Articles and Features

Artists In Residence: The Studios of The Abstract Expressionists

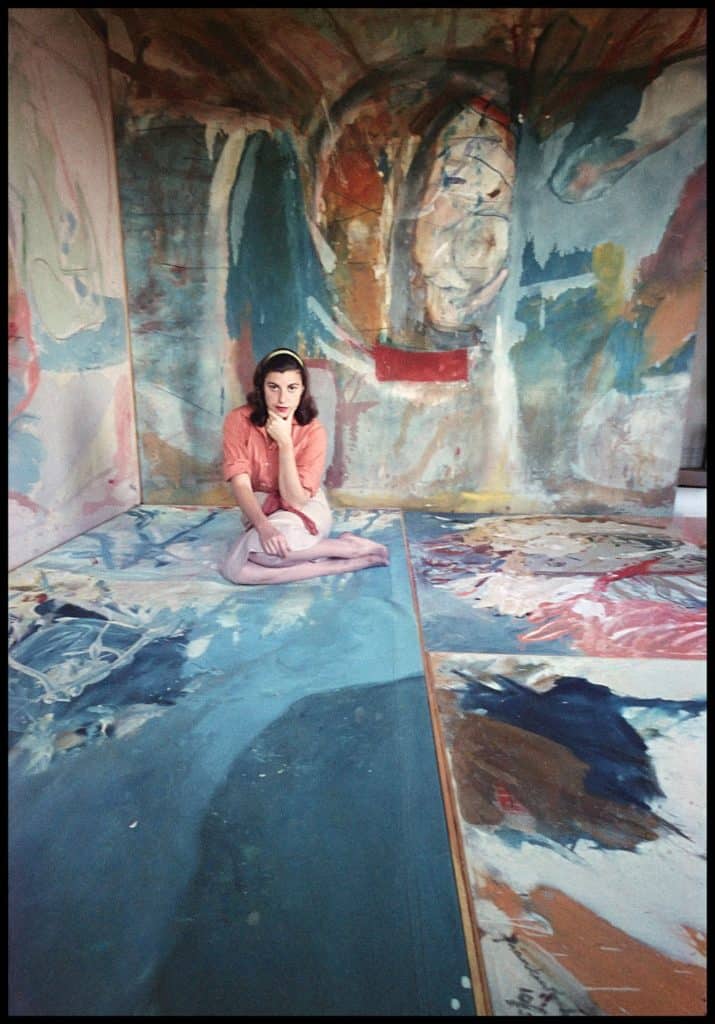

© Burt Glinn, Magnum Photos

By Adam Hencz

Our Artists In Residence series is dedicated to the photographic documentation of artists’ workspaces, in the company of their creatively striking residents. We offer a glimpse of the innermost environments some of the greatest modern and contemporary artists lived and created in. The series unveils everything from the intimacy of urban ateliers, through the pleasant creative mess of remote spaces, and hints at the personal lives of the individuals beyond their well-known artistic production. The first week, we visit the studios of Abstract Expressionist painters of the ‘50s and ‘60s in New York City and its vicinity. Photographers and photojournalists like Burt Glin, Gordon Parks and Hans Namuth preserved the working life of Helen Frankenthaler, the homestead studio of Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner as well as many of the shared studio spaces of Elaine and Willem de Kooning, often forging creative partnerships with the artists in the process.

