Articles & Features

The Shows That Made Contemporary Art History: This Is Tomorrow

“The artist in the 20th-century urban life is inevitably a consumer of mass culture and potentially a contributor to it”.

Richard Hamilton

There are multiple ways to delve into the fascinating world of contemporary art. One may consider the development and succession of different artistic movements; the personalities of the major players in the field; not to mention the most iconic artworks that have defined our era. But why not consider the history of art exhibitions themselves? Landmark shows of the modern and contemporary period have impacted and shaped the course of art history, both launching entirely new genres and shaping the history and habits of exhibition-making through innovative practices.

This is indeed the case for the historic This is Tomorrow, a groundbreaking exhibition in several respects. Held at the Whitechapel Gallery in London in 1956, not only did it introduce an innovative collaborative as well as cross-disciplinary practice, but also extended the boundaries of contemporary visual culture by kick-starting British Pop. Although Pop Art is generally associated with the United States – one immediately thinks of Warhol and Lichtenstein – the movement found an early voice in Britain as a critical and ironic reflection on the post-War consumer culture of the late 1950s, and This is Tomorrow served as its key starting point.

“Yesterday’s tomorrow is not today, so maybe today’s tomorrow won’t be quite what you expected…”.

This is Tomorrow

The background

In 1952, in a country simultaneously recovering from World War II – post-war rationing would continue until 1954 – and entering the mass media-dominated Age of Boom, a group of British artists, writers, and critics began to meet regularly at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) driven by a common perception of a gap between the art and life of the time: neither of the two seemed to have anything to do with the other. The collective, come to be known as ‘Independent Group’ – or simply ‘IG’ – rejected the dominant modernist tendency, considered elitist and detached from reality, and therefore used to discuss new theories and practices to incorporate in the artistic practice those aspects of visual culture that weren’t traditionally part of it but that had inevitably become elements of the everyday life, from advertising and glamour magazines to science fiction and comic book characters.

In the same years, new architectural approaches were emerging in relation to the post-war reconstruction projects and, when architect, and critic Theo Crosby began to attend the IG meetings, he was impressed both by the group’s think-tank dynamic and by the debate about the impact of popular culture and mass communication on fine art, design, and architecture. It was him, in fact, who came up with the idea of a multi-disciplinary exhibition that would re-set art, in all its aspects, in a contemporary time-perspective. At Crosby’s request, curator Bryan Robertson, then director of the Whitechapel Art Gallery, agreed to host the exhibition. Thus, after almost two years of heated debate and organisation with limited resources, the show opened its doors, marking a watershed event in post-war British art and culture.

The show

The thirty-eight participants to the show were divided into twelve multidisciplinary groups of three or four people – in principle an artist, an architect, and a designer or a theorist – and invited to work together towards the production of a unique installation on the theme of ‘modern’ living. Crosby himself collaborated with graphic designers Germano Facetti and Edward Wright, and sculptor William Turnbull, in what he later defined as his “first experience at a loose, horizontal organisation of equals”.

The teams would work separately but then display the outcome of their project in the same interactive space, transforming the Whitechapel Gallery into a vibrant and multi-sensorial environment. Moreover, each group would contribute six pages to the catalogue designed by Edward Wright, and design and print a poster to promote the show. Many among those have become iconic and are today part of the Victoria and Albert Museum’s collection.

Despite the limited budget – £50 were the amount allocated to each project – the artists collaborated enthusiastically with an excited glance at the future, merging their individual approaches to develop a new, forward-looking methodology rather than finished artworks. The thousands of visitors who went and saw This is Tomorrow from August 9 to September 9, 1956 were impressed by the endeavour to define a new art for a new world; an attempt inevitably derived by the IG’s reflection on how the communication revolution and its ephemeral quality had impacted visual culture.

As Lawrence Alloway, one of the participants as writer and theorist, stated: “movies, science fiction, advertising, pop music… We felt none of the dislike of commercial culture standard among most intellectuals, but accepted it as fact, discussed it in detail, and consumed it enthusiastically. One result… was to take pop culture out of the realm of escapism, entertainment, and relaxation, and treat it with the seriousness of art”.

Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?

Among the twelve installations, those conceived by Group 2 and Group 6 drew the most attention. The latter was composed of the artists Eduardo Paolozzi, the photographer Nigel Henderson, and architects Alison and Peter Smithson, and presented a project titled Patio and Pavilion: a shelter-like structure in low-quality wood, surrounded by a sand patio, and covered by a plastic roof. Inside, an arrangement of found objects alluding to the human activity – bike parts, a clock without hands, a sculpture – constituted what has been described as a “conglomeration of references”. The couple of architects designed the intentionally precarious pavilion, reminiscent of many huts crowding the cities in the aftermath of the war, while Paolozzi and Henderson took care of the interior, creating a fitting image of the time, poised between the havoc of war and daily life.

