Articles & Features

A Short History Of the African Diaspora Through the Eyes of Its Visual Artists

By Naomi Martin

“They dragged you from homeland, They chained you in coffles, They huddled you spoon-fashion in filthy hatches, They sold you to give a few gentlemen ease.”

Sterling Brown – Extract from Strong Men

The Artistic Legacy of the African Diaspora

Throughout history, Black visual artists have depicted the brutality and magnitude of the African diaspora – the forced migration of bodies, identities and culture from the African continent, mainly due to the transatlantic slave trade. The artistic and aesthetic approaches to the African diaspora have predominantly revolved around a critique of colonialism and its legacies, while celebrating the development of Black culture across the world. The duality of this diasporic selfhood has led Black artists to enter a state of permanent hybridity, a constant oscillation between cultures, places and identities, vividly expressed through their art.

In the wake of unceasing racial violence, attention has been brought to Black visual artists like never before – but while the power and support they have attained might seem like a breakthrough now, the primacy and message of their art are in fact, centuries old. The struggle for African American artists has always been the same – to grasp control of their culture and endeavour to showcase it to the world in all of its complexity and diversity. Beginning in the late 19th century, and moving through the subsequent hundred and fifty years, we take a look at some of the most powerful and multifaceted African American artists, powerfully depicting issues of racial oppression and identity.

The Pioneering Figures

Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Monet, Van Gogh, Picasso, Dalí, Warhol – these are but a few of the names that most often come to mind when thinking about art history. Although they undeniably are remarkable artists, they also share two distinctive features, whiteness and maleness. As a black woman in late 19th century America, Edmonia Lewis was not favoured by conditions conducive to her success, yet her talent and perseverance allowed her to become the first professional sculptor of African descent, and her name deserves to be celebrated to the same degree as the likes of Rodin or Bernini.

Lewis was of mixed African and Native American descent, and had to overcome a succession of unmatched obstacles – victim of daily discrimination, accused of stealing and poisoning her schoolmates, expelled from College, beaten and kidnapped, she nonetheless managed to rise up and become an important practitioner of the Neoclassical style. Little is known of the details of her personal life and journey, and while it is believed that a great part of her work did not survive, some extremely compelling sculptures did, such as The Death of Cleopatra, depicting the empowerment of a woman dramatically determining her own fate in death.

Like Lewis, Henry Ossawa Tanner was among the few African American artists able to gain access to artistic training throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Although he lived most of his life in France, Tanner was born in Pittsburgh. His father was a minister and his mother a slave who had escaped north through the Underground Railroad. Most of his earlier works were rather spiritual, fragments of his religious upbringing, but after moving to Paris that Tanner achieved two of his most emblematic paintings, The Banjo Lesson and The Thankful Poor. Haunted by the psychological and cultural legacy of slavery, Tanner endeavoured to gracefully depict African American subjects, fighting the stereotypes of the “Uncle Tom” figure. With The Banjo Lesson, Tanner depicted one of the most meaningful instruments of the slavery era to immortalize a noble and intimate interaction, adroitly emblematizing the shared journey of the African diaspora.

The Harlem Renaissance

Between the First and Second World War, the Harlem Renaissance was thriving, carving a new and prominent niche for African American culture within the rapidly expanding cultural hegemony of American culture as a whole. The movement was a significant milestone in allowing people of colour to exercise control over their identity and celebrate black culture through both social consciousness and activism, while battling racial labels and stereotypes. Among the most preeminent visual artists to contribute to the Harlem Renaissance was Charles Alston – first African American artist to be allowed to teach at the Arts Students League, and to be appointed by the Art Commission of New York City.

Alston started out by drawing political and satirical cartoons while studying at Columbia University, highlighting the dynamics of race relationships. Because of his race, he was not allowed to participate in life drawing classes. Instead, he went on to establish the Harlem Art Workshop and the Utopia House program for the aspiring artists of Harlem youth. Throughout his career, Alston was devoted to promoting and empowering African American culture, and to exploring and reclaiming racial identity. Inspired by the likes of Picasso and Modigliani, as well as African art archetypes, Alston sought to address the different aspects of the Black experience and its attempt to blossom in a white-dominated world, as well as share his artistic knowledge and endeavours by mentoring younger artists – including Jacob Lawrence.

