Articles and Features

Jo Van Gogh-Bonger: The Woman Who Made the Legend

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

By Wieland Rambke

“I would think it dreadful to have to say at the end of my life, ‘I’ve actually lived for nothing, I have achieved nothing great or noble.’”

Jo van Gogh-Bonger

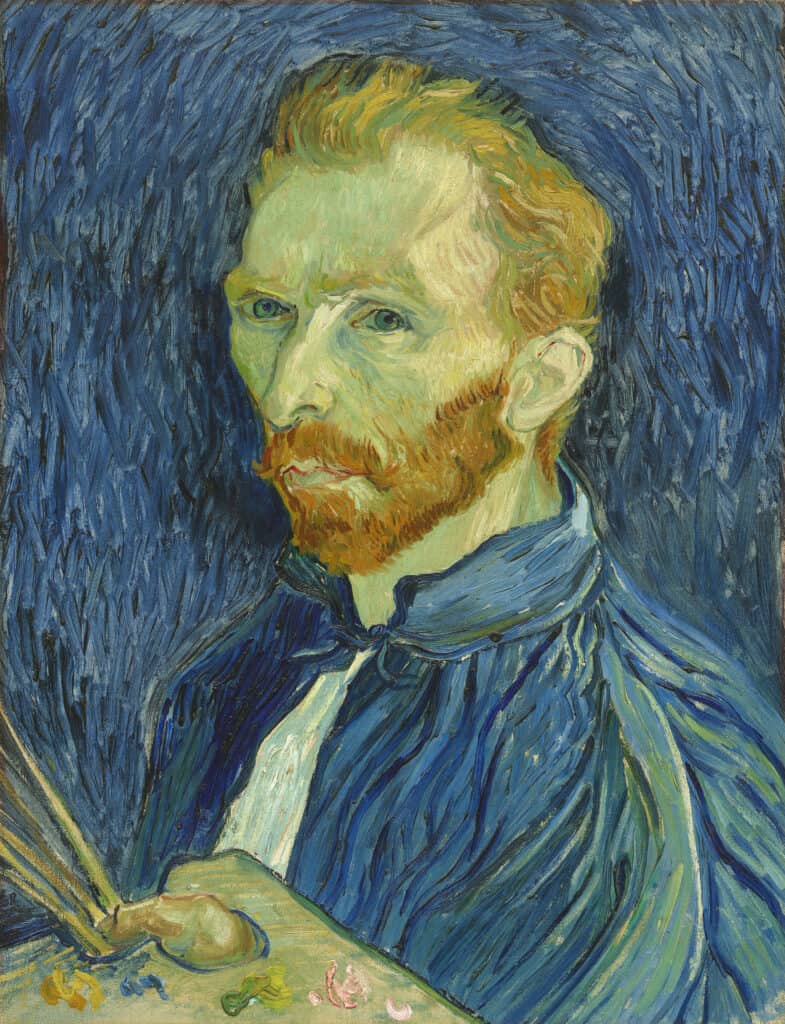

For most of art history, the psychology of the artist has played a subordinate role, and in the 19th century, technical excellence was still favoured over unique personal expression: the artist and their work were expected to be two separate entities. Today, the artist as a suffering genius is a cultural trope, and one of its most persisting images is Vincent van Gogh.

But how could a complete outsider like Van Gogh, unrecognized in his time, mentally unstable, prone to alcohol abuse, and almost compulsively burning bridges with those who might have helped him on his creative path, ever attain the mythic status that he holds today? The answer lies with a woman named Johanna Bonger.

Jo van Gogh-Bonger

When in 1885, Johanna met Theo van Gogh, Vincent’s younger brother, she was 22 years old, bound for an uneventful life as a language teacher, a life that could impossibly satisfy her strong passion for art and intellectual pursuits. As she told her diary at the age of 17: “I would think it dreadful to have to say at the end of my life, ‘I’ve actually lived for nothing, I have achieved nothing great or noble.” Theo van Gogh was love-struck and proposed to Johanna after only having met her twice. Initially, Jo – as she used to call herself – was annoyed: how could someone approach her like that when he barely even knew her?

