Articles and Features

Chamber Of Aesthetics: Revisiting The White Cube, Its Rules Of Display And Erosion of Influence

© Photo : Charles Wilp / BPK, Berlin © Artwork : The Estate of Yves Klein

By Adam Hencz

“Modernism’s transposition of perception from life to formal values is complete.”

— Brian O’Doherty

In the age of public art installations and immersive exhibition experiences, art is expanding beyond the confines of its traditional spaces and its associated physical boundaries. While artists are constantly restaging the space and pushing the limits of what we consider art, the modus operandi for exhibition-making, the modernist ‘White Cube’ paradigm is still worth bearing in mind today as a reference point to understand the forces that challenge it and foster change. The prominent Irish critic, Brian O’Doherty elevated the mythology of the pristine white exhibition space into public discourse in the 1970s, drawing attention to the white cube convention for gallery spaces, not as a blank or neutral container, but as a historical construct. Such was the incision of O’Doherty’s commentary the 1976 issues of the Artforum, containing the first part of his essays Inside The White Cube, sold out very quickly, as were its following volumes in ‘81 and ‘86.

In this “specific aesthetic formula”, as O’Doherty explains, the artwork is no longer limited only to what is depicted on its surface or by its own object quality, but that interpretation of the piece is also subject to an increasing self-consciousness from the viewer. According to O’Doherty the spatial arrangement also consumes the works – and the statements placed within them – to a degree that their context becomes content. This leap from plane to space, and from work to context positions the viewer – that O’Doherty calls The Eye – as the only inhabitant of this unshadowed artificial site. Time and social space are excluded from the experience of artwork and the isolation of this modernist phenomenology becomes complete.

The White Space

O’Doherty’s contemplation on the white cube phenomenon, however, offered little to understand its prehistory. A few decades later, art critic and art historian Walter Grasskamp attempted to throw light upon the hardships of determining the exact roots of the white exhibition space. One reason for our lack of knowledge is due to the fragmented documentation of early exhibitions and the use of colorless sketches or later black and white photographs to record installation views. Possibly, it was Gustav Klimt’s 1910 solo-show at the Venice Biennale that internationally popularized the idea of the white colored wall. Later in the 1920s discussions among constructivist artists and architects in which white spaces and their accompanying connotations of infinite space started to emerge. According to Alexis Joachimides’ dissertation it was the German museum reform from the Wilhelminian period to the Nazi era that prepared the way for the widespread use of white cube practice. While these issues were first addressed in Europe, where its modernist galleries were pioneers in the use of white walls in exhibitions, it was in the United States where this experimental model was embraced by the showing of art in public art institutions.

Institutional Changes

The museum wall began to shed its (often classical) decorative elements to mimic the interior design of private homes, and as the construction of new institutions increasingly shifted towards the international style of architecture. Museums around the turn of the 20th century started to address practical issues regarding the display and storage of their collections, and these significant changes in the museums’ built environment in turn opened up new ways of evolving curatorship. Even in the mid-19th century there were attempts to avoid display overcrowding in favor of giving the gallery audience and museum visitors more physical and mental room to focus on individual pieces. Beginning with the Impressionists, pictures put pressure on the frame and demanded a different model for showing. Exhibiting was moving towards more spaced out displays and the frame, as a firm convention for locking the subject into a hermetic perspective system, had become a fragile tenet. The museological shift toward aestheticism thrived in America with the construction of new museum buildings advocating a more tranquil viewing experience. In 1909 Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts moved into a new building, and a creamy shade of gray color prevailed over the entirety of the museum’s interior. The museum under Benjamin Ives Gilman’s leadership took small, but important shifts towards symmetrical hanging and designing spacious interiors designed to guard against the museum fatigue of overwhelming volume.

