Articles and Features

Female Iconoclasts: Marlene Dumas

By Shira Wolfe

“I could say – South Africa is my content and Holland is my form, but then, the images I deal with are familiar to almost everyone, everywhere. I deal with second-hand images and first-hand experiences.” – Marlene Dumas

In our “Female Iconoclasts” series, we feature some of the most radical women artists of our time; those who defied prevailing social and art conventions in order to pursue their passion and contribute their unique vision to society. South African artist Marlene Dumas is considered one of the most significant contemporary artists, whose intense, emotionally charged paintings address existentialist themes and political issues.

About Marlene Dumas

Marlene Dumas was born in 1953 in Cape Town, South Africa. She studied at an English-language university in the city, and it was there that the artist, who had grown up in a rural area with a family who owned a vineyard, started to learn a great deal not only about her own world, but also about the world beyond. It was 1972 and she had never before taken classes with people of colour besides her own, or spent time with people from different religious backgrounds. At university, she was introduced to avant-garde artists, poets, playwrights and thinkers such as Picasso, Pollock, Lichtenstein, Ginsburg, Bergman, Godard, Resnais, Jean Genet, Athol Fugard and Tennessee Williams. Even though she wasn’t sure she would have the power within herself to do it, she knew she wanted to be an avant-gardist herself. At the end of her degree, she won a bursary to study abroad in the Netherlands for two years. When she left South Africa, she was in a sense relieved: townships were burning, there was a great deal of censorship and the question of Apartheid was complicated to discuss yet impossible to ignore. In the Netherlands, she felt safe and was able to read all the books that had been banned in South Africa.

Marlene Dumas’s Early Works

Early on, Dumas worked in collage as well as paint. She often used newspaper clippings as inspiration or material for her works, and her fascination for these media fragments can be traced back to her life in South Africa, where information about the world came from newspapers and magazines – television was only introduced in South Africa in 1976, four years after Dumas left the country.

In her large-scale blueprint collage Love Versus Death (1980), which is considered one of the key pieces of her oeuvre, Dumas pinned press clippings (most of them from the year 1977) onto two bands of paper which she called “clue-strips,” on either side of a large paper filled with printed drawings in the centre. The “clue-strips” contain everything from love stories, grief and mourning to political deaths, themes which she continued to explore throughout her career.

Key Themes, Motifs and Approaches

Dumas works within a specific field of tension: her works begin with various source materials, ranging from imagery culled from current media stories to art historical references or even celebrities.

She often zooms in one of these chosen images, appropriating the key qualities and altering and embellishing them to form a new unique identity . She uses many different techniques, even within the same painting. Some parts seem to be rapidly sketched, while other parts of the canvas are stained or almost brushed out, and she tends to work with thinned-down paint and faded colours.

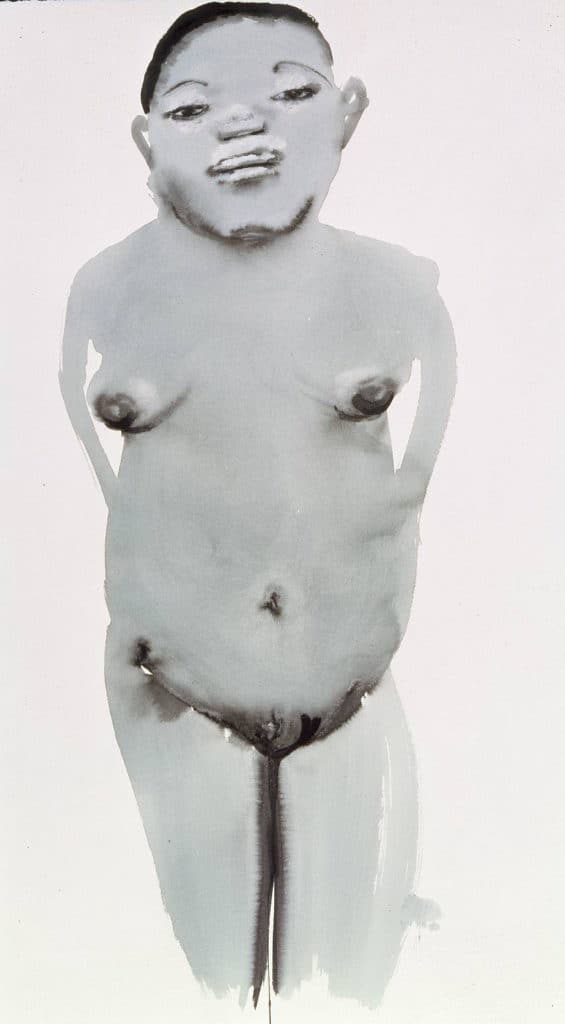

It is the human body and the existential human condition that has always formed the principal framework of Dumas’ work. Most of her body of work consists of disembodied heads or naked bodies, and her pieces without fail tackle the complex and intense spectrum of human emotions, without shying away from controversial topics. She once explained that she prefers to paint her subjects from photographs because it allows her the distance to paint with an “amoral” brush, thus giving herself the freedom to simply be immersed in the artistic process and detached from how others will consider her subject matter and message.

