Articles and Features

Environmental Art: Changing Our Habits Or Just Illustrating What We Already Know?

By Adam Hencz

“The only thing we have to preserve nature with is culture . . . ”

— Wendell Berry

We worship and need it, sanctify and destroy it. Our relationship with nature is one of the key facets of our humanity, and so art, as one of the principal tenets of cultural production, is often tasked with explaining, illustrating and commenting on our complex relationship with the natural world. Environmental art is a term that has been applied to land art, but also more specifically to other forms of work that have ecological considerations at the heart of its messaging. Art of this type seeks to investigate this relationship, often embedding artistic practice in harmony with the natural environment. Environmental artists deeply consider the impact that they as individuals have on nature and do not sacrifice its health or wellbeing in order to create work. In the face of ever accelerating and increasingly dramatic climate change, it is no surprise that participating in the development of a planetary consciousness and being alert to environmental initiatives and sharing knowledge is something that is increasingly embraced by artists around the world. A reflection of this interest can also be seen in the increasing number of exhibitions in the past decade, devoted to the current state of the environment.

A Brief History Of Environmental Art

After World War II the art scene in the United States was dominated by abstract expressionism, exploring the unconscious and emphasizing how the gesture could embody the spontaneously emotional. The 1960s art world was seeking to break with the cult of personalized expression of American post-war abstraction. Self consciously urban, Pop art represented an antithesis of the natural world, and stood as an art form devoted to everyday culture, mass consumerism, and the affluent society. Similarly, minimalist art, process art, and ultimately, land art, proposed their own kind of conceptual approaches. The unwillingness to produce commodities and the awareness that each person has the potential and the power for change grew, with many artists increasingly drawn into political activism.

The first manifestations of what came to be known as environmental art grew from earth and land art, and began with fundamentally sculptural or performance-based projects in the American cultural crucible of New York and the open spaces of its Western deserts. The decade of the 1960s brought changes in the siting of artistic production itself, and, as opposed to using the artist’s studio as the sole location in which to create, environmental artists engaged the natural world in a much more active and immediate way, either by working in new ways outside, or by bringing natural materials into new settings. Although resistant to being seen as part of any distinct movement, the artists who first began to work with the landscape – Michael Heizer, Robert Smithson, Robert Morris, Dennis Oppenheim, Walter De Maria – all seem to have been dramatically influenced by socio-cultural currents of the time.

Environmental art also rethinks the importance of the exhibition space and seeks other places where art can both happen and exist. By looking for new and sometimes unique and surprising locations, artists not only remove the power from high-powered art-dealers, buyers, and from the art-market in general, but also question the role of an audience (and art buyers). This form of institutional critique also seeks to question the authority and power of museums and galleries that have historically controlled the production, viewing and sale of art works, with their influence also being key arbiters of market success of the artists fortunate enough to be patronised by their system.

