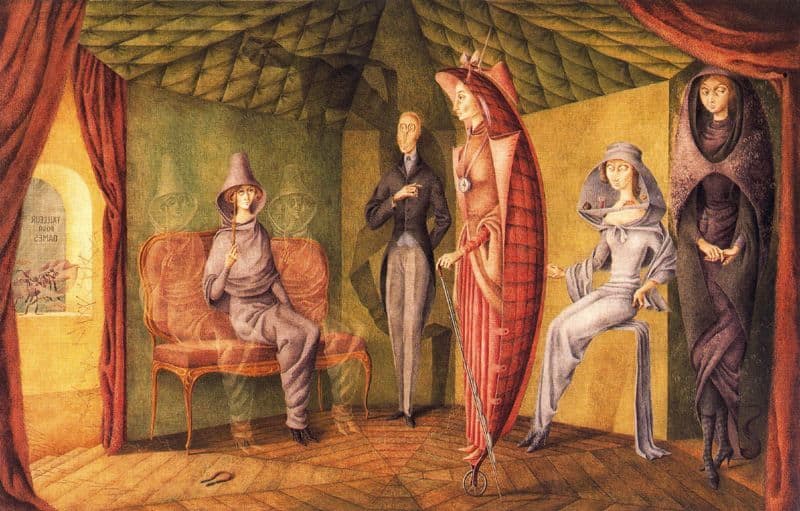

Many of the most well-known Surrealist women became involved with the movement through their personal relationships. Meret Oppenheim and Lee Miller both worked with Man Ray, in addition to making their own Surrealist works. Leonora Carrington and Dorothea Tanning became involved with Surrealism through Max Ernst and Remedios Varo through the Surrealist poet Benjamin Péret. The female Surrealists were typically younger than their male colleagues, initially in thrall to them, and through an emancipation of sorts to independence went on to create many of their main works in the 1940s and 1950s. Although the Surrealist group continued to organise exhibitions until the 1960s and was only dissolved in 1969, many art-historical observers have claimed that Surrealism ceased with the end of World War II. This view in fact bears some of the blame for the lack of attention given to the female artists who flourished after the common, and somewhat misplaced consensus, as to what constituted the movement’s heyday.

A new model of female and artistic identity

The female Surrealists rebelled against gender-specific role behavior and often represented themselves with strikingly androgynous features or in unusual roles or disguises. French artist Claude Cahun is best known for her self-portraits assuming a variety of personae. She developed photographs as well as a number of photo montages already in the 1920s. Her highly topical series of self-portraits addressing gender roles remained almost unknown for a long time.

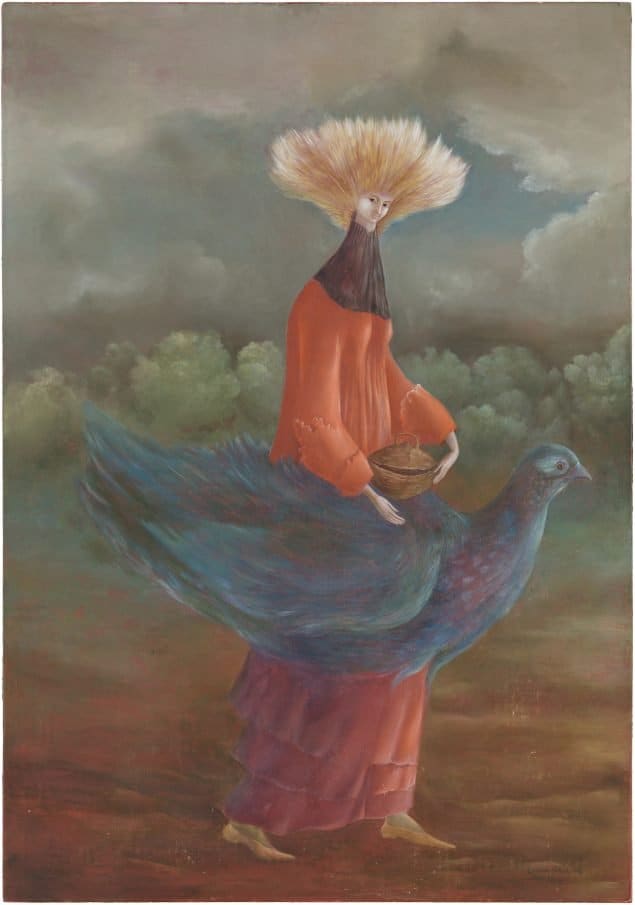

Argentinian born painter Leonor Fini was a virtually self-taught artist whose provocative art and vivacious personality quickly garnered her a spotlight in the Parisian art world. She reversed gender roles, giving her women subjects unprecedented sexual prowess and agency, while men were often depicted passive. Her strong female characters are often mystical and hybrid, half human and half mythological beings, women with a resolute gaze often protecting, looking after men, and showing, leading them the way. In addition to her paintings, she created many stage and costume designs for opera, ballet, theatre and film, while also arranging her own exhibitions.

