Articles and Features

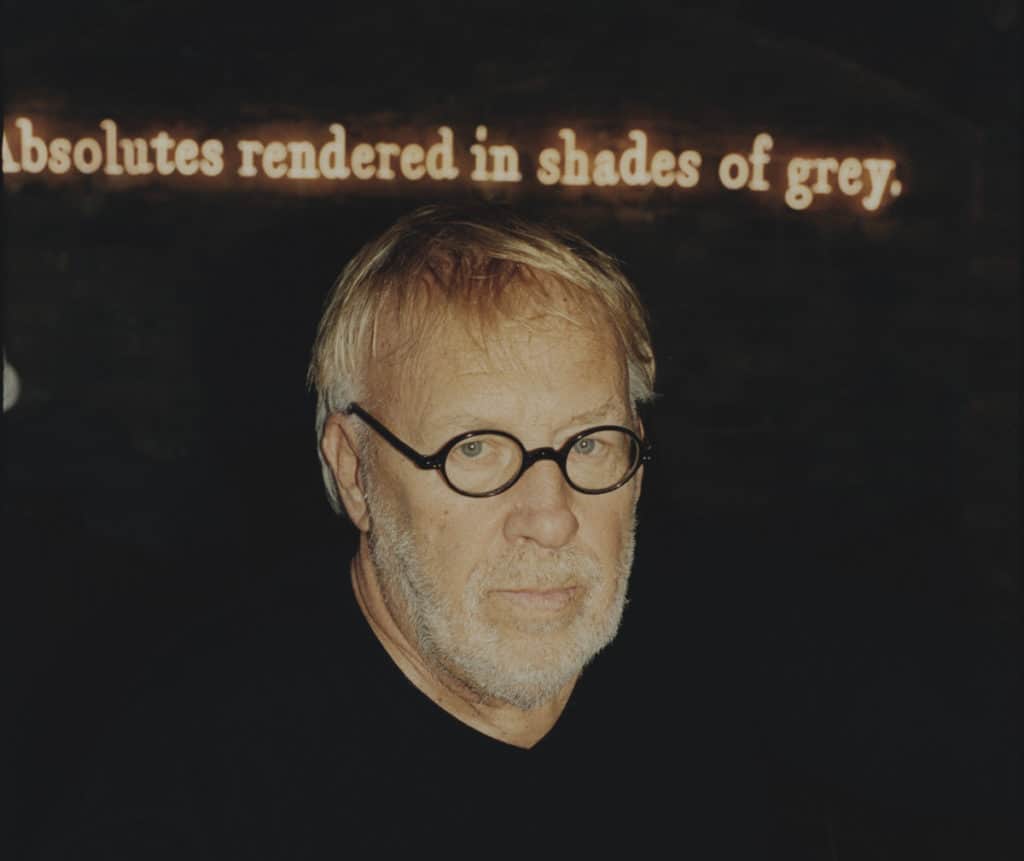

Joseph Kosuth – Shifting Art from “How” to “Why”

By Shira Wolfe

“The actual works of art are the ideas.” – Joseph Kosuth

Joseph Kosuth is one of the pioneers of installation art and conceptual art, a movement which emerged during the 1960s and 1970s and redefined the notion of the art object. Kosuth was among the first artists to employ appropriation strategies, language-based works, photography, installations and public media. He also wrote some of the earliest theoretical texts supporting these approaches. Throughout his career, Kosuth has continually explored the production and role of language and meaning in art.

Joseph Kosuth, New York and Conceptual Art

Kosuth, born in Toledo, Ohio in 1945, moved to New York in 1965 where he enrolled in the School of Visual Arts. He quickly abandoned painting in favour of conceptual works, which he first showed in 1967 at the exhibition space he co-founded, known as the Museum of Normal Art. That year, Kosuth organised the exhibitions Nonanthropomorphic Art and Normal Art, where he and Christine Kozlov showed their works. Significantly, in his notes accompanying the exhibition, Kosuth wrote: “The actual works of art are the ideas.” That same year, he exhibited the series Titled (Art as Idea as Idea). This series consisted of words that were at the core of the debate surrounding the status of modern art, rather than of visual imagery. The words at the core of the exhibition included “meaning,” “object,” “representation” and “theory.” In 1969, Kosuth had his first solo show at Leo Castelli Gallery in New York, and became the American editor of the Art and Language journal.

Art After Philosophy

In 1969, Kosuth published his seminal essay “Art After Philosophy,” which argued that traditional art-historical discourse had reached its end. He proposed a radical investigation of the way in which art acquires its cultural significance and its status as art. Kosuth stated: “Being an artist now means to question the nature of art. If one is questioning the nature of painting, one cannot be questioning the nature of art… That’s because the word ‘art’ is general and the word ‘painting’ is specific. Painting is a kind of art. If you make paintings you are already accepting (not questioning) the nature of art.” During this important formative period in his work, Kosuth followed through with what Marcel Duchamp had proved with his readymades: art presupposes the existence of an aesthetic entity fulfilling the criteria of what should be art. As was the case with Duchamp’s readymades, he declared them to be art and they became art. Kosuth used a linguistic approach to explore these issues of the presentation and definition of art.

Joseph Kosuth and the Philosophy of Language

Between 1971 and 1972, Kosuth studied anthropology and philosophy at the New School for Social Research, New York. There, he was particularly influenced by the philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein, whose writing on the philosophy of language strongly influenced Kosuth’s work between the late sixties and mid seventies. He began to devote his work to exploring the use of words instead of visual imagery, as well as the relationship between ideas, words and images. He borrowed the term ‘Investigations’ for his art in that period from Wittgenstein, believing that philosophy could only survive through being art. ‘Investigations’ were like a protection of the activity of art, a protection from art becoming decoration, fashion, or part of the art market, which was quite pervasive in the 1960s. Kosuth believed, like Duchamp, that art was an intellectual activity.

