Articles & Features

The Life and Legacy of the Spiral Group

By Shira Wolfe

“The Spiral collective coalesced during the remarkable period of American history that followed the emergence of Martin Luther King Jr. as a national leader of the Civil Rights Movement. The artists in the group were moved to gather to discuss their own engagement in the struggle for Civil Rights, and each resolved the question of engagement in a different way.” – Birmingham Museum of Art

Initiated by Romare Bearden, Norman Lewis, Charles Alston, and Hale Woodruff, Spiral was a black artists’ collective initially formed as a response to The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in August 1963. The artists came together to discuss their own role in the civil rights movement, the shifting landscape of American art, culture and politics, and to consider the role of the artist in the fight for social justice.

The group comprised 15 members in total, with the ages of members ranging from 28 to 65 years old. The members included Emma Amos (the only woman in the collective), Calvin Douglass, Perry Ferguson, Reginald Gammon, Felrath Hines, Alvin Hollingsworth, William Majors, Richard Mayhew, Earl Miller, Merton D. Simpson, and James Yeargans. Although the Spiral collective disbanded after just two years, the conversations, explorations, and developments that occurred during this time had a big impact on all of the members and remain important to this day.

Spiral – Common Ground and Different Opinions

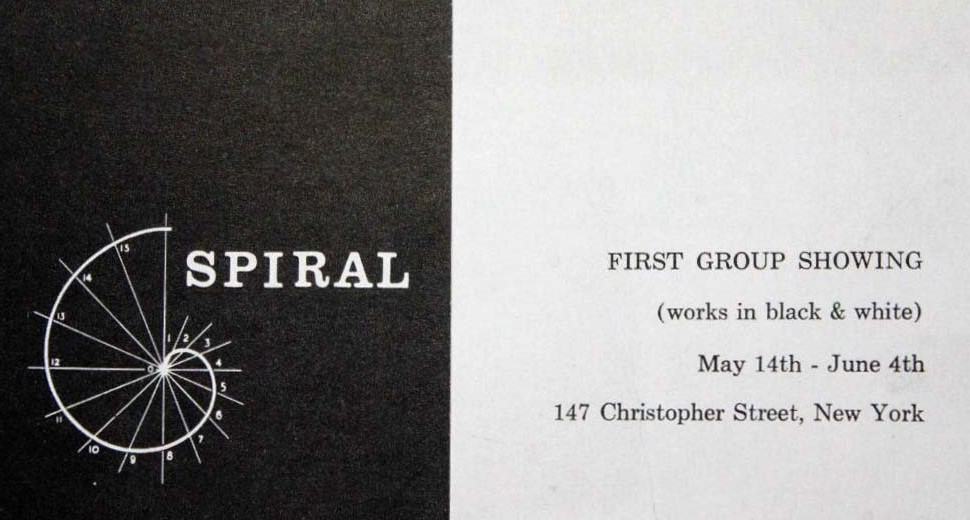

Spiral was formed on July 5, 1963. The name was inspired by the Archimedean spiral, symbolic – with all its spikes radiating outward – of the group’s varied artists and their many different styles, yet containing this common core purpose. The group held weekly meetings at their space on 147 Christopher Street in Greenwich Village, discussing aesthetics, black identity in a mostly white art world, and questions surrounding responsibility to the community and participation in the fight for social justice versus artistic freedom. Many of the artists had moved from the South to New York and felt compelled to engage in the civil rights movement as artists. Together, they explored the different ways to go about this and asked themselves complex questions such as what the role and sense of abstraction were in relation to more social concerns. Norman Lewis was named chairman, and Romare Bearden secretary-treasurer.

The Spiral group’s ethos was one of inclusivity, embracing and encouraging a wide variety of styles, rather than pushing for a common style or approach. Many of the artists associated with Spiral had started out doing figurative work then moving towards a modernist abstract style, but there were also those who worked more figuratively. The types of media the artists employed ranged from oil paint and watercolour to collage and printmaking.

