Articles and Features

Cameraless:

Adventures In Photography With No Camera

By Adam Hencz

Photography and the creation of photographic images are conventionally associated with the application of a camera or device that captures various visible and unseen realities. Cameraless techniques have been unduly sidelined by conventional histories of photography ensuring that narratives about the craftskill of the darkroom and its associated chemistries have been underappreciated, or even neglected completely.

Artists working with the most elemental kinds of photography have throughout the history of the medium been untethered from the dictates of the black box, metaphorically stepping in to replace the camera and creating photographic images using just light-sensitive paper or film, emulsion and a source of light or radiation. At the advent of photography only small circles of scientists used cameraless photography and almost exclusively to illustrate plants and biological specimens, deploying the new medium for scientific and documentary purposes rather than artistic ones. It was with the advent of modernism, particularly the constructivists and dadaists that recalled and reinvented these rudimentary methods, expanding the medium with new materials, abstract depictions and the element of chance.

The cameraless image is direct, without any intermediary stage. Nature gets to represent itself without minimal mediation by the human hand and the use and manipulation of an apparatus is secondary to the process itself. The selection below is by no means exhaustive, but illustrates a lineage of the practice as exemplified by the widely diverse contexts and motivations of the medium’s pioneers.

William Henry Fox Talbot

At the advent of photography, inventors experimented with photographic processes purely for scientific reasons. Among the very first was William Henry Fox Talbot who discovered and created light sensitive material as early as the 1830s. He was a true polymath; his curiosity embraced subjects as varied as mathematics and botany, philosophy and philology, astronomy and art history. After graduating from Trinity College in 1834 he returned to his monastic Lacock Abbey home where he began to experiment with fine writing paper and silver nitrate to make precise tracings of botanical specimens. He would collect plants and leaves, place them on a photosensitive paper, cover it with a sheet of glass and set it for a couple of hours in the sunshine.

One of his early experiments was an image that later came to be called A Cascade of Spruce Needles. Talbot scattered some pine needles across his horizontal sheet of prepared paper. The uncovered fragment of the paper would change color and darken, bringing various shades of brown alive. The result was a reversal of tones around and along the edges of the forms themselves, a kind of negative on paper. With this process he created contact prints that he later called photogenic drawings. At first, Talbot was not able to stop the photosynthetic process and fix these images, so they were to be seen very carefully, and only by candle-light. The same natural phenomena that created these images would have destroyed them in broad daylight.

Image courtesy of The British Library.

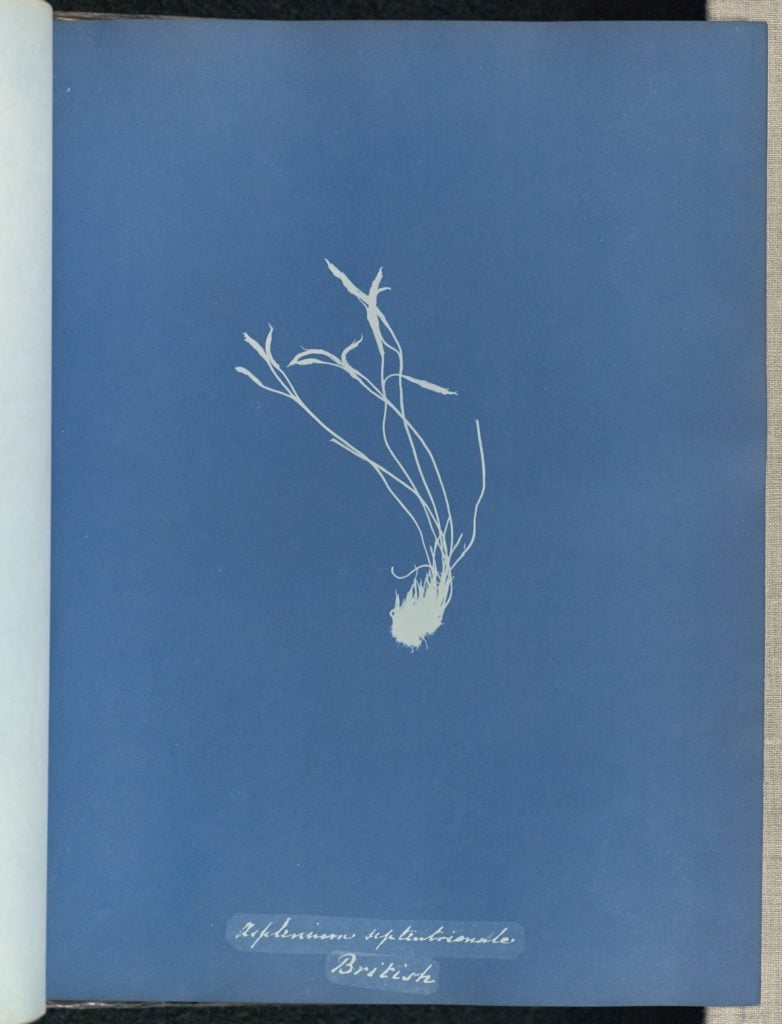

Anna Atkins

As the first person to publish a book illustrated by light-sensitive materials and possibly the first woman to ever create a photograph, Anna Atkins has contributed enormously not only to the documentation and understanding of plant life in Britain but also to the history of photography itself.