“What I feel my work introduced – or conceptual art in general – was a shift from “how” to “why.” – Joseph Kosuth

Iconic Works

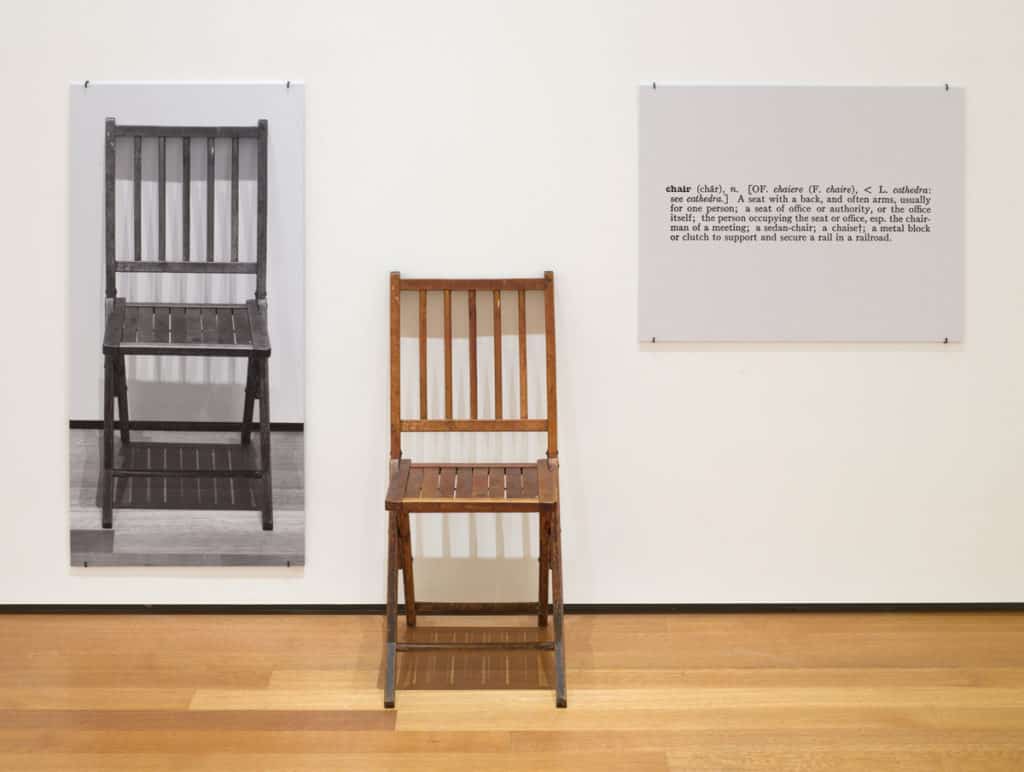

One and Three Chairs (1965)

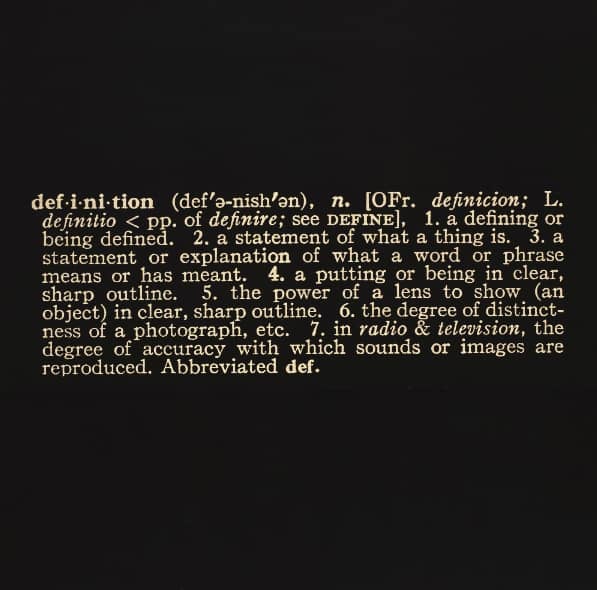

One of Kosuth’s best-known works is One and Three Chairs (1965), which is his visual expression of Plato’s Theory of Forms. The piece features a wooden chair, a photograph of the chair, and a dictionary definition of the word “chair.” According to Plato’s theory, non-material abstract forms (or ideas) are the most fundamental kind of reality, as opposed to the physical world. In this piece, Kosuth investigates this theory by representing a chair in these three different ways.

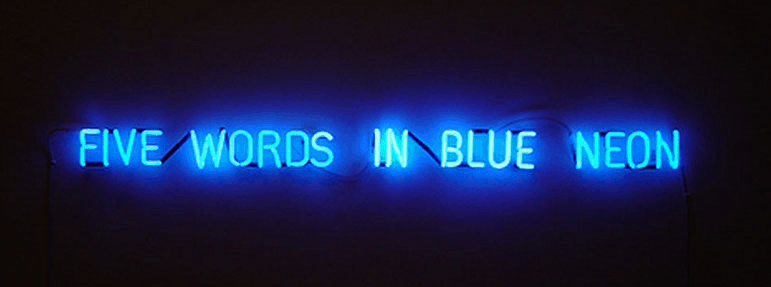

Five Words in Blue Neon (1965)

Joseph Kosuth uses colour to demonstrate the limits of language. In his words: “What is better for demonstrating the limits of language than the definition of a color? No text is more tortured in such a concise way, there really is no better place to experience the limits of language.” This can be seen is his famous work “Five Words in Blue Neon,” which consists simply of blue neon lights spelling this phrase. When Kosuth created this work, he intended to branch out beyond the canvas, creating something that is arresting, something that grabs one’s attention.