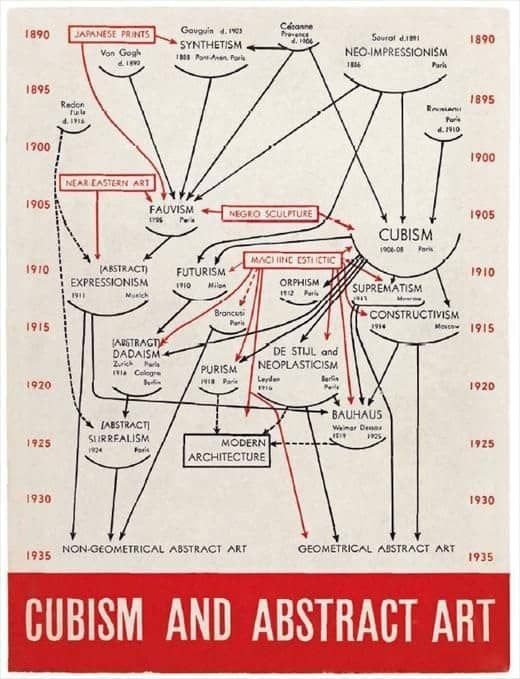

Whilst most pioneering exhibitions were framed within private art galleries and studios rather than given space by museums, with the 1929 appearance of the Museum of Modern Art in New York city the interpretive importance of museums and the curatorial role within them started to transform. In 1936, at the time when the first generations of modern art were beginning to disappear from the public sphere, the MoMA’s first, young director Alfred H. Barr organized an exhibition entitled Cubism and Abstract Art. It was the first sweeping survey exhibition of art movements in a museum context, a show that displayed art regardless of the periodization of artworks. Barr provided a narrative that continues to shape the presentation of modernism to this day, displaying artworks as autonomous and self-explanatory but within a wider context of dizzying cross-pollination. In many ways, Barr was allowing his analytic approach toward art, known alternatively as formalism, to flourish.

Photograph by Beaumont Newhall

It was a few years later, in 1939, when the various elements of the white cube eventually melded together, becoming the manifestation of the modern architectural and philosophical model of the gallery space. A new, custom-built home was erected for the MoMA on West 53rd Street in New York, designed by architects Philip L. Goodwin and Edward Durell Stone. Over the course of the first decade after its inauguration, the MoMA moved into three consecutively larger locations until it opened its midtown building, where it still stands today. The new MoMA building was New York’s endorsement of the international style as an approved image of the 20th century public building. The flexible floor plan and moveable partition walls were designed with the temporary nature of exhibitions in mind, and allowing for the greater versatility of a wide array of space permutations.

Artistic Considerations of The White Cube

The dominance of the sterile, blank gallery space was increasingly put to the test as the interaction between artists and the minimally articulated exhibition space started to escalate at the turn of the 1960s. Artists in general began to be fascinated by the conceptual possibilities of art and pioneering exhibitions and installations were questioning the autonomy of the white cube.