Guided and tutored by key figures of the early Harlem Renaissance such as Alston and Augusta Savage, Lawrence’s work always strove to express the African American experience especially in the context of the African diaspora. The Migration Series is where his storytelling skills can be most vibrantly grasped, simultaneously conveying metaphors of beauty and injustice. The series consists of 60 panels of the same size, each accompanied by a caption, reminiscent of a film storyboard narrating the Great Migration. A tale of hope and disappointment, The Migration Series is one of Lawrence’s most stunning achievements, still resonating today in its poignancy.

The Cultural Climate of the 1970s

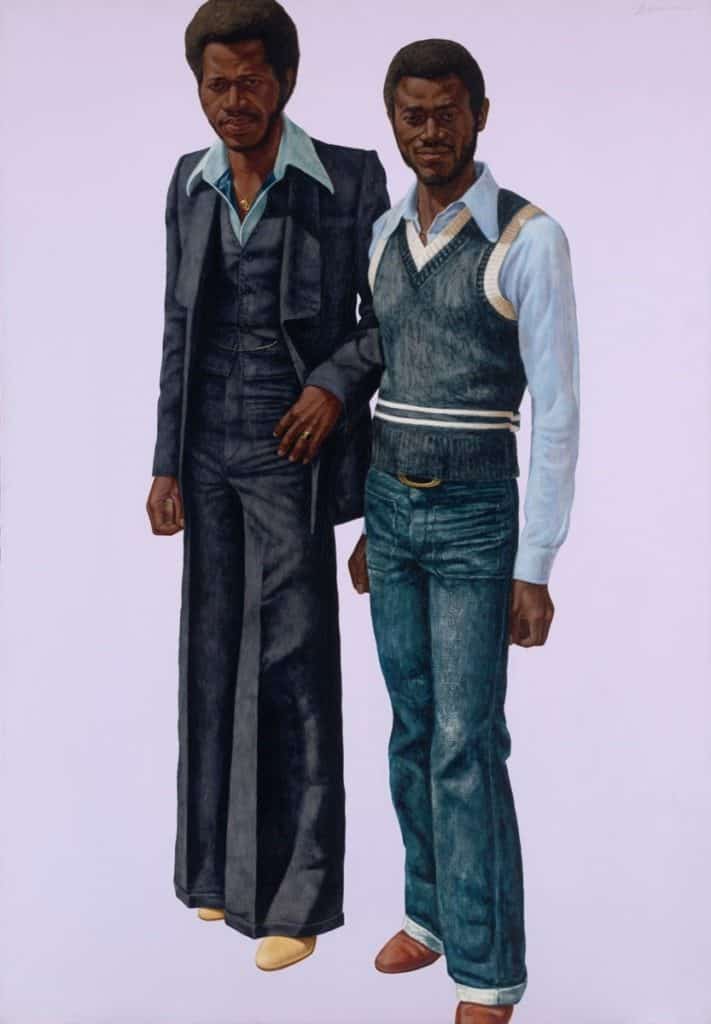

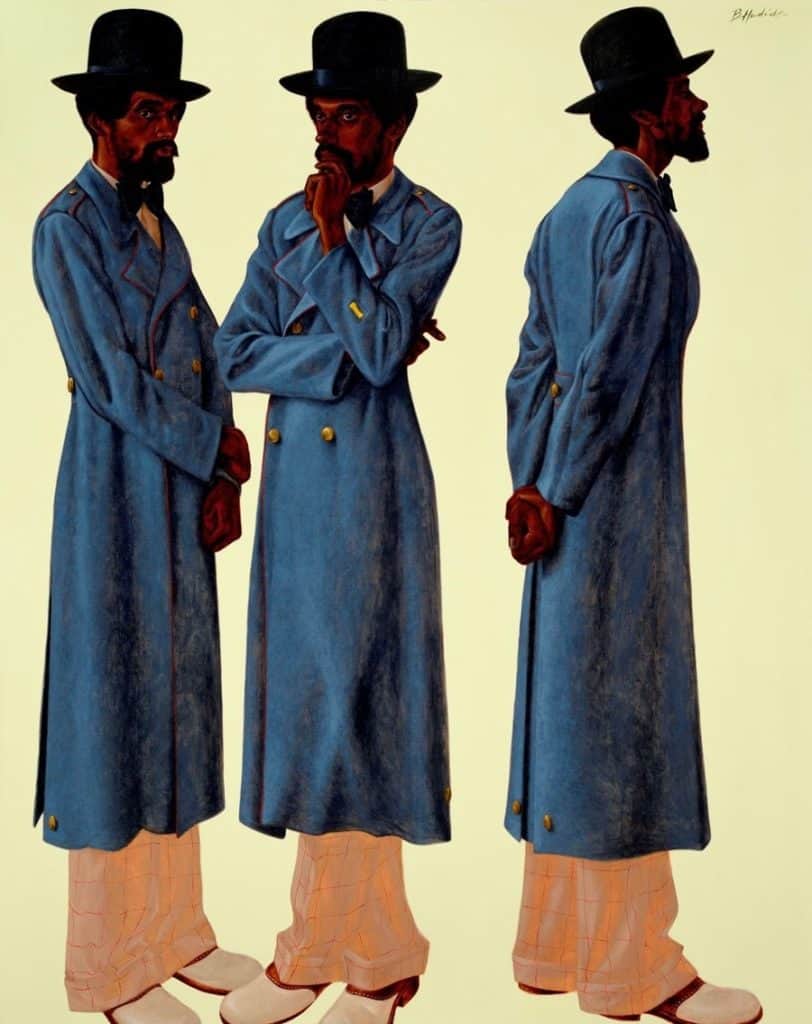

Following the legacy of the Harlem Renaissance and the civil rights victories of the 1960s, the 1970s saw a further renewal in African American art, fuelling the idea that black visual artists ought to keep exploring fundamental questions of identity and representation of the Black community through their creative endeavours. Some of the most influential figures to have marked the 1970s with their narration of the legacy brought upon by the African diaspora include Barkley L. Hendricks, Faith Ringgold, and Ming Smith, amongst others. Hendricks was a