Raised by her father, she developed a passion for botany at an early age and later learned about photography first hand from its contemporary pioneers. She correspondended with Fox Talbot himself and was good friends with Sir John Herschel, who discovered the cyanotype process in 1842. Herschel taught Atkins about this new, non-silver type process that produced a blue and white image derived from the salts of iron. Before the invention of photographic processes, scientists relied on drawn and painted illustrations, but cyanotypes enabled Atkins to record plants and natural specimens in incredible detail. Her delicate compositions merged science and art. She was not working alone – with the assistance of Anne Dixon they transformed the way botanists could work. Atkins is also accredited with the creation of the first photographically illustrated publication, British Algae in 1843 and by doing so established photography as an accurate medium for scientific illustration.

Cyanotype printing was exclusively taken up by a small circle of botanists at first and did not see wider use until the end of the 19th century when it started to appear in engineering applications and architectural blueprints. The cyanotype has later also become widely used among photographers as a proofing material for making contact prints.

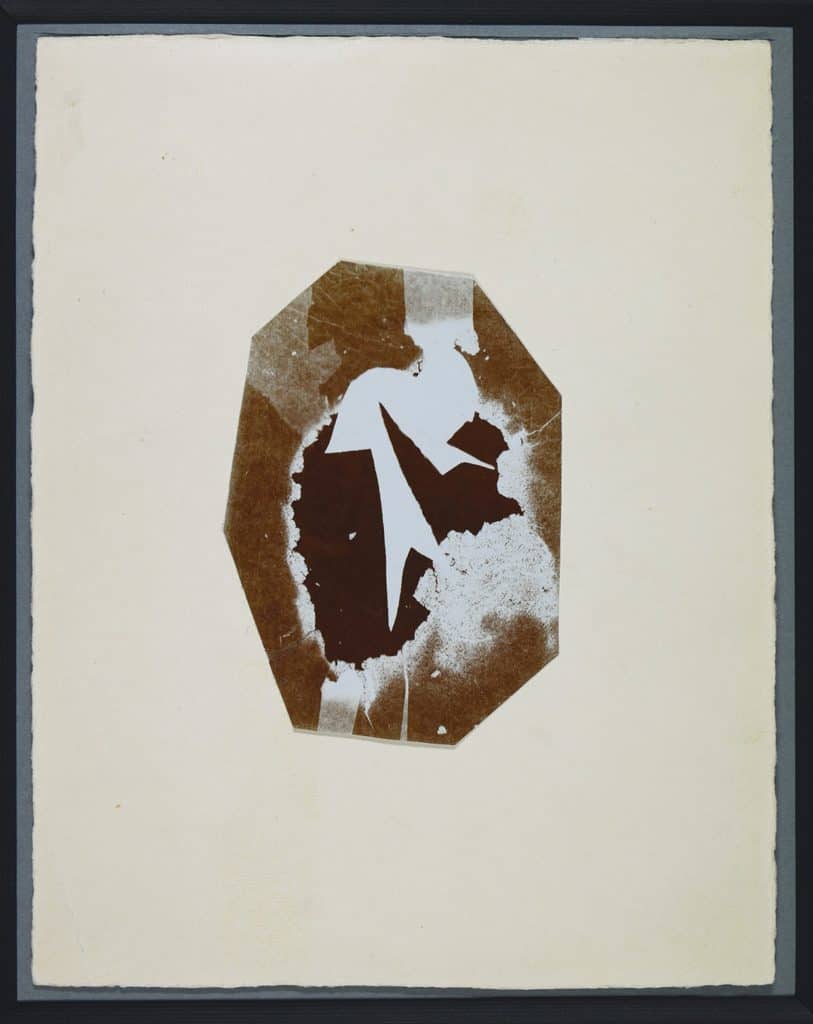

Christian Schad

The German dadaist, Christian Schad was the first one to intentionally use photographic processes for purely abstract artistic purposes. He started experimenting with light sensitive materials in 1918 in Geneva, Switzerland, during the visit of a friend. Reminiscing about childhood memories, playing with light and casting shadows, Schad began to push the boundaries of the medium and liberated by the mission of the dada movement, he turned away from the urge of representation and the camera-based standards of photography. Schad selected particularly worn materials, such as scraps of paper and bits of fabric, creating photograms with existing photographic techniques. The dada theorist Tristan Tzara later acquired some of his early works and dubbed the method schadograph as a play both on the creator’s name and the omnipresence of shadow within his process.

