Articles and Features

The Gallery of Lost Art.

The Erased Archive of Art You Will Never See

By Shira Wolfe

“The Gallery of Lost Art was an immersive, online exhibition that told the stories of artworks that had disappeared. Destroyed, stolen, discarded, rejected, erased, ephemeral – some of the most significant artworks of the last 100 years have been lost and can no longer be seen.”

Tate

Either destroyed, stolen, discarded, rejected, erased, or ephemeral by nature, some of the most significant artworks of the past 100 years have been lost forever, and can no longer be experienced in the flesh.

For this reason, in 2012 the Tate initiated a project called The Gallery of Lost Art – an immersive, online exhibition that told the stories of disappeared artworks. The virtual yearlong exhibition explored the circumstances and stories behind the loss of some major works of art by over 40 artists including Marcel Duchamp, Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró, Willem de Kooning, Rachel Whiteread and Tracey Emin. Viewers could wander through a virtual warehouse space and explore the stories of lost artworks through films, sound clips, digital images, documents and links to other resources. After a year, fittingly, the website itself was ‘lost’ and taken down. A full-length book by Jennifer Mundy titled Lost Art remains, compiling expanded narratives about the different case studies. What follows are a few of the most compelling ‘lost art’ stories.

Francis Bacon’s Study for Man with Microphones

In 1946, Francis Bacon completed Study for Man with Microphones, a painting depicting a public orator who appears to be caught mid-sentence. He exhibited the work twice that year, then reworked the painting at some point over the course of the next 15 years. In 1962, the painting was exhibited in its revised form as Gorilla with Microphones. The microphones from the original painting remained, but the man seated under an umbrella had been replaced with the truncated torso of a nude with its back to the viewer, head and face distorted. However, Bacon was still not satisfied. Two years later, the painting was listed as ‘abandoned’ in a catalogue raisonné of his work and the only known image that remains of the original Study for Man with Microphones is a black and white photograph reproduced in one of the 1946 exhibition catalogues.

Bacon was notorious for having trouble knowing when to stop working on his canvases. Often, they became so filled up with pigment he would have to discard them. He also destroyed works that he wasn’t satisfied with. After Bacon’s death in 1992, almost 100 slashed or destroyed canvases were discovered in his studio. Among these works was Gorilla with Microphones, with two large sections cut from the centre of the canvas. Despite these slashes, the painting reveals Bacon’s approach to art very well. He once even commented that his destroyed works were among his best, admitting that he often regretted losing them.

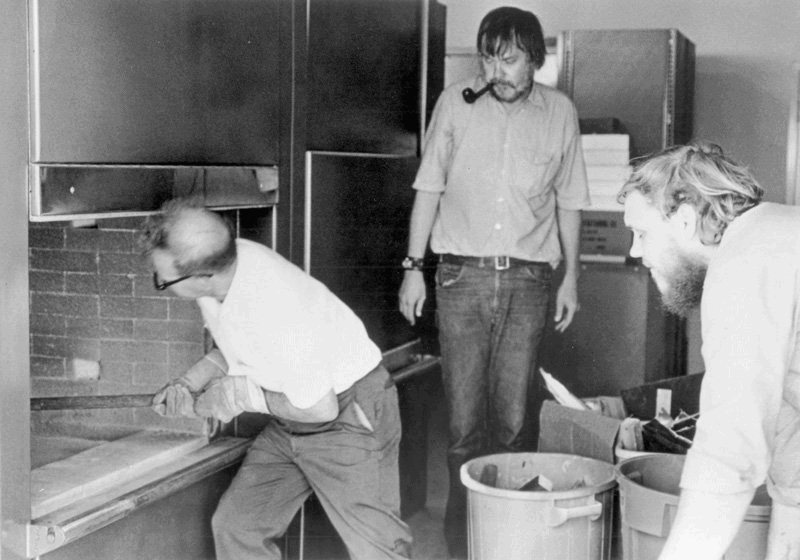

John Baldessari’s Cremation Project

On 24 July 1970, John Baldessari burned all his paintings made between May 1953 and March 1966. These dates marked the moments he had started and stopped painting in a more traditional sense. From 1966, Baldessari started moving more and more towards the conceptual realm, incorporating photography and text in his canvases. He started to wonder about the vast number of paintings in his studio and wished to explore art beyond painting.

In his writings from that period, Baldessari notes: “The world has too much art – I have made too many objects – what to do? Burn all my paintings, etc., done in the past few years. Have them cremated in a mortuary. Pay all fees, receive all documents. Have event recorded at County Recorder’s. Send out announcements? Or should it be a private affair? Keep ashes in urn.”