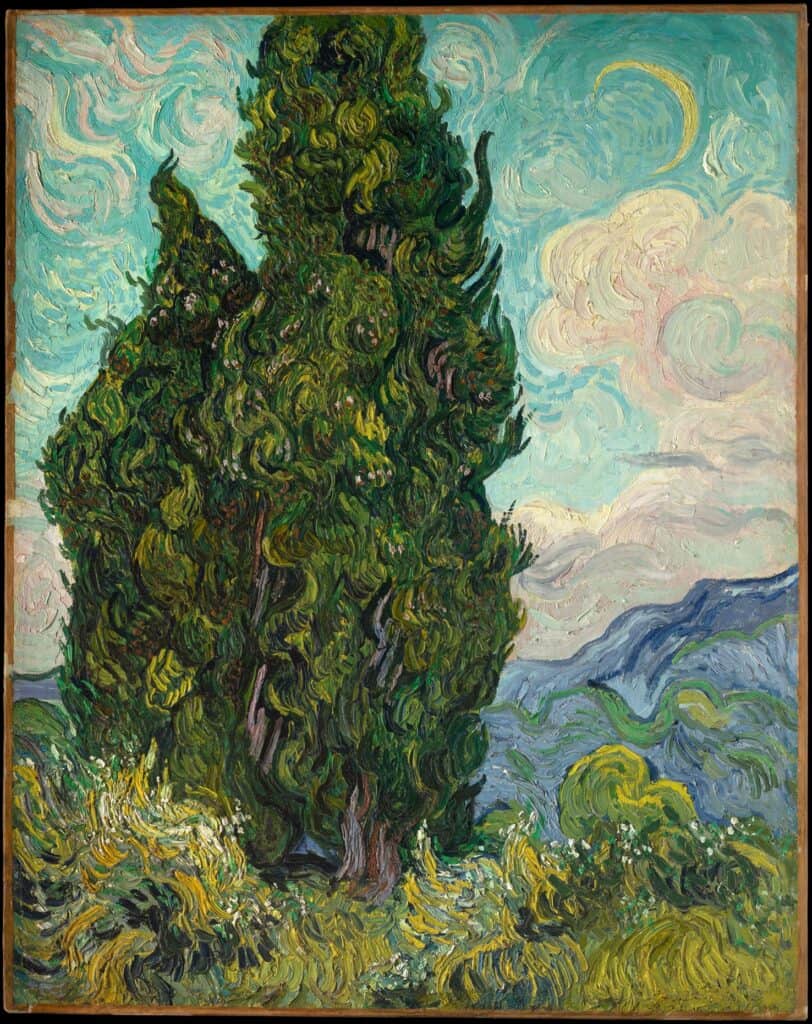

But Theo persisted, and in 1889, the two eventually got married. Theo, an art dealer, introduced Jo to the buzzing culture of Paris where the two lived together. He had specialized in dealing with Impressionist paintings, a then completely novel style that had generated much controversy since it was so fundamentally at odds with the then-dominant academic doctrine of realism. Impressionism was vivid and fresh, and it challenged the monolithic status of academia. But the home of Jo and Theo was filled with paintings that marked another, even more radical approach to painting: the works of Vincent van Gogh. At the time, Vincent had reached his most productive period, and for about two years he would create painting after painting in rapid succession, and then send them to his brother Theo.

A Raw and Gentle Touch

The paintings were beyond classification: vibrant colours applied so thickly they lent the paintings an almost sculptural quality. Trees and landscapes were painted with a raw sensitivity unknown in art at the time. This was clearly the work of a unique mind that had a magical view of the world, an attempt at relating the inner life of what he saw in the things around him. This practically animistic perspective comes out particularly well in his still lifes and nature paintings. All was life, and everything was alive. One can always tell how Vincent felt on that particular day just by looking at his paintings. These paintings didn’t depict, nor illustrate: in relating the essence of what he saw, Vincent laid bare his own essence, right there on the canvas. This was raw emotion paired with unfettered artistic instinct.

But he was troubled, and struggling, mostly surviving on money sent from his brother Theo. Indeed, Vincent had himself tried to become an art dealer before, but he couldn’t reconcile his idealism with the demands and mechanisms of the art market. He had taken a dark path: he was drifting, a failed art dealer who became a failed minister, struggling with alcohol, his health deteriorating, his romantic life a series of disappointments and dead ends.

And so he became a self-proclaimed painter, unknown yet fully devoted, filled with gnawing self-doubt yet painting incessantly, always in fear of the next mental breakdown, scared that another fit might spell the end of his creativity altogether. Theo was one of the few stable connections in his life. For years, the brothers had been writing letters to one another, and Vincent didn’t hold back on his fears and feelings. And Theo shared all his brothers’ troubles with Jo.

Bliss and Sorrow

For Jo, it was a period of deep bliss as she was swept up in the cultural exuberance of fin-de-siecle Paris. In 1890, her son was born; he was named Vincent, after his uncle. That year, Vincent van Gogh came to Paris for a visit: Jo, who had only heard of his trouble and turmoil, to her surprise met a man who appeared strong, healthy, and cheerful. Apparently, Vincent had finally found a goal and a direction in his life by fully subjecting his life to his art. Everything else was secondary now, and this had liberated him.