“The task of critical art then becomes one of reflecting and restaging

this space.” — Simon Sheikh

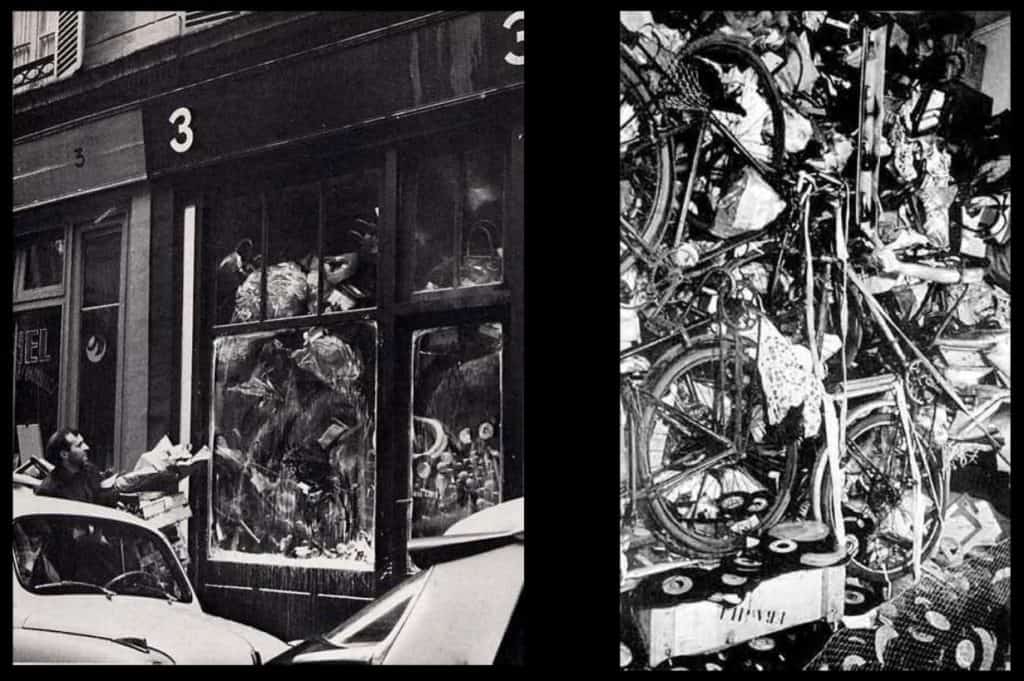

In April 1958, Yves Klein opened his private exhibition at the Iris Clert Gallery in Paris, called The Specialization of Sensibility in the Raw Material State into Stabilized Pictorial Sensibility, also known as The Void. The exterior wall and the canopy over the entrance was covered in blue fabric and the small 20 square meter gallery space was entirely painted pure white by the artist himself in a two-day isolation. The interior was completely emptied of objects and only a built-in cabinet and a white curtain remained. 3,500 private guests were invited to the show to be immersed in the void of the immaterial. A couple of years later Armand Fernandez orchestrated a counter exhibition The Full-Up, held in the same gallery. Arman would fill up the rooms with garbage, that Yves Klein declared as a “conclusive mummification of quantification”, that art has long forgotten.

In his essay Inside The White Cube, O’Doherty identified the changing artistic attitudes towards the white wall, citing the example of Frank Stella’s early painting and his exhibition in 1964 at Leo Castelli’s gallery. Stella’s works were breaking the accepted pictorial format of the rectangle, and his hanging of them was as pioneering as the works themselves, since his mode of display invited the white wall into his compositions as a means of, confirming their shape.

The pinnacle of such reevaluations happened in Chicago when Christo wrapped the entire Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art in tarpaulin in 1969. Like many artists of his era, Christo found inspiration in an arbitrary space and object, making the work itself a transformation of its intended use. As the press release for the exhibition declared: “With the whole idea of a modern museum and its usefulness somewhat up for grabs, Christo succeeds in parodying all the usual associations with a museum: a mausoleum, a repository for precious contents, as desire to wrap up all of art history.”

“As museums have become the primary program for architectural expression and the circulation of cultural capital, the gallery has progressively moved outside the art world to colonize other domains, from commerce to housing.”

— Jeremy Lecomte

As artists and the gallery space live in an ever changing symbiosis, both the legacy and critique of the white cube becomes ever more apparent. Whilst the white cube acted as a facilitator of new works and served as a point of departure for groundbreaking installations, it is also held responsible for supporting the long decried elitism propagated by the voracious commercial tendencies of the modern art world. On one hand, as the public display and arrangement of artworks allows for their decontextualization, the blank space can tend to alienate uninformed visitors, creating an impression of arrogant unchangingness and validation of the status quo. On the other hand, as art speaks a different language, it can also be highly communicative and intelligible without prior knowledge, bringing aesthetic issues together with social and political questions, and possible precisely because the display environment offers nothing other than a tabula rasa for this to take place. As experiences move away from the physical and into the digital or virtual, the role of the museum and art gallery and the creation of art history will increasingly part ways, especially with the exploration of different territories of display.

Relevant sources to learn more

Modes Of Display: The Changing Face Of The Exhibition Format

Simon Sheikh: Positively White Cube Revisited (e-flux journal)

Walter Grasskamp: The White Wall – The Prehistory of the “White Cube”’ (ONCURATING.org Issue #09)

What is Cubist Art?

A Tribute To The Unique Legacy of Christo and Jeanne-Claude

Installation Art: Top 10 Artists Who Pushed the Genre to its Limit