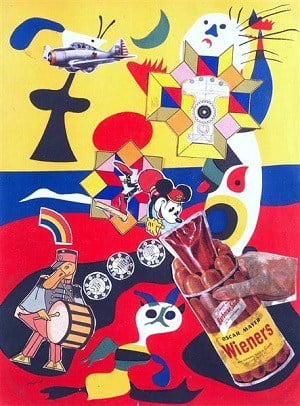

The greatest critical success of This is tomorrow was, however, Fun House by Group 2 – namely Richard Hamilton, John McHale, and John Voelcker, with the contribution of painter Magda Cordell and her husband, Frank Cordell. Their multi-media installation consisted of a massive assemblage of American ephemera: large scale images taken by magazines, advertising, billboards, Hollywood stills, plus a three-dimensional model of a Guinness bottle, an endless reel of film about the Royal Navy Fleet at sea, all accompanied by a jukebox continuously playing the sound of pop music and the recording of a robotic voice.

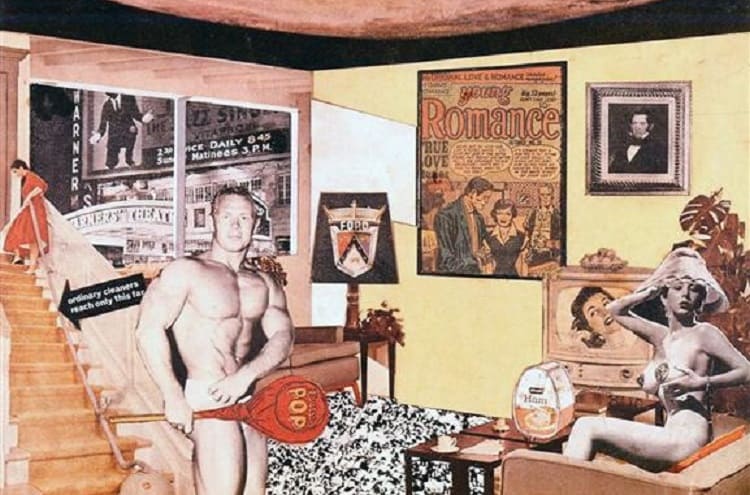

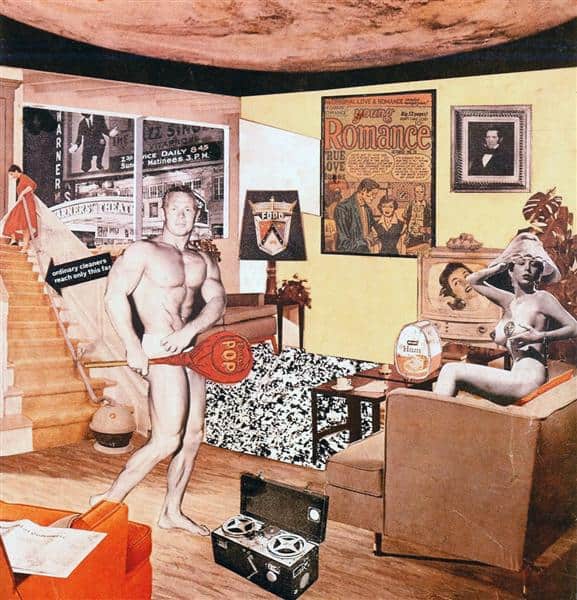

Even more iconic has become Hamilton’s collage designed for the cover of the catalogue, the celebrated Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?

Fragments of American magazines depict an interior domestic space populated by products emblematic of the modern era, from a large canned ham to new domestic technical appliances; but also a bodybuilder and a model, as contemporary Adam and Eva surrounded by new temptations. The collage, considered as the first genuine work of Pop Art, shows all the qualities that Hamilton himself would list the following year as distinctive of the genre: “Pop Art is: Popular (designed for a mass audience), Transient (short-term solution), Expendable (easily forgotten), Low cost, Mass produced, Young (aimed at youth), Witty, Sexy, Gimmicky, Glamorous, Big business”.

The legacy of This is Tomorrow

While bringing the Independent Group to wider attention, This is Tomorrow simultaneously turned out to be the collective’s swansong, as the group would never formally meet again. Their ideas, however, had a profound impact that can still be perceived to this day. Through the show, they provided a seminal model of collaborative art practice aimed at the integration of art and life, but, above all, they launched Pop art in a less-known yet formidable variation, playful and ironic, so distinctive from its American counterpart.

This is Tomorrow has never been replicated in its entirety, although individual installations as Patio & Pavilion and Fun House have been reproduced in different contexts, respectively on the occasion of Nigel Henderson’s (2011) and Richard Hamilton’s retrospectives (2014). In 2010, the Whitechapel Gallery revisited the landmark event with an archival show, exhibiting promotional materials, photographs, correspondence, and other documentation to the public.

In the words of a review of the time, the show innovated “many of our ideas on building and decoration that are still a Victorian skeleton scantily dressed with second-hand Bauhaus garments. The intention of This Is Tomorrow, in spite of its prophetic ring, is to make us more aware of what we must do to-day in order to avoid the repetition of what has happened yesterday in Dessau or in Zurich. And in art, an intention is often historically and socially as valid as an achievement”.

Relevant sources to learn more

For previous editions of our “Shows That Made Contemporary Art History” series, see:

Nazi Censorship And The ‘Degenerate Art’ Exhibition of 1937

The International Surrealist Exhibition of 1938

The Ninth Street Show