© Burt Glinn, Magnum Photos

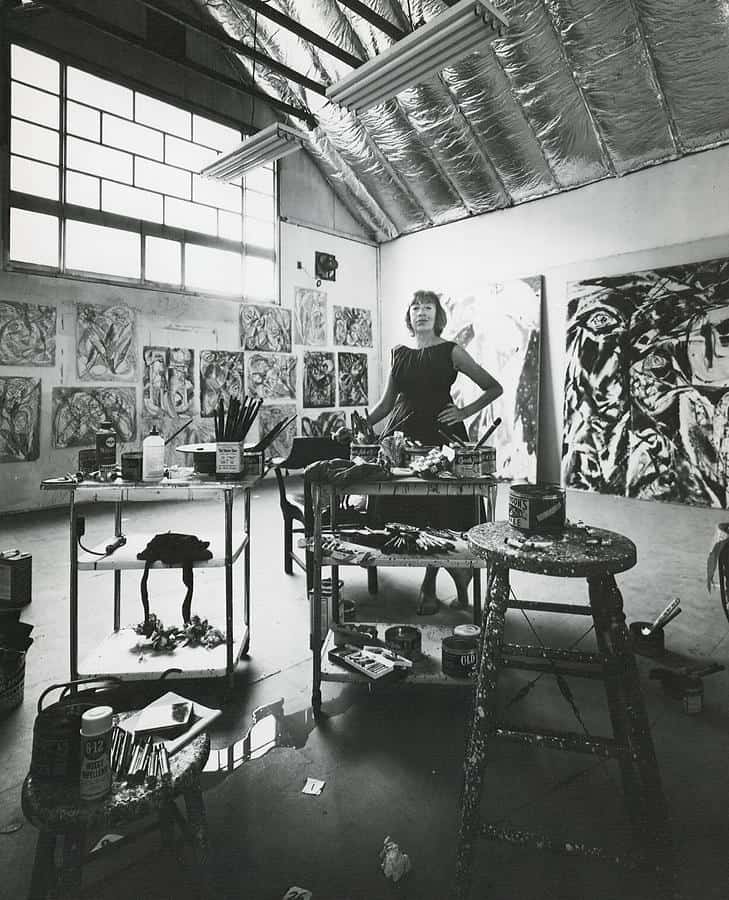

Helen Frankenthaler

Helen Frankenthaler began making a name for herself in the New York art world in the early ‘50s. She is remembered as a strong, feminine energy in a moment dominated by the masculine memory of artists like Willem de Kooning. and Jackson Pollock. At that time, Magnum photographer Burt Glinn was covering artists, poets and jazz musicians who created their art right in Manhattan. As a journalistic photographer, Glinn spent several years visiting studios, among them Helen Frankenthaler’s painting studio in 1957. The same year, Gordon Parks also photographed Frankenthaler for a spread in LIFE magazine, and the photographs have since become infamous representations of the gendered reality of the American Abstract Expressionist community. Following her invention of the breakthrough soak-stain technique and completion of works like her 1952 Mountains and Sea, Frankenthaler revisited Abstract Expressionism in the late 1950s, having moved in a different direction.

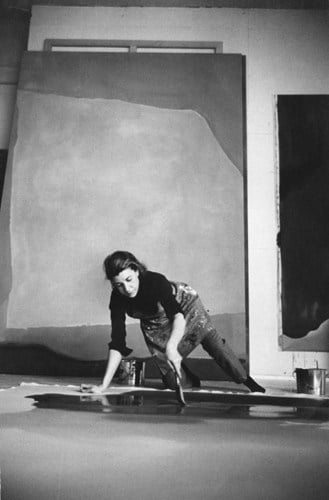

Photo by Tony Vaccaro

After a period of daring experimentation with oil paints and composition, and the exploration of symmetrical paintings, she began to make use of single stains and specks of solid color against white backgrounds, often in the form of geometric shapes. Beginning in 1963, Frankenthaler began to use acrylic paints rather than oil paints because they allowed for both opacity and sharpness when put on the canvas. By the time Ernst Haas photographed her in 1969, she had done away with the soak-stain technique entirely, preferring thicker paint that allowed her to employ bright colors almost reminiscent of Fauvism.