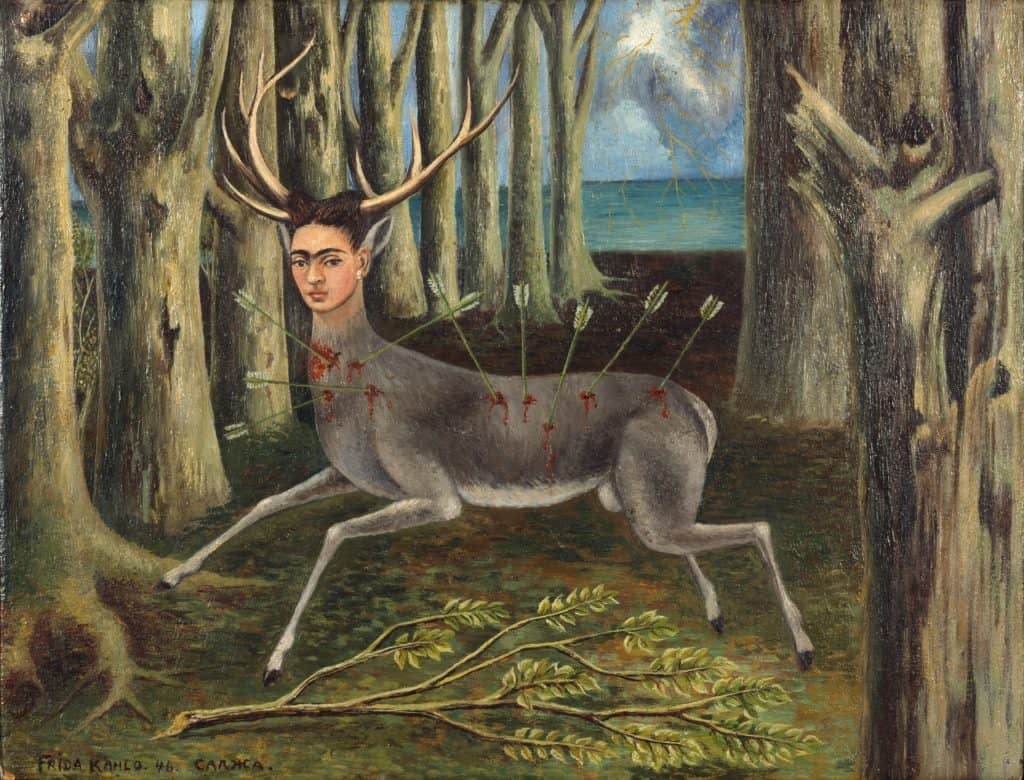

Mexico as a place of exile

1939 marks an important year in the history of Surrealism, as this was the year when Frida Kahlo exhibited in Paris as a part of a group exhibition called Mexique. A year earlier André Breton and French painter Jacqueline Lamba took a trip to Mexico where they met Kahlo and her husband, artist Diego Rivera. Although Kahlo and Rivera were never officially part of the Surrealist circles, they are often associated with Surrealism because of their predilection for finding impulses from the subconscious and dreams and for the rich symbolism of their works. “They thought I was a Surrealist, but I wasn’t,” Kahlo said, “I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality.”

In Paris, Kahlo was also introduced to French poet and artist Alice Rahon, as well as the Spanish painter Remedios Varo. The two women later settled in Mexico with their husbands. The increasingly commonplace transplanting of European exiles into the cultural milieu of Mexico City of the 1930s and 1940s breathed a new life into the vibrancy of these circles. In the 1940s Leonora Carrington also emigrated to Mexico and developed a close friendship with Remedios Varo, her intellectual and spiritual kin. While Carrington and Varo shared subject matter based on the universe, the supernatural, alchemy, and astrology, they interpret these topics differently in their works.

Political reflections

Photography offered women Surrealists many opportunities to distort and question the representation of reality through retouching, subsequent coloring, montages, and extreme exposures. A central member of the post-war Czech Surrealist group, Emila Medková focused on the irrationality of the urban environment, finding metaphors for the oppressed post-war central Europe.