Portraits

Dumas’ portraits can be categorised into the following two groups: the living and the dead, and the anonymous and the famous. The commonality between all is that they tend to be painted in a gloomy, washed-out palette with the figure often seeming to float atop or above the surface of the canvas..

She keeps extensive folders filled with source material she’s gathered over the years, divided into different subjects. One of her first folders was simply titled “heads.” It’s an archive of images of all kinds of heads, faces, and portraits, but also of information. One article she collected describes the Mona Lisa’s smile, and on another page you might find a picture of Patti Smith, or Gertrude Stein’s portrait by Picasso.

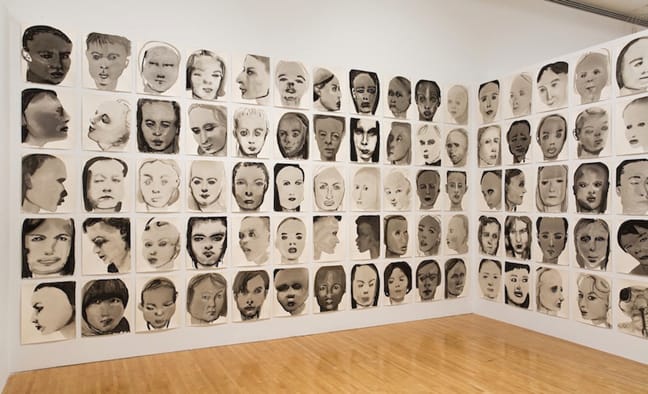

This is key to Dumas’ treatment of the human subject: she finds inspiration and relevance everywhere and places people on equal footing, no matter whether her subjects are friends, celebrities or criminals. In her 1994 Models, this is particularly evident as Dumas presented 100 different female faces in a gridded format, all executed with the same watercolour and ink wash palette on paper, and arrayed a visual essay of female diversity.

“Art is a way of sleeping with the enemy.” – Marlene Dumas

Political Works

Around 2000, Dumas started to make more overtly political works. She always remained drawn to the topics and political issues of her native South Africa, but also started turning her attention more towards representations of war on a global scale. She used images of dead terrorists, martyrs, combatants and other victims, reflecting particularly on the escalation of the interminable conflicts in the Middle East.

Dead Girl (2002) portrays a Palestinian girl who was shot and lies limp and bloody on the ground. Dumas said in an interview that she couldn’t get this photograph of the girl out of her head but thought she would never paint it, yet in the end, felt compelled to do so. She also thought she’d never in her life paint blood, but for this painting, she did. In 2010, she created some of her largest canvases yet for the series Against the Wall, which focused on the wall dividing Israel and Palestine. In one painting, she portrayed a group of Hasidic Jews standing in front of the separation wall, which in her rendering bears a great resemblance to the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem. In response to this piece, she said: “Well, Picasso had his Guernica. I’ve got something I want to express, and I must express it.”