Among Schad’s avant-garde contemporaries who rediscovered and advocated for the photogram was Man Ray. In 1921, a few years after the appearance of schadographs, Ray arrived in Paris from New York and soon embraced the photogram technique. Ray’s approach was technical and aimed to explore and combine all photographic tools at his disposal. He’d place three dimensional, often almost see-through objects as the subject of his photograms, uniquely showing their texture. To popularize his technique, he called his distinctive works rayographs.

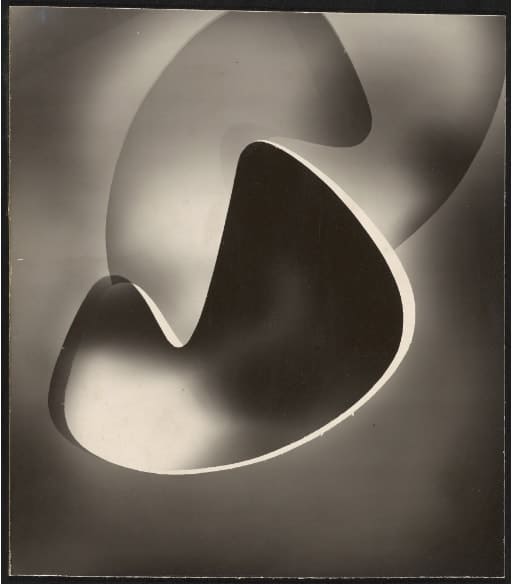

László Moholy-Nagy

Moholy-Nagy was a member of the Hungarian avant-garde, experimenting with painting on unconventional materials, such as aluminum, plastic and formica in his early years. In 1919 he left Budapest for Vienna and proceeded to Berlin where he met Walter Gropius, the principle of the newly opened Bauhaus who appointed him as its youngest professor. He arrived in the midst of a key change, when the school was moving towards integrating technology and industry into the arts.

His experiments with photograms started in his Berlin studio in 1922. His years at the Weimar Bauhaus revolved chiefly around photography. He was fascinated by transparency and light and particularly interested in the idea of painting with light, displaying translucency and ambiguity of form, and also movement on light-sensitive photographic paper. The dynamic photograms that he achieved with these experiments have become known as luminograms. Moholy-Nagy worked with different media throughout his relentlessly experimental career and his ideas influenced the practice and attitude of fine art, photography, typography, stage design, and design education.

27.3 × 24 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Pierre Cordier

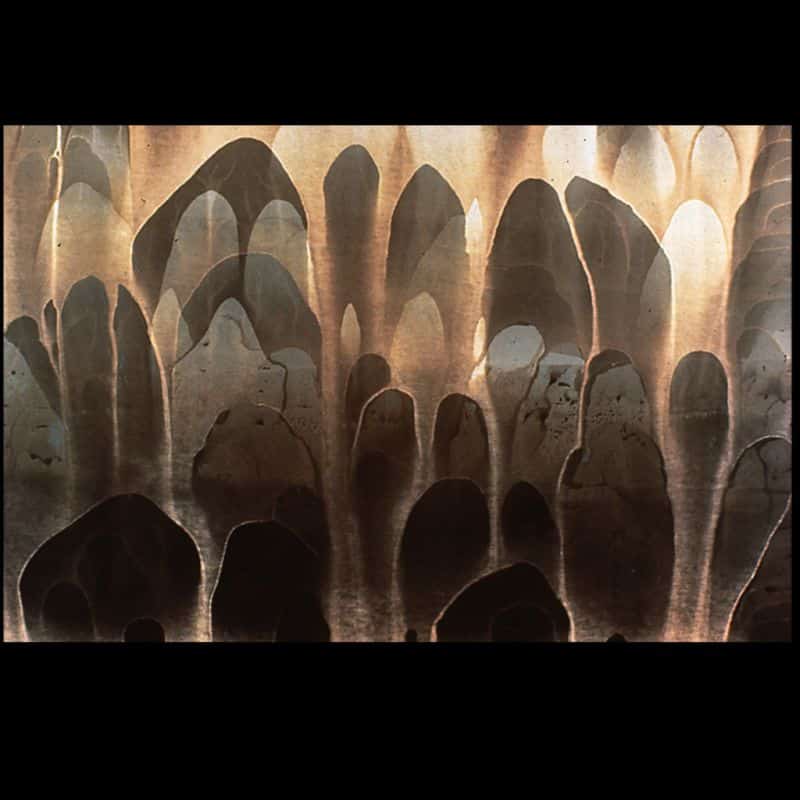

Pierre Cordier is a Belgian artist who was among the first artists to cultivate the element of chance and invite it as a collaborator in his artistic practice. There was little talk about aleatory or random art when Cordier began experimenting and modifying existing photochemical processes. He works on the very edge of control, incorporating the results of chance into his artistic goals.