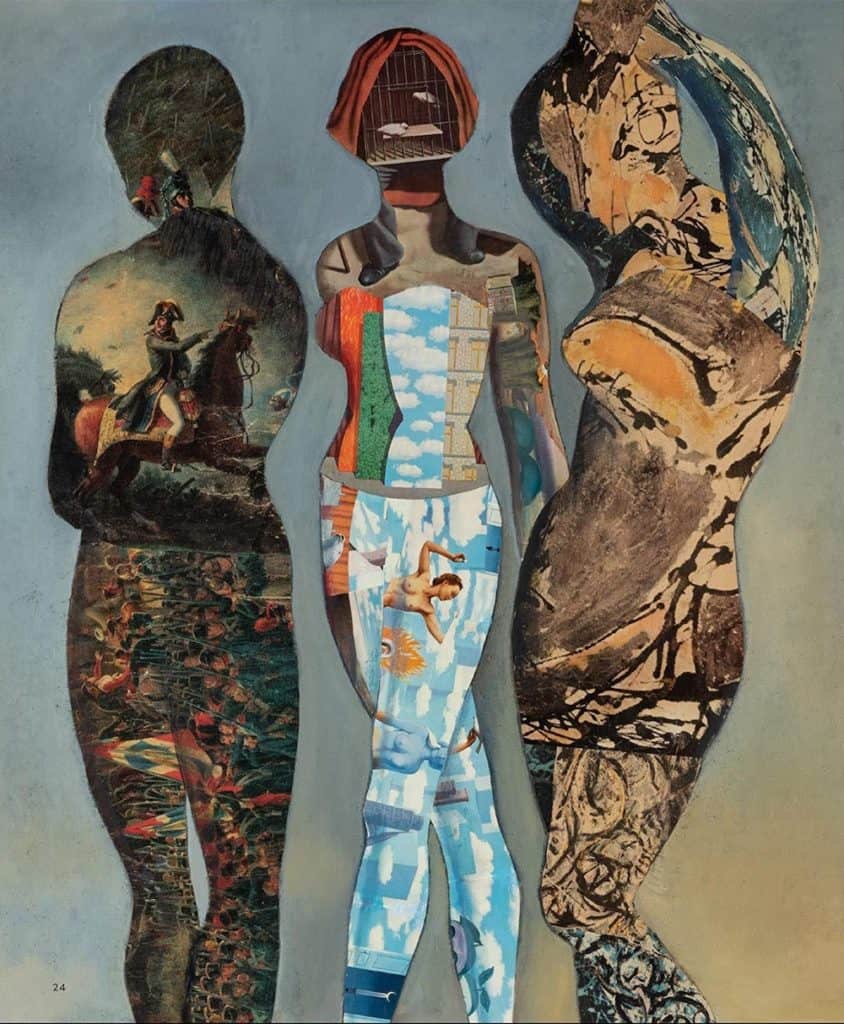

Belgian Surrealist painter Jane Graverol additionally employed collage technique to juxtapose conflicting elements, and critically questioned traditional structures such as the patriarchal, imperialist model of society. It was not unusual for a Surrealist artist to also be overtly political. Among women of Surrealism, photography served as a means of asserting a politicised position most often in imagery redolent of social critique. The works of Dora Maar constantly reflected on contemporary events, challenging the idea of the modern woman, and, as a street photographer she was often depicting those who had been thrown into poverty by the Great Depression.

Some of the women artists were only briefly affiliated with Surrealism, and their contribution to the movement appears to be limited to a short period of time. After her accidental rediscovery of the photographic technique of solarization and short period engaging in Surrealist perspectives, Lee Miller, as an example, embarked on a new career as a photojournalist and war photographer. Sheila Legge immersed herself in Surrealist practice for several months. On the opening day of the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition in London, she dressed as the Surrealist Phantom performing in front of the Trafalgar lions and Claude Cahun’s camera, with her head completely obscured by a floral arrangement.

Analysing dreams, expressing the subconscious through dreamscapes, embracing creative practices like automatic drawing, creating works revolving around chance, metamorphosis, political events, philosophy and myths, are elements one can find in almost all Surrealist works, whether made by a man or a woman. The biggest difference between the genders can be characterised by how they saw and depicted themselves. The women of Surrealism were searching for a new female identity and in the meantime developed their own language of forms and symbols to do so. They wanted to be perceived and evaluated irrespective of their gender and were highly flexible with their stylistic choices toward this end. The male culture of self-depiction focused on egocentric representations of desire, and for as long as the male artists were considered the principal protagonists of the movement, this came to be regarded as the predominant theme or leitmotif of the Surrealist project. The nuance of the women’s various outputs, the playful and self-confident approach to their body image, not to mention the sheer volume and diversity of women within Surrealist circles, both expanded Surrealist practice and extended the longevity of its movement and themes in ways that have been long overlooked.

Relevant sources to learn more

Fantastic Women at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art

Art Movement: Surrealism

Women Of Surrealism on Artland: Meret Oppenheim, Leonora Carrington