And so Baldessari decided to make an artwork out of his desire for a fresh start in art. He found a crematorium owner in San Diego who agreed to incinerate his artworks in a furnace usually used for human cremations. David Wing documented the process for Baldessari as part of the Cremation Project. The project, involving the destruction of 13 years of work in one go, proved to be highly emotional and conceptual, posing the question of whether it mattered if artworks no longer exist materially. Baldessari was interested in exploring questions such as: “Where does art reside? Is it physically there in that painting? Is it in my head? Could it be a trace memory? Could it be a photo? What is necessary for it? Can you just talk about it?”

The process of the Cremation Project was made to feel like a human cremation every step of the way. The ashes of the paintings were placed in several boxes normally used for human remains, while Baldessari also kept a portion of the ashes in an urn that looked like a leather-bound book. Baldessari announced the demise of his paintings in the local newspaper, in order to stop himself from returning to painting as a comfortable and safe technique. The Cremation Project marked a real turn in Baldessari’s career, and its literal creation of the death of painting made this work of art a landmark in the history of conceptual art.

“For me the Berlin Wall was probably one of the most successful media events I ever did. The whole reason almost for doing the wall was more for the idea of doing it and almost as a gesture more than it was to actually paint a wall.”

Keith Haring

Keith Haring’s Berlin Wall Mural

In 1961, the East German government erected a barbed wire fence, and then a concrete wall with watchtowers and anti-vehicle trenches in order to prevent East Germans from escaping to the West by physically separating the areas. As a result, families and friends were separated, and the Berlin Wall became a powerful symbol of the iron curtain which separated East and West Europe. Between 1961 and 1989, around 100 to 200 people were killed trying to escape over the wall. The destruction of the Berlin Wall began on 9 November 1989 but some parts of it – left as a commemoration of those trying times – are still visible and have become an open-air museum. Countless artists and everyday citizens, in fact, left their mark on the wall at one point or another. Among these people is the famous street artist Keith Haring.

In 1986, the Director of the Checkpoint Charlie Museum invited Haring to paint a mural on a section of the wall. Haring enthusiastically accepted the invitation and completed his mural of nearly 100 metres long in a day. He used the colours of the East and West German flags in order to symbolise the bringing together of the two peoples. Haring worked without any sketches and without assistants, creating interlinked figures stretching across the 100 metres of the wall. He later recalled of the experience:

“When I started to paint, the East Germans were peering over the wall all the time. At first they were curious because they saw all the people, sort of milling around on the western side and the press and things, so they didn’t know exactly what I was going to do. But eventually after they came out a few times and realised that what I was painting was not really derogatory or insulting them in any way, they just decided to let me alone and stayed behind the wall the rest of the time.”

The mural was publicized and promoted by the Checkpoint Charlie Museum and Haring himself. Knowing from the start that the mural would not be permanent, he valued more the gesture itself than the actual painting on the wall. That same night the mural was completed, someone painted large sections of Haring’s mural grey. Soon after, other artists and graffitists followed suit and started painting on Haring’s section of the wall. After three months, very little was left of Haring’s mural, and after the fall of the Berlin wall, all that remained of it was in people’s memories and photographs. But this did not bother Haring, who said of his art:

“It is temporary and its permanency is unimportant. Its existence is already established. It can be made permanent by the camera.”

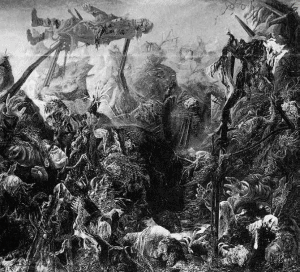

Otto Dix’s The Trench

As a young man in 1914, German artist Otto Dix voluntarily joined the German army and fought for four years in the trenches during the First World War. During these war years, Dix made many sketches of life in the trenches. Expressionist in style, the works attempt to capture the violent energy of war through anonymous characters. Several years after the war had ended, Dix decided to tackle the intense subject of the war experience, which he feared was already fading within the consciousness of post-war society. This time, he decided to depict the experience of recognisable individuals in gruesome detail. In order to refresh his wartime memories of dismembered and maimed bodies, Dix visited mortuaries and dissecting rooms, and then set to work on his painting The Trench (1920-23), which became a monumental piece: over two metres wide canvas filled with mangled corpses, smashed skulls, worms and maggots. It took him three years to complete the painting.

The painting evoked intense reactions from the public and critics. Some people felt it provoked an anti-war sentiment that might weaken people’s inner war-readiness, or were simply so disturbed and sickened, arguing people didn’t need or want reminders of the war. Though no one could argue with the brilliant realism of how Dix depicted the trenches, many found the detail and the immediacy unacceptable in the context of an oil painting, highly elevated in cultural status. The director of the Cologne museum who had purchased and shown the work was forced to resign, and the painting was returned to Dix in 1924.