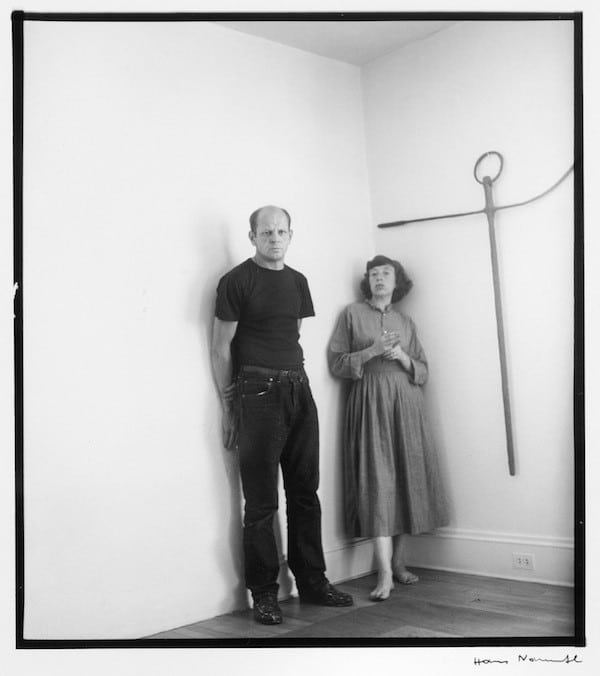

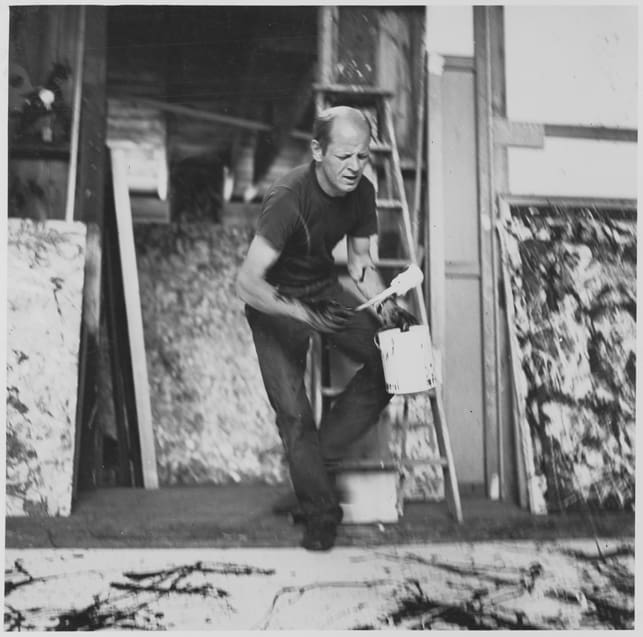

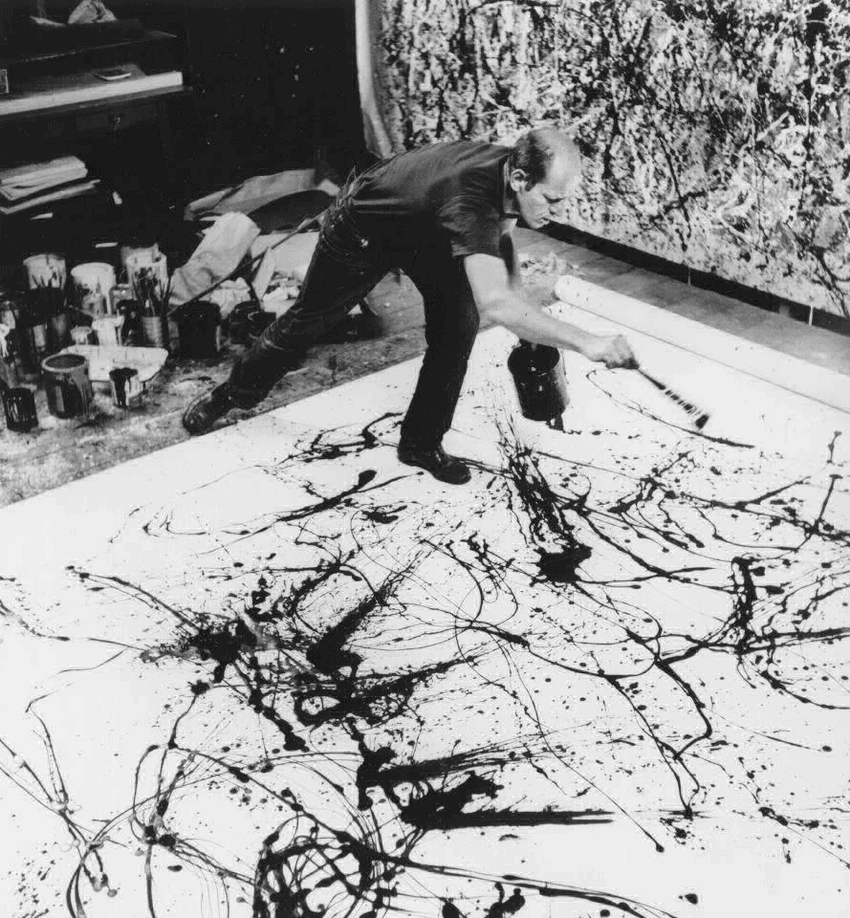

Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner

In 1945, Pollock married fellow artist Lee Krasner and moved from New York City to Long Island’s East End. With a loan from art dealer Peggy Guggenheim, they purchased a small homestead, typical of the 19th century farmers’ and fishermen’s homes, overlooking Accabonac Creek, near East Hampton. In this modest building, without heat or artificial light, Pollock painted his most famous drip paintings between 1947 and 1950. In the summer of 1950, German-born artist photographer Hans Namuth approached Pollock and asked the abstract expressionist painter if he could photograph him in his studio, working with his unique technique of painting. Krasner, aware of the importance of media attention, encouraged Pollock to work with Namuth, who eventually from July through early October 1950, took more than five hundred photographs of the artist.

As Pollock painted not on the easel, not on the wall, but on the floor, like the Navajo sand paintings that Pollock had seen in his boyhood in the Southwest, they allowed for a whole new kind of freedom: the freedom to move around the painting as he worked and articulated their surfaces with dripped and thrown paint. Namuth’s seminal photographs forever changed the way the public viewed Pollock’s paintings, revealed his deliberate process and captured the kinesthetic essence of his work. They “helped transform Pollock from a talented, cranky loner into the first media-driven superstar of American contemporary art, the jeans-clad, chain-smoking poster boy of abstract expressionism,” according to acclaimed culture critic Ferdinand Protzman. After Pollock’s fatal car crash in 1956, Krasner began to use the barn studio, and worked there for the rest of her life.