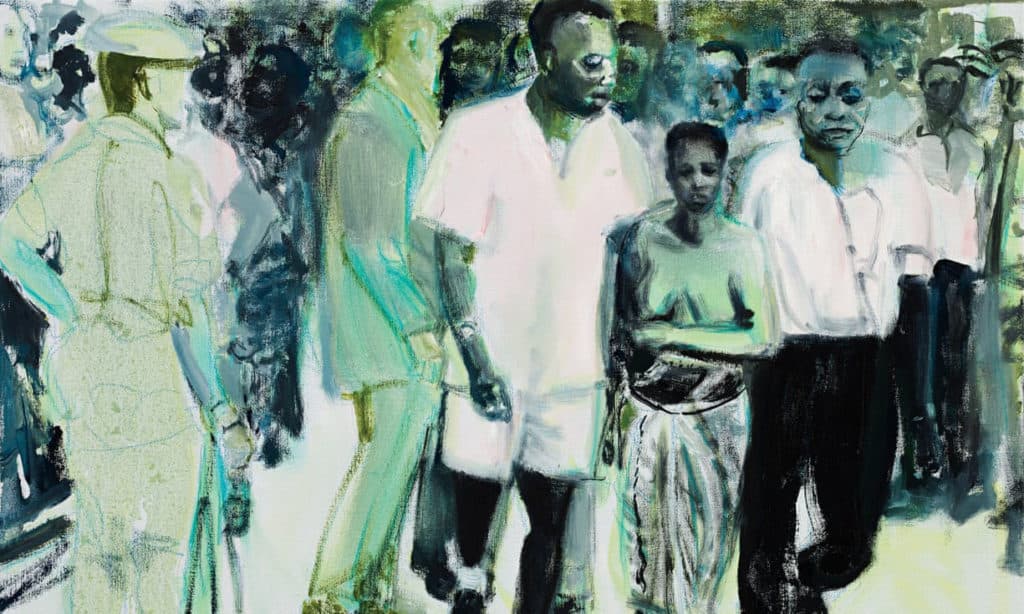

Another powerful image is The Widow (2013), which portrays Pauline Lumumba walking through the streets of Léopoldville mourning the death of her husband Patrice Lumumba, the former Prime Minister of Congo who was executed by Katangan forces in 1961.

Marlene Dumas: Continual Development

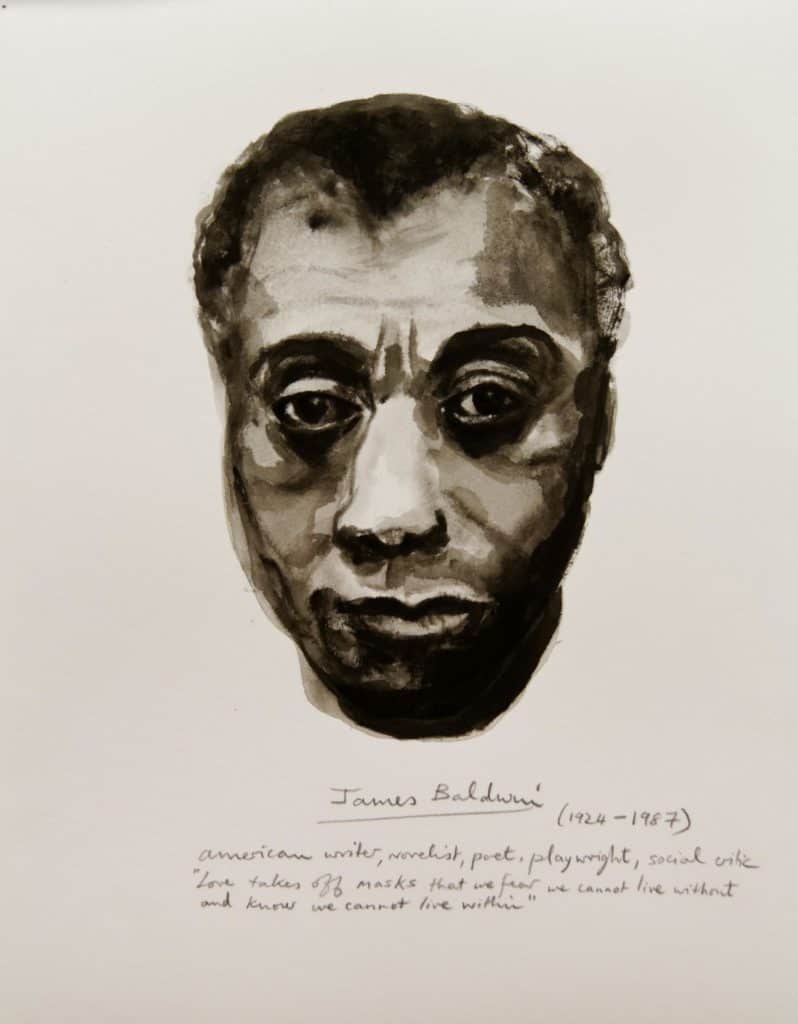

Dumas allows for her works to keep developing and evolving, also permitting the context they are exhibited in to exert an influence. For example, her Great Men portrait series, which consists of ink portraits of gay men throughout history, evolves according to where it is exhibited. Examples of some of her subjects are James Baldwin, Francis Bacon and W.H. Auden.

Dumas is widely regarded as one of the most influential painters working today. Over the past four decades, she has continuously probed the complexities of identity and representation in her work, and whilst they may be categorised largely as ‘portraits’, we have come to understand them as representing an emotion or a state of mind. Consequently, she has become one of the key figures in contemporary figuration’s attention to themes such as race and sexuality, guilt and innocence, violence and tenderness.

Relevant sources to learn more

For previous editions of our “Female Iconoclasts” series, see:

Female Iconoclasts: Zaha Hadid

Female Iconoclasts: Georgia O’Keeffe