Cordier was born into an industrialist family specializing in cosmetic products, especially nail polish. In 1956, during his military service in Germany, near Cologne he wrote his dedication to a young girl, Erika, putting brush strokes of nail polish on light sensitive paper, then dipped into the developer. This became the first piece of his unique method that he later called and patented as chemigram. The chemigram combines the physics of painting (varnish, oil, wax) with the chemistry of photography (photosensitive emulsion, developer, and fixer), without the use of a camera, enlarger or darkroom, and in broad daylight. The technique is para-photographic, it is more related to engraving, painting, or lithography, than to photography itself. He was already interested in painting (Max Ernst, Paul Klee, Gustav Klimt, Saul Steinberg) and in photography (Fox Talbot, Hippolyte Bayard, Man Ray, Moholy-Nagy) at the time he invented the chemigram.

He keeps on experimenting, pushing the limits of the photographic medium as of today and has been producing chemigrams as his principal medium since then. More recently, Cordier’s work has been exhibited at the Centre Georges Pompidou and the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Courtesy of the artist.

Courtesy of the artist.

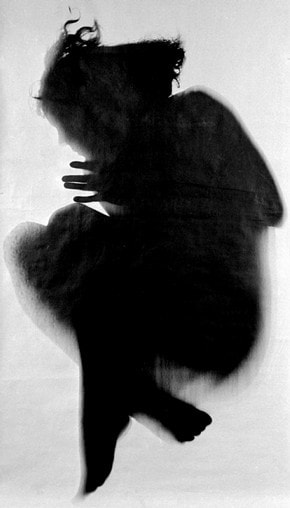

Floris Neusüss

Neusüss is particularly known for his unique cameraless techniques, large-scale, figurative photograms and his contribution to the special development of the medium. In the 1960s Neusüss developed intimate, full-body photograms as he exposed naked figures onto photographic paper he dubbed as Körperfotogram (nudogramm). As the paper was pulled through the development process, a white silhouette of a female figure on a black background became visible. Neusüss was particularly interested in this process as it presents his subject’s reverse side to be recorded. Their shadow becomes visible and permanently printed.

Born in 1937 in Lennep, Germany, Floris Neusüss studied at the art school in Wuppertal and at the Bavarian Stately School for photography in Munich. He graduated in 1960 at the Academy of Fine Arts in Berlin. From 1971 he was a Professor in Experimental Photography at the University of Kassel. Neusüss dedicated his whole career to exploring the photogram and stretching the boundaries of the medium. He recently passed away in April 2020. He is represented by Von Lintel Gallery alongside London’s Atlas Gallery. Today, his works are held in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Getty Museum in Los Angeles and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, among others.

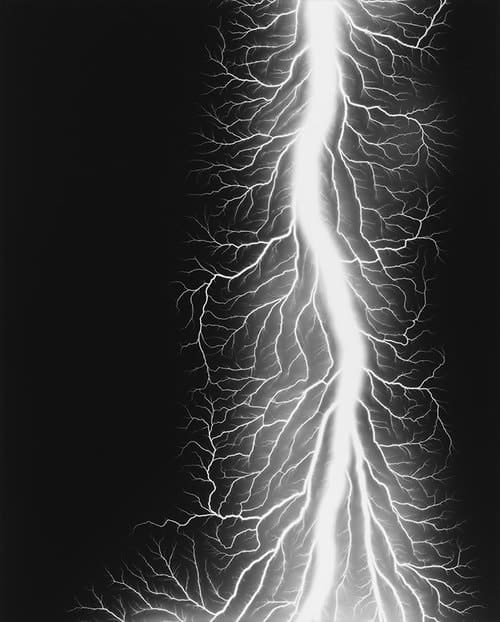

Hiroshi Sugimoto

During his career, Hiroshi Sugimoto has developed his work around ongoing photography series started in the late seventies such as the Dioramas along with the Seascapes and Theaters series. Sugimoto’s artistic approach explores the notions of memory and time notably through long exposure photography. In one of his cameraless series he explores electricity, an element that has historically been problematic and uncontrollable for photographers as it scars film and destroys images.

Sugimoto created his images by zapping 400,000 volts supplied by a Van de Graaff generator onto films. His final prints are enlargements from a selected portion of his negatives and depicts dramatic effects of electricity. Sugimoto’s current series continues the exploration and documentation of traces of invisible but elemental forces. Optics is currently on view at Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco until 15 August. Works by Sugimoto reside in major collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and the V&A Collection, London.