The painting had by then become an important symbol of the anti-war movement and was included in the Nie wieder Krieg! (No More War!) touring exhibition in 1924. In 1928, the Dresden art museum purchased The Trench, and it disappeared into storage. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, Dix was fired from his position as Professor at the Dresden Art Academy and was temporarily banned from showing any work. The Nazis included The Trench in their Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich in 1937. The works in the exhibition were presented as expressions by those who were mentally ill, perverse or unpatriotic. After this exhibition, the painting was long thought to have been burned in 1939 along with hundreds of other artworks the Nazis burned. However, it appears that the painting was in fact sold by the Nazis to an art dealer in 1940. What happened to the painting after that is not clear. Most likely, it was at some point destroyed.

Today, The Trench is known only through a number of black and white photographs, which despite the bad quality show the work’s powerful and monumental nature.

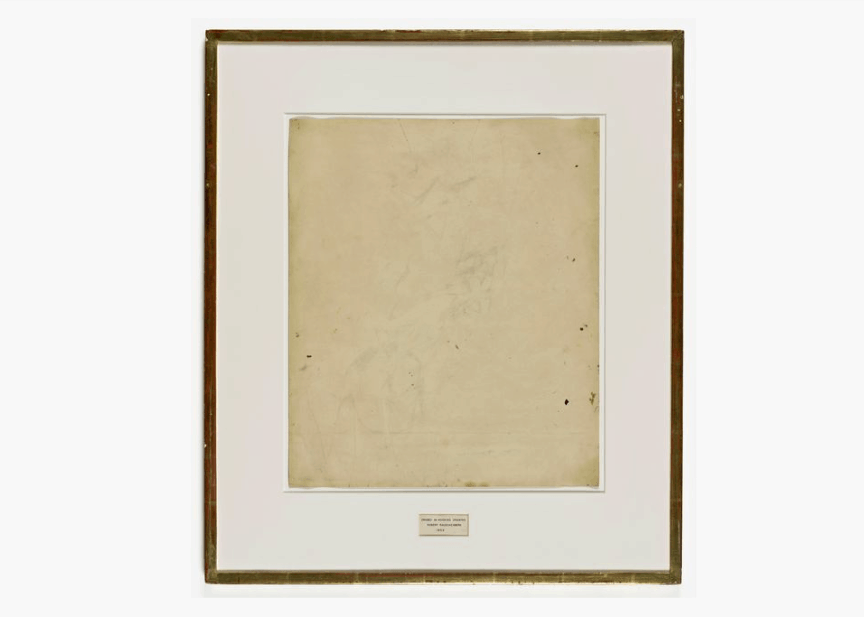

Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing

In the autumn of 1953, Robert Rauschenberg, 28 years old at the time, embarked on a new passion project: he wanted to explore an idea he’d had involving the erasure of an already existing artwork by one of the most highly regarded abstract expressionist artists at the time. He stated at the time: “I had been working for some time at erasing, with the idea that I wanted to create a work of art by that method… Not just by deleting certain lines, you understand, but by erasing the whole thing. If it was my own work being erased, then the erasing would only be half the process, and I wanted it to be the whole. Anyway, I realised that it had to be something by someone who everybody agreed was great, and the most logical person for that was de Kooning.”

De Kooning’s star was on the rise at the time, and Rauschenberg had known him and idolized him for several years. He visited de Kooning’s studio with a bottle of whisky and set out to explain his idea. At first, de Kooning kept bringing the notion of destruction up, and Rauschenberg in turn kept trying to explain that the work would not be destroyed. At first, de Kooning was not too pleased with the idea, but after some time he began to understand what Rauschenberg was after, and agreed but decided to make it difficult for Rauschenberg by giving him an artwork that he would actually miss.

Rauschenberg had been actively testing the boundaries and definition of art. With his White Paintings, a series of plain, all-white canvases, he had paired painting down to an absolute minimum. Next came the Erased de Kooning Drawing, as a kind of extension of the White Paintings. With the project, Rauschenberg posed the question whether a work of art could still mean something when completely effaced by a third party.

The act of erasure itself proved difficult. It required several weeks of work, and many types of erasers, to remove all of the original drawing. “In the end it really worked,” he later said. “I liked the result. I felt it was a legitimate work of art, created by the technique of erasing.” The work was first exhibited in 1963 and was passionately discussed all over the art world. Rauschenberg was satisfied: he felt a new work had successfully been created by this act of erasing the original work.

Relevant sources to learn more

Discover other stories of lost artworks on the Gallery of Lost Art website

Watch videos about various lost artworks on the Gallery of Lost Art on Vimeo

You may also like:

Lost Architecture. Iconic Buildings That No Longer Exist

Portraits of America: Keith Haring’s Crack is Wack Mural

Frida Kahlo’s “The Two Fridas”