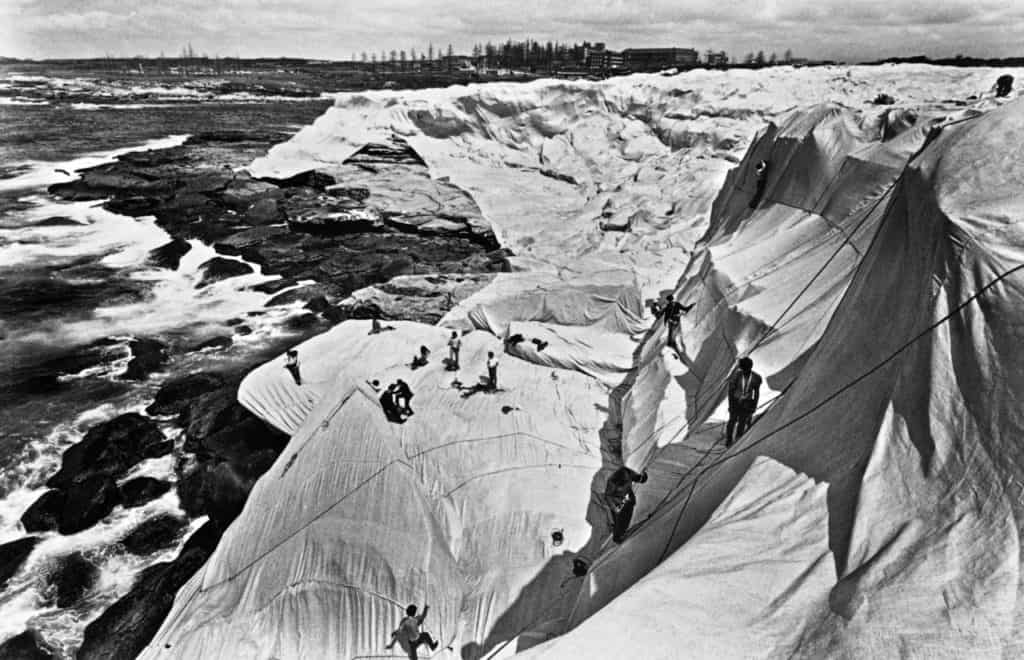

However, within environmental, land and site-specific art, there is a crucial distinction between artists who do not consider the possible damage to the environment that their artwork may create, thinking only about aesthetic merits, and those who do. While Spiral Jetty from 1969 created by Robert Smithson is considered his seminal work, the piece created permanent damage upon the landscape he worked with. When the European duo Christo and Jean-Claude temporarily wrapped the coastline at Little Bay the same year, the piece attracted a lot of negative criticism in environmental circles.

Art Of The Anthropocene

In 2016 the term Anthropocene was proposed to name a new geological epoch that we live in, that is primarily defined temporally by the devastating impact humans have had on our planet’s ecosystems. Artists have been incorporating the idea of raising awareness and calling for both individual and systemic action against environmental issues and global warming for decades now. Environmental art emerged as an offshoot of the environmentalist movement, with individuals such as Nils-Udo, Jean-Max Albert and Piotr Kowalski paving the way in the 1970s for a form of art expression that aimed to explore relations between nature and the human world along with raising awareness of burgeoning ecological problems. As Nils-Udo says in his artist statement. “By installing plantings or by integrating them into more complex installations, the work is literally implanted into nature. As a part of nature, the work lives and passes away in the rhythm of the seasons.”

At the end of the 1970s and at the beginning of the 1980s, artists preferred public spaces and urban landscapes to localize their art works. Hungarian-American conceptual artist Agnes Denes is often referred to as “the grandmother” of the early environmental art movement. She emerged during the 1960s and ‘70s and created many environment-inspired, site-specific pieces. Her most famous work, titled Wheatfield, a Confrontation, was created during a four-month period in the spring and summer of 1982. With the support of the Public Art Fund, Denes planted a field of golden wheat on two acres of landfill near Wall Street in lower Manhattan, the area which was to eventually be developed into Battery Park City.

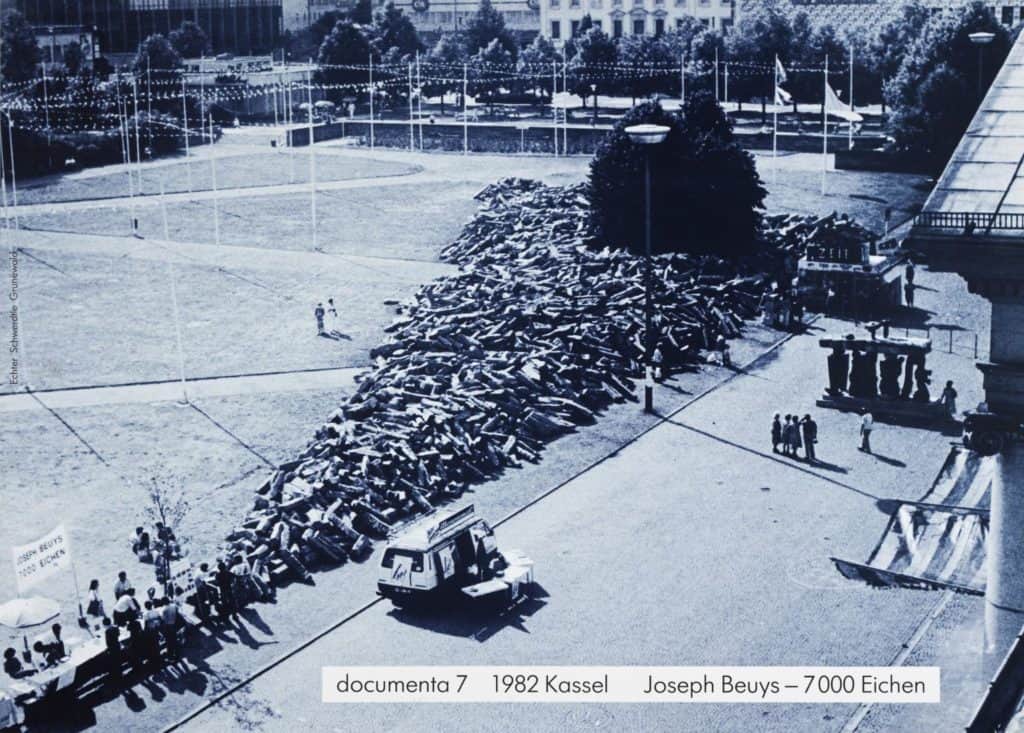

1982 marked the year for another pinnacle project for environmental art. Joseph Beuys proposed a plan to plant 7000 oaks throughout the city of Kassel at documenta 7, each paired with a basalt stone. The 7000 stones were piled up on the lawn in front of the Museum Fridericianum with the idea that the pile would shrink every time a tree was planted. The project, seen locally as a gesture towards green urban renewal, took five years to complete and has spread to other cities around the world.