pioneer of Black portraiture – astounded by the lack of Black representation in Old Masters’ paintings, he decided to coalesce art history with queries of cultural heritage, capturing the raw emotions and stylish personalities of his entourage in classical, Baroque-like portraits. With a vibrant and precise sensitivity, Hendricks strived to free his community from the burden of a white-centred outlook on art.

“I can’t tell your story, I can only tell mine. I can’t be you, I can only be me.”

Faith Ringgold

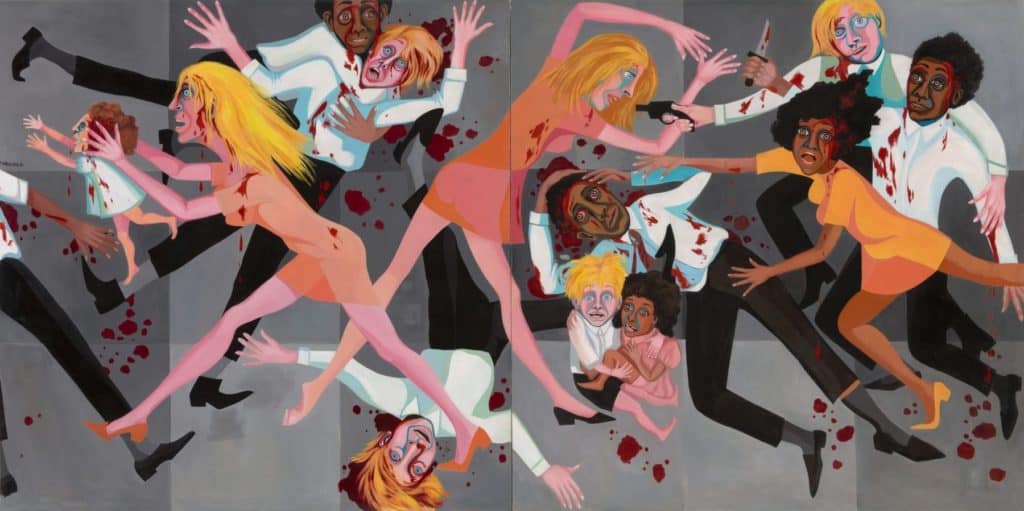

Faith Ringgold is another significant artist whose political oeuvre flourished during the 1970s. In 1967, her American People Series gained critical attention, particularly with Die, which brutally depicts race riots in a tangle of blood and bodies. When painting this piece, Ringgold explained that she was documenting what was happening around her in the African American community. Throughout the 70s Ringgold experimented with various mediums, including silk painting and quilt work, a genre for which she is best known today. Quilts were an art form used by slaves, which Ringgold chose to appropriate in order to denounce discrimination and rewrite African American history, reviving the buried voices of the past in the hope of strengthening the future of the Black experience.