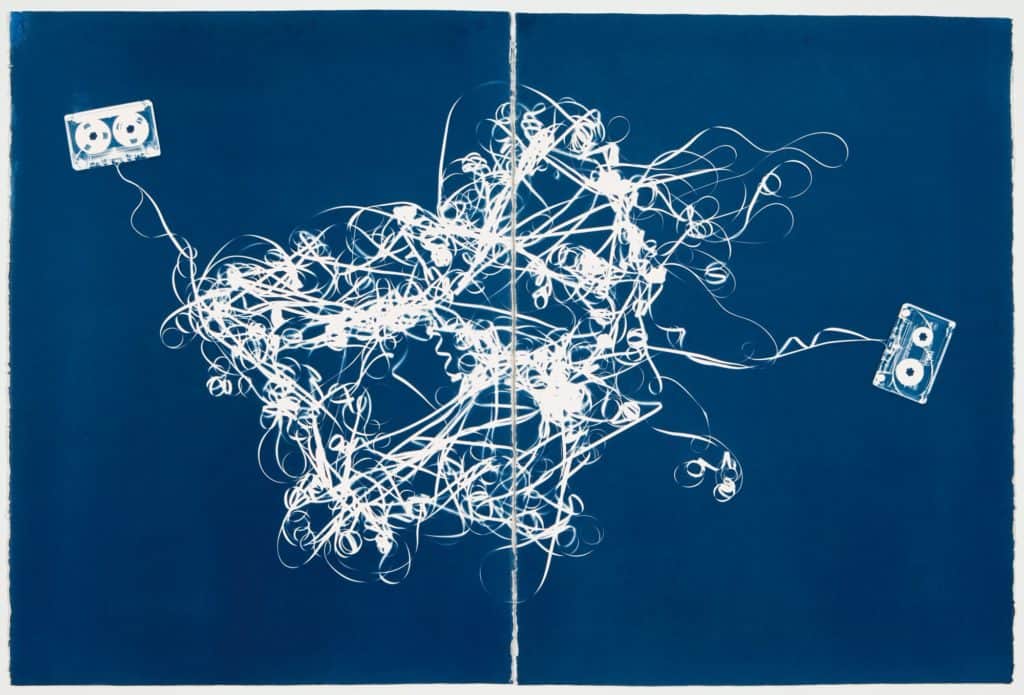

Christian Marclay

Christian Marclay is a New York-based visual artist who explores the juxtaposition of sound, photography, film and video in his works. Best known for his turntable collages and 24-hour film The Clock, in his two-year collaboration with traditional printmaking studio (Graphicstudio), the artist revisits the early days of cyanotypes. His specimens were cassette tapes. He collected hundreds of cassettes from Tampa thrift stores and layered them into various compositions. Together with Graphicstudio, Marclay was testing the different combinations of emulsion formula, and cold-press watercolor papers to find the perfect Prussian blue color reminiscent of the first cyanotypes. He used multiple exposures of high-power ultraviolet exposure lamps and ultimately created six distinct series of cyanotypes, the largest more than eight feet long.