As leaders of the group, Lewis and Bearden had quite different perspectives and opinions. Lewis believed in the political power of abstraction, reckoning that mirroring social conditions was not an effective agent of change. Bearden, on the other hand, had explored abstraction in the ‘50s and was starting to reintroduce figuration into his work in the ‘60s. He started experimenting with collage for the first time during this Spiral collective period. According to Emma Amos, Bearden came in one day with a pile of magazine and newspaper clippings. He wanted the Spiral members to participate in the creation of a collective collage work, but nobody wanted to do it, so he started working on his own. Combining photographs of African masks and faces with subject matter from the African American community, Bearden started making stunning collage-works that became an important element of his body of work, offering him the opportunity to deconstruct, fragment, improvise, and reconstruct– an approach similar to the improvisational techniques of jazz musicians.

“If possible, in these times, we hoped with our art to justify life… to use the black and white and eschew other coloration.” – the Spiral Group statement

The Spiral Group’s First and Only Exhibition, and Disbandment

Spiral’s first and only exhibition was held at their Christopher Street space from May 14 to June 24, 1965. For the show, titled First Group Showing: Works in Black and White, each artist contributed a work in black and white, as a metaphor for the issues they were discussing. The exhibition catalogue contained the following statement from the Spiral artists:

“We, as Negroes, could not fail to be touched by the outrage of segregation, or fail to relate to the self-reliance, hope, and courage of those persons who were marching in the interest of man’s dignity. …If possible, in these times, we hoped with our art to justify life… to use the black and white and eschew other coloration. …This consideration, or limitation, was conceived from technical concerns, although deeper motivations may have been involved. …What is most important now, and what has great portent for the future, is that Negro artists, of divergent backgrounds and interests, have come together on terms of mutual respect. It is to their credit that they were able to fashion art works lit by beauty, and of such diversity.”

Though the exhibition was a success, the Spiral group disbanded in 1965, just two years after it was formed. After the landlord more than doubled the monthly rent on their meeting-and-exhibition space, the members could no longer cover the cost. Moreover, it had become clear that the strong differences in style, approach, and thought among the group’s members could no longer fit together. Still, the importance of these artists coming together to share their different opinions and engage in complicated dialogues about art, politics, philosophy, social justice, and the role of the black artist in America cannot be understated. Usually, the most difficult conversations are the ones most worth having.

The Legacy of the Spiral Group

While many of the Spiral artists ended up making a name for themselves in the art world, exhibiting widely in New York and across the United States, others did not experience commercial success or even left the art world, focusing on teaching or other pursuits. Richard Mayhew, the only surviving Spiral member and now 96 years old, found himself on the sidelines for decades, perhaps due to the fact that he mostly paints landscapes and people did not know where to place him. Only recently, a show at ACA Galleries presented an exhibition of Mayhew’s works to celebrate the publication of his first artist monograph. For decades, little attention was given to Spiral together as a full collective entity, and the first comprehensive exhibition about the Spiral collective, Spiral: Perspectives on an African-American Art Collective, was organised by the Birmingham Museum of Art in Alabama from 2010-2011, then travelling on to the Studio Museum in Harlem, New York.

The Birmingham Museum of Art’s exhibition brochure encapsulates the importance of the group in the following statement: “The Spiral collective coalesced during the remarkable period of American history that followed the emergence of Martin Luther King Jr. as a national leader of the Civil Rights Movement. The artists in the group were moved to gather to discuss their own engagement in the struggle for Civil Rights, and each resolved the question of engagement in a different way. Some created work that directly reflected the urgent concerns facing the black community in American society. Others responded more broadly, some with direct or indirect references to Africa as a source [of] empowerment. Although the collective eventually dissolved, its formation allowed for a shared response to the enormous energy and courage that marked the struggle for civil rights in the early 1960s. The paintings that remain allow us to consider the visual response of African-American artists to one of the most pivotal points in U.S. history.”

According to Richard Mayhew, the Spiral group never really ceased to exist, but rather took on another form through the discussions among African American artists all across the United States today.

Relevant sources to learn more

Lost (and Found) Artist Series: Norman Lewis

Giving Back: Black Artist Community Initiatives Are Creating Opportunity