Silkscreen. Image courtesy of the artist.

From the 1980s Onwards

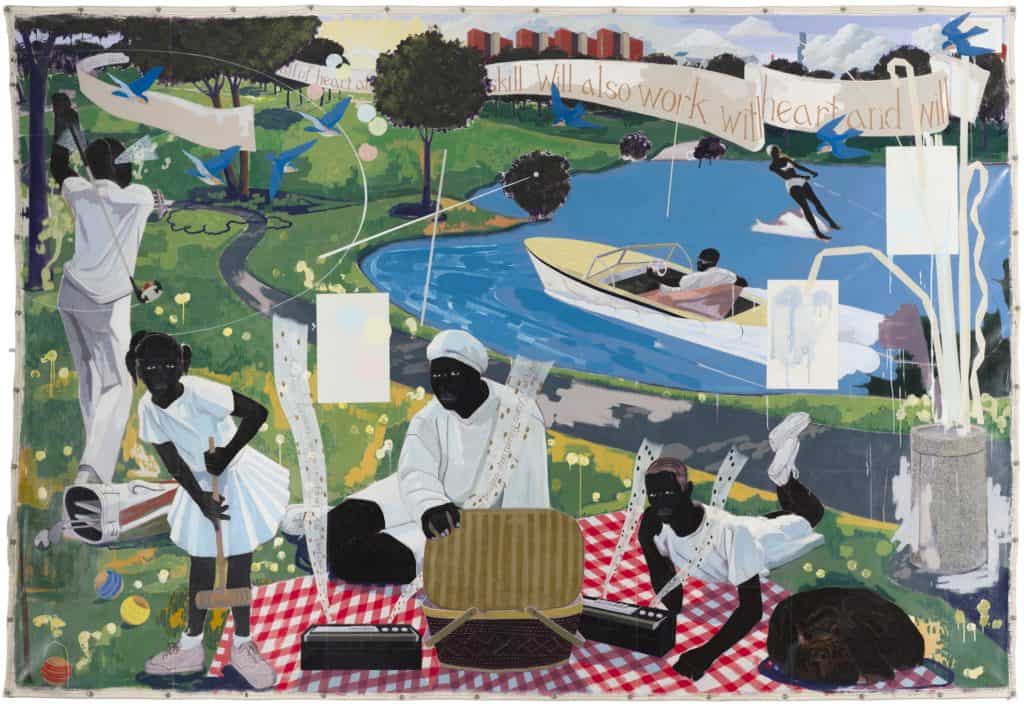

Few artists epitomized the 1980s New York art scene like Jean-Michel Basquiat, with his characteristic stream-of-consciousness graffiti style. Although he lived a short life, Basquiat was a prolific artist, forever intertwining issues of race and identity through his work. Even at the peak of his fame as one of the greatest art world darlings of the late twentieth century, Basquiat was still both a victim of and witness to racism. After the death of Michael Stewart – a young graffiti artist – at the hand of two police officers, he painted one of his most personal and political works, Defacement; a visceral response to the ceaseless oppression experienced by the Black community. The marginalization of the African American community is also at the core of Kerry James Marshall’s oeuvre, who bases most of his work on art-historical references, attempting to rewrite the past by placing blackness at the centre. Marshall aims to battle the never-ending stereotypical representation of black figures in art and the popular media, by devoting himself to creating rigorous paintings celebrating the beauty, complexity and richness of a non-negotiable blackness.