A few weeks later, at the age of 37, Van Gogh took his own life. His suicide had come as a complete shock to Jo and her husband. Today, there is evidence that Van Gogh might not have committed suicide, but rather was killed in an accident by a young farm boy who later told lies to save himself, knowing this wouldn’t have made a difference to the young family in Paris. Theo was devastated: his brother’s paintings were just starting to gain recognition as they had been exhibited in smaller group shows. Shortly thereafter, Theo suffered a complete collapse and was admitted to a psychiatric hospital. He died after a few months of horrific anguish. Jo was alone with a child now and had to make sense of her life on her own terms.

On Her Own Terms

Jo took matters into her own hands, leaving Paris and the flat she had lived in with Theo; what remained were some 400 Van Gogh’s paintings and hundreds of drawings. She moved back to The Netherlands to run a boarding house but, before leaving, she made contact with painter Émile Bernard, determined to get Vincent’s work known and organize a solo exhibition. While Bernard urged her to leave the paintings in Paris, she insisted on taking them with her. A highly pragmatic person, yet driven by her dreams and aspirations – no matter how unrealistic they might have seemed at the time – she was a unique combination of level-headedness and instinct, and would not let anyone handle this except herself.

Jo had her fair share of problems, too: she was riddled with insecurities and had a tendency to be highly self-critical. Nevertheless, she was able to see things in perspective, and there was no way she would let any inner or outer resistance stump her plan: to reveal the beauty of Vincent’s work to the world.

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

The First to Truly Understand

The resistance was plentiful for a young woman who had no viable artistic or business background and still wanted to make herself heard. The voice of a woman like Jo would simply be dismissed on the basis of what she was, not what she was capable of doing. But none of that mattered to her. The room she lived in was filled with Van Gogh paintings, and she started to read the letters between Theo and his brother. First, out of grief, and to come to terms with the last two wild years she had just experienced. But gradually, her attention shifted to Vincent: his struggle and turmoil as a misunderstood genius would resonate with her own experience of being an outcast to the art world.

She began to teach herself the basics of art criticism. At the same time, her study of the letters revealed to her what lay at the heart of Vincent’s paintings: his own soul; ultimately finding the deep connection between the inner world of an artist and his work. Vincent’s enormous sensitivity was what drove his approach to painting. While Impressionism was occupied with how things looked to the eye, Vincent painted the effect they had on his soul. Emotions are raw and primordial, and so were his paintings. Even the most radically progressive critics often dismissed his work as something merely “unrefined;” they simply failed to see the beauty. But Jo would make them understand.

A Fruitful Effort

Being marginalized herself, she identified with the downtrodden and joined the Dutch Social Democratic Workers Party, appalled at the working conditions of the lower class. In 1901, she remarried, this time with Dutch painter Johan Cohen Gosschalk. And she kept pushing, going from critic to critic, from gallery to gallery, and bringing the word out about Vincent’s work. As a language teacher, she spoke French, English, and German fluently, which greatly helped her handle things independently. And after years of persevering, her determination began to show fruit. Galleries in Paris, Berlin, and Copenhagen started to show Van Gogh’s paintings. She never sold them cheaply, and always kept the most impressive work back. Before too long, more than a hundred shows across Europe had exhibited Vincent’s work. The highlight was a solo exhibition in Amsterdam, fully organized by herself.

But even this was not enough: in 1914, she published the first volume of “The Letters to Theo”, a fascinating read in its own right, reinforcing her point that the artist is indistinguishable from the artwork. This publication helped greatly in making Van Gogh known. Her second husband had died just a few years prior, in 1912. Widowed again, Jo would not give in to grief or self-pity. In 1916, at the age of 54, when most people begin to settle down for good, she moved to New York City, determined to take Van Gogh to the US.

The Return

In 1919, Jo returned to Amsterdam, somewhat disappointed with the lack of appreciation in American critics, but she refused to become bitter. In 1925, she died in the Dutch town of Laren, aged 62. Had it not been for her unwavering strength in the face of adversity, the work of Vincent Van Gogh would be unknown today, and it all goes back to Jo, an outsider who would not allow social circumstances to dictate her life.

Relevant sources to learn more

More on Johanna van Gogh-Bonger

Most famous paintings by Vincent van Gogh

Discover the life and work of Vincent van Gogh at Van Gogh Museum