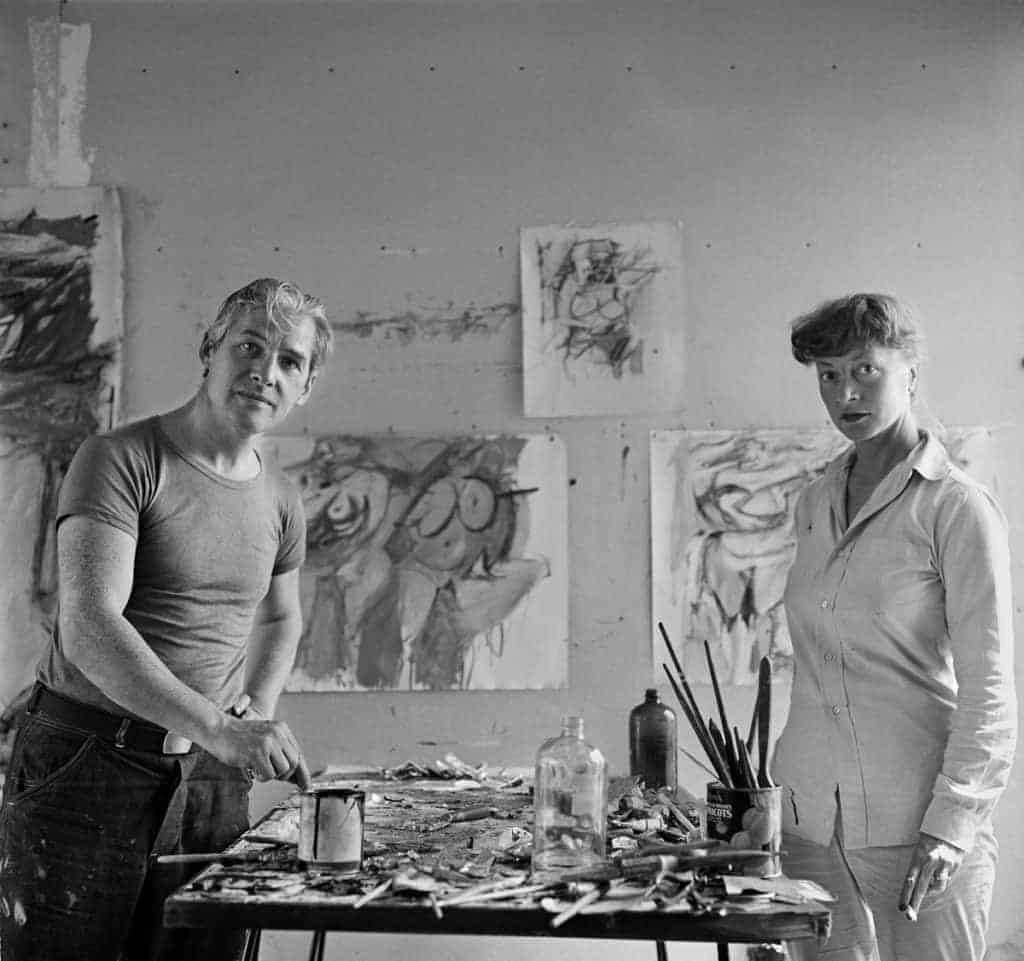

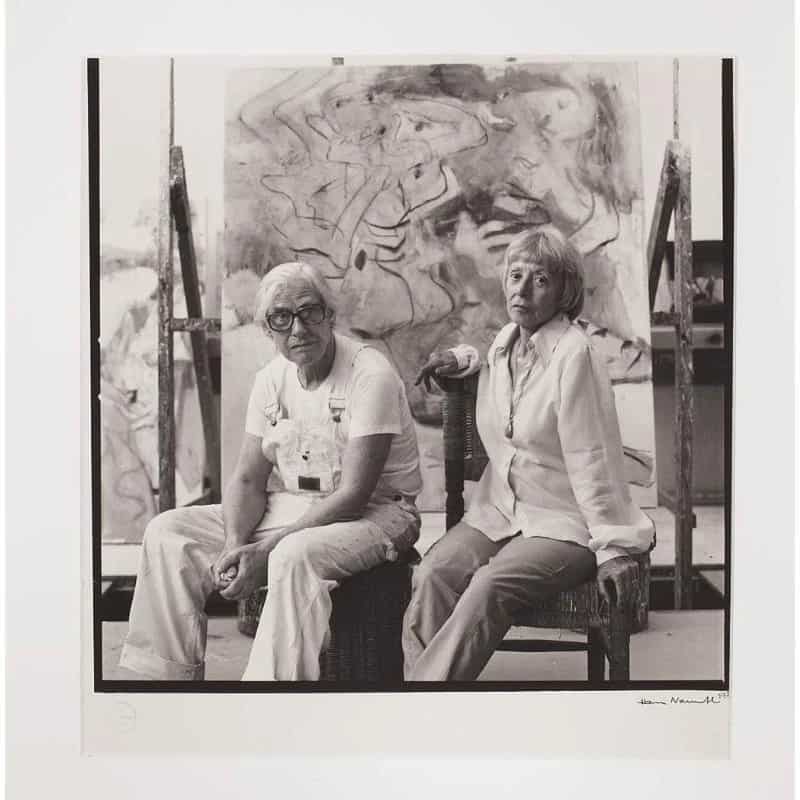

Elaine and Willem de Kooning

In the fall of 1938 Elaine was introduced to de Kooning at his studio by a mutual friend, when she was 20 and he was 34. The attraction was both immediate and mutual, thus shortly after meeting, de Kooning began giving Elaine traditional drawing lessons in his loft at 143 West 21st Street. He was rather harsh about her work but they would often work and do exhibitions together. As starting to be adulated by his peers, he and Elaine would go out together, to friends’ apartments and to Cedar’s Tavern, a dive bar in Greenwich Village popular among artists like Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner and Larry Rivers. When they married in 1943, she moved into his loft and they continued sharing studio spaces. Elaine and Willem had a well-known open marriage; they both were casual about sex and about each other’s affairs. Elaine promoted Willem’s career often by having romances and making portraits of men who could help: the prominent art critic Harold Rosenberg, and the ARTnews editor Thomas B. Hess. Willem as well had engaged in various casual affairs throughout their marriage.

Elaine and Willem both struggled with alcoholism, which eventually led to their separation in 1957. While separated, Elaine remained in New York, struggling with poverty, and Willem moved to Long Island and dealt with depression. Despite bouts with alcoholism, they both continued painting. Although separated for nearly twenty years, they never divorced. Willem moved from New York City to East Hampton, Long Island, in 1963 where he personally designed and built a studio and home. He would settle there permanently in 1971 and ultimately reunite with Elaine in 1976.

Relevant sources to learn more

Art Movement: Colour Field Painting

Art Movement: Abstract Expressionism

Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center

The Willem de Kooning Foundation