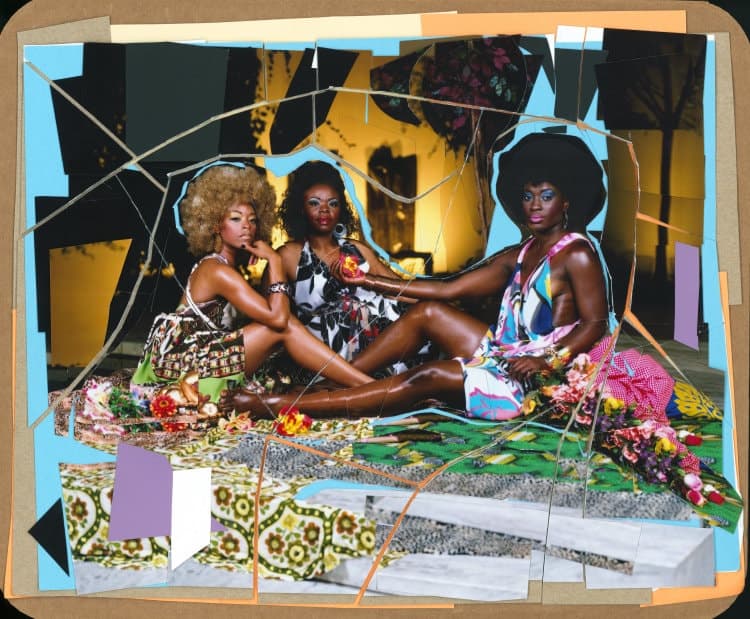

Throughout time, these artists poured their talent and vision into celebrating the legacy of the African diaspora, a collective voice running through the early modern and twentieth century periods and uniting the Black community in narrating tales of injustice, violence and hope. Kara Walker and Mickalene Thomas are two significant contemporary artists who have also contributed to re-telling the story of the African American Community. Thomas’ work focuses on honouring and analysing the intricacies of the Black female identity, while Walker is renowned for her striking black and white silhouette cut-outs dealing with themes of racial identity. Walker’s collages materialize somewhere between violence and humour, enticing viewers into a critical narrative exposing the scenes of an untold Black history.

Another artist combining political and aesthetic statements, David Hammons is among the most influential figures confronting cultural stereotypes, using in his work elements seemingly inherent to the African American culture, such as dreadlock clipping and basketball hoops. Since the 1960s, Hammons experimented with various mediums and strategies, attempting to speak about the fragility of the African American cultural representation. With Higher Goals, in 1986, Hammons denounced basketball as an issue for the Black community, preventing the younger generation from getting educated and considered beyond athletic capabilities. Almost 15 years later, he came back to the game and its implications of discrimination and elitism, with his intricate baroque-like basketball hoops sculptures.

Reminiscent of Barkley L. Hendricks’ work in the 1970s, Kehinde Wiley is another eminent artist who chose to celebrate blackness through portraiture. Wiley is renowned for his seamless blending of art history and present-day street culture, juxtaposing Old Masters’ paintings with modern elements and placing – often young – Black subjects at the centre. Wiley is among the most influential Black contemporary artists challenging notions of racial identity, and gained tremendous global recognition after being commissioned to paint Barack Obama’s portrait. Another who co-opts the tropes of grand history painting in order to convey a new narrative for blackness is Titus Kaphar, an artist whose brilliant canvases flip the script for their black participants. A recipient of a MacArthur genius grant in 2019, Kaphar is both a torch bearer for a younger generation of artist, and a market darling of increasing power.

Today, more and more contemporary black visual artists are tirelessly working to confront racial injustice and the disparities reinforced by centuries of misrepresentation of black culture. Among these younger artists, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, just like Kerry James Marshall before her, is drawing on western art history to narrate a hybrid, post-colonial identity, and the complexity of the contemporary implications of the African diaspora. Nina Chanel Abney and Arcmanoro Niles are also young artists rooting their work in an autobiographic narrative, close to the political topics of abuse of power, racial conflict, police brutality and celebration of the diasporic Black identity. In these turbulent times, the necessity of representing the complexity of the racial and cultural dialogue is more crucial than ever, though it is a narrative that has been at the core of the Black artistic experience for centuries.

Relevant sources to learn more

Rising from Slumber: Narcosis, Creation and David Hammons’ Basketball Drawings

What Can Contemporary Caribbean Art Teach Us About Diaspora and Identity?

Read about the Harlem Renaissance

Learn more about Faith Ringgold in this interview with the New York Times