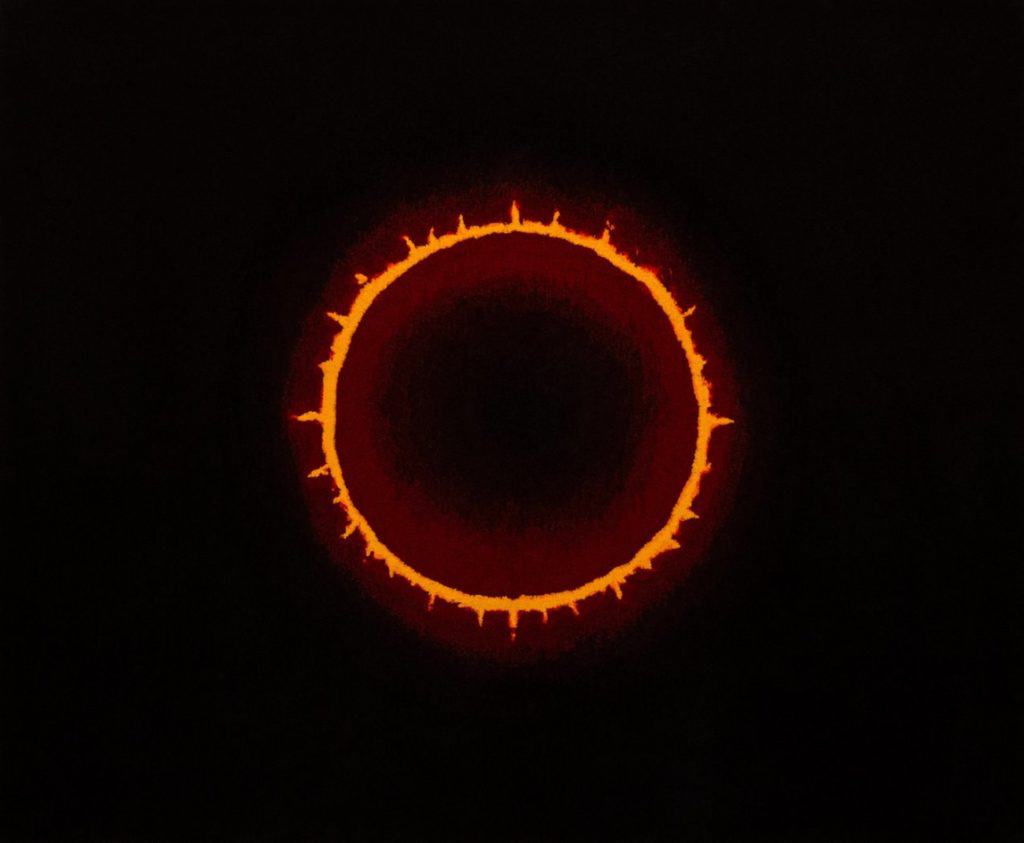

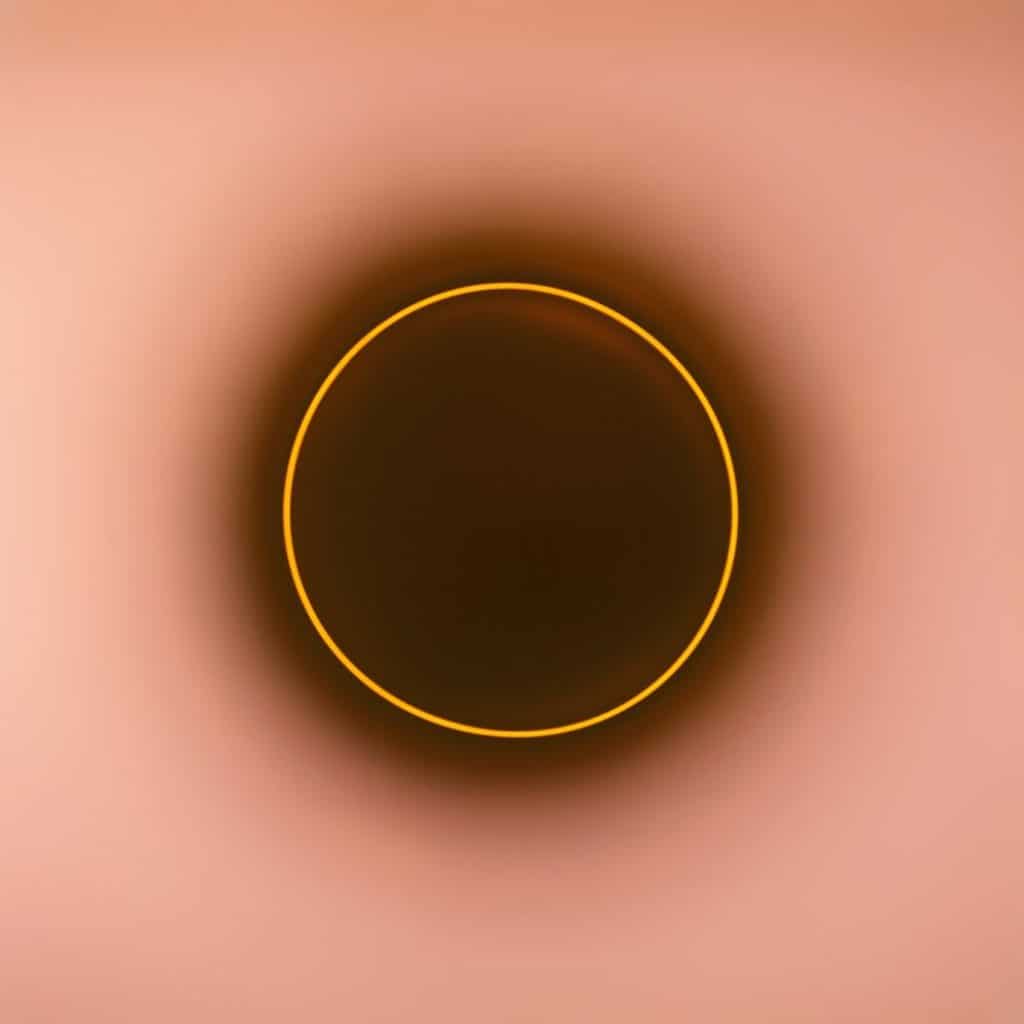

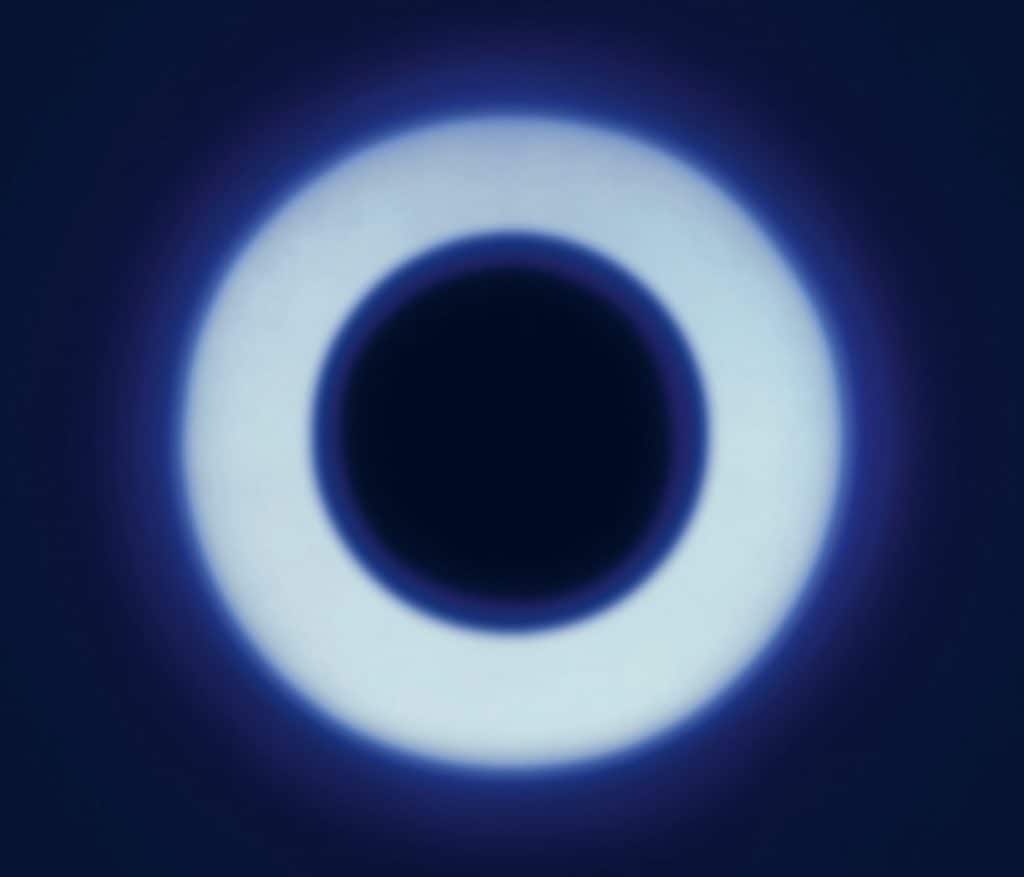

Garry Fabian Miller

In the midst of his successful landscape photography career, Garry Fabian Miller turned his back on the camera and dedicated his work to the craftsmanship of the darkroom. He creates cosmic shapes exploring elements of time, light and color with a beam of light and photographic paper. He lets the Sun shine through transparent objects, colored glass vessels and over cut-paper shapes leaving photo paper underneath to be exposed from minutes to sometimes hours, then developed to be studied in his light-flooded studio. The use of dye destruction print paper allows him to create transitory spaces in his composition, where colors meet, forms entangle and fade into each other. The merging of edges and themes of disappearance and emergence are central to his work. His latest body of work, Midwinter Blaze was on view at London’s Ingleby Gallery.

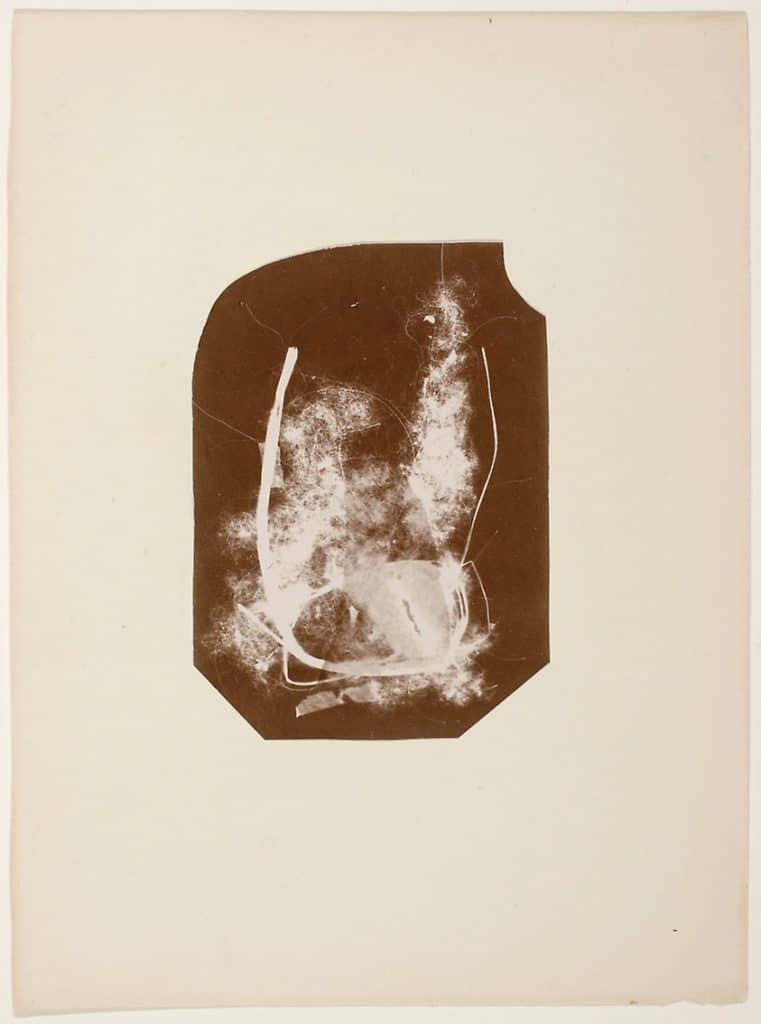

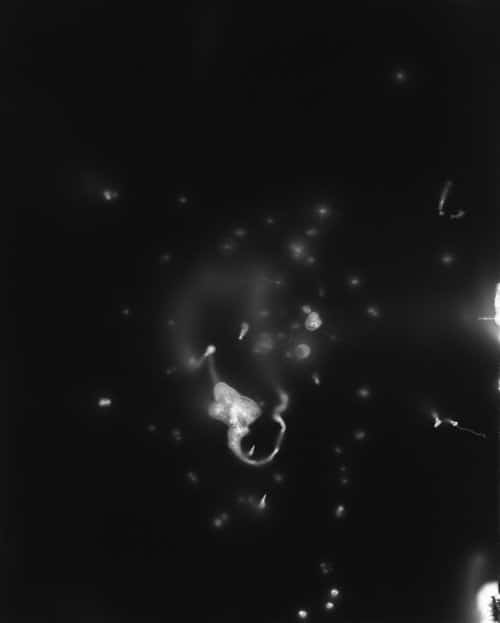

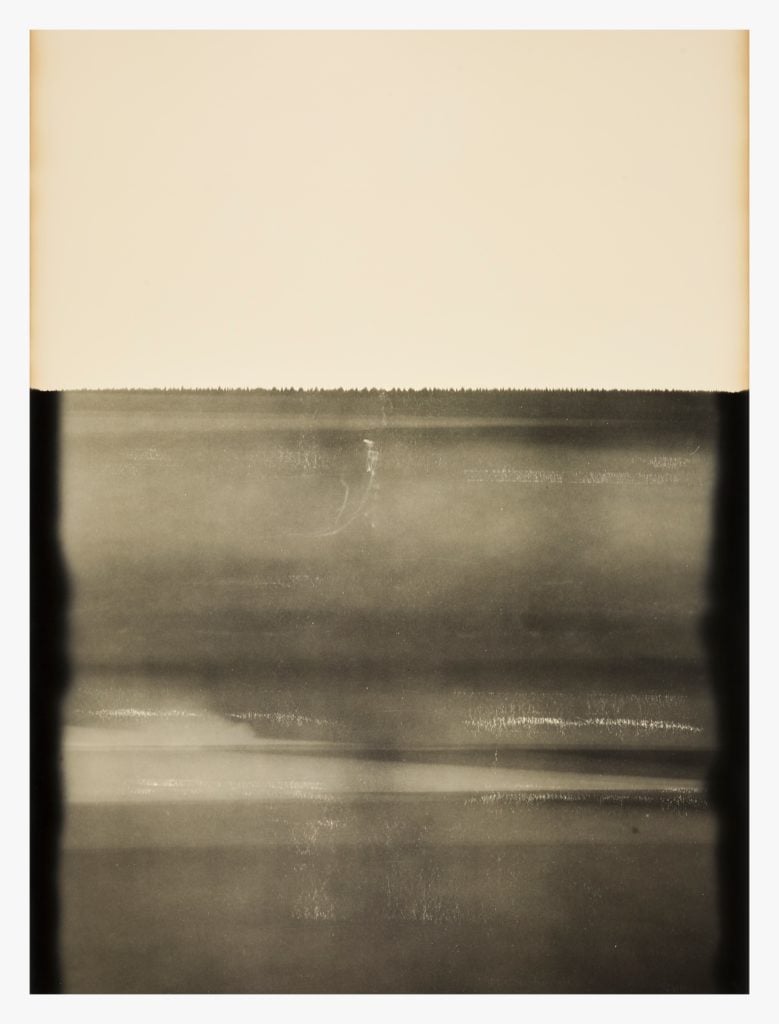

Alison Rossiter

Allison Rositer has been collecting expired photographic paper from every decade of the 20th century for several years now since she started to search for them on eBay. She processes them in the darkroom, simply taking them out of the bygone packaging she finds them in, developing them with standard black and white chemistry in the darkroom.

Her work makes latent images that are made by degradation, atmospheric damage, light leak, mold, or even fingerprints of the previous photographer visible. These images encompass decades, in some cases more than a century. During this vast time frame silver tarnishes, mold blooms and depicts dark landscapes that otherwise would take years to develop naturally and intentionally. Producing imagery with expired paper offers different avenues and the open ended exploration of darkroom techniques.

Expiration dates on the paper packages are repurposed in Rossiter’s works and they point to the history of photography that is behind us and she is offering a way to see it. “[It is a] way of sampling earlier time frames in the history of photography, by giving them a new purpose now by finding them again.”

Yosi Milo Gallery, New York.

Yosi Milo Gallery, New York.

2010, gelatin silver print, 21.6 × 16.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Relevant sources to learn more

The latent image and camera obscura

How to Make a Photogram (checklist), MoMA exhibition