The Responsibility Of The Contemporary Art Market

Areas most vulnerable to destruction: oceans, coral reefs and polar regions are becoming a particular subject of interest for artists. Architect, artist and entrepreneur Olafur Eliasson along with geologist Minik Rosing, created a temporary installation, Ice Watch, designed to serve as an explanation and a reminder of the impacts of climate change. On December 3, 2015, a circle of 80 tons of Greenlandic iceberg with a circumference of twenty meters was put on display at the Place du Panthéon during the 2015 UN Climate Summit in Paris. The installation thus heavily depended on weather conditions and lasted until the ice melted.

As the realities of a global climate emergency begin to sink in, biennials and art fairs increasingly echo and reflect the concerns of the world at large. The 58th Venice Biennial was produced under the overarching theme: May You Live In Interesting Times. The pavilion of Lithuania won the Golden Lion for Best National Participation with a climate change opera, Sun & Sea (Marina), a subtle message focusing on the mundane, unlike most works about climate change, which often simply shock and paralyze with the vastness of the problem. Visitors could participate alongside the performers, showing up in a bathing suit and towel to enjoy an ordinary day at an unusual beach.

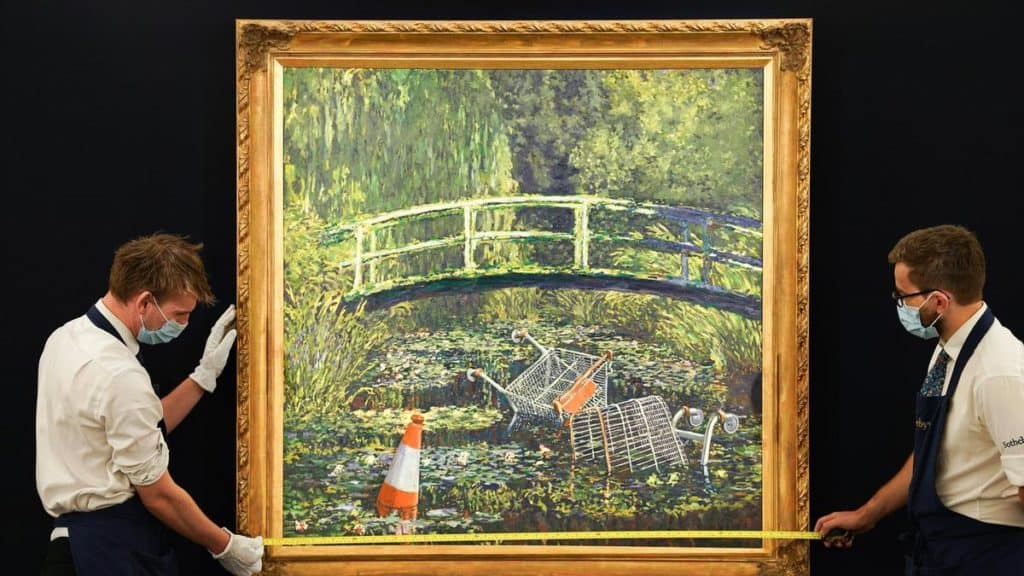

While we applaud climate change exhibitions for their efforts to raise awareness and hypothesize how humanity can approach the climate crisis, one can’t overlook the notion that environmental art runs the risk of simply being increasingly commodifiable because of its pertinence, timelines, and vogueish nature, as opposed to an agent of genuine change. The forthcoming of auction of Banksy’s Show Me The Monet is a case in point. Emblematic of the artist’s somewhat dim view of humanity and dystopian view of modern society, the work shows Monet’s famed Japanese garden at Giverny as a fly-tipping venue, complete with traffic cones and upturned shopping carts dumped in the idyllic scene. Estimated to achieve a price of up $6.5m, is the work representative of our collective conscience, or merely a clever visual pun and ultimate luxury good? If the current pandemic has shown us anything, it is that our social and urban fabric is overdue a reformation and renewal, giving rise to proposals and practices that could prevail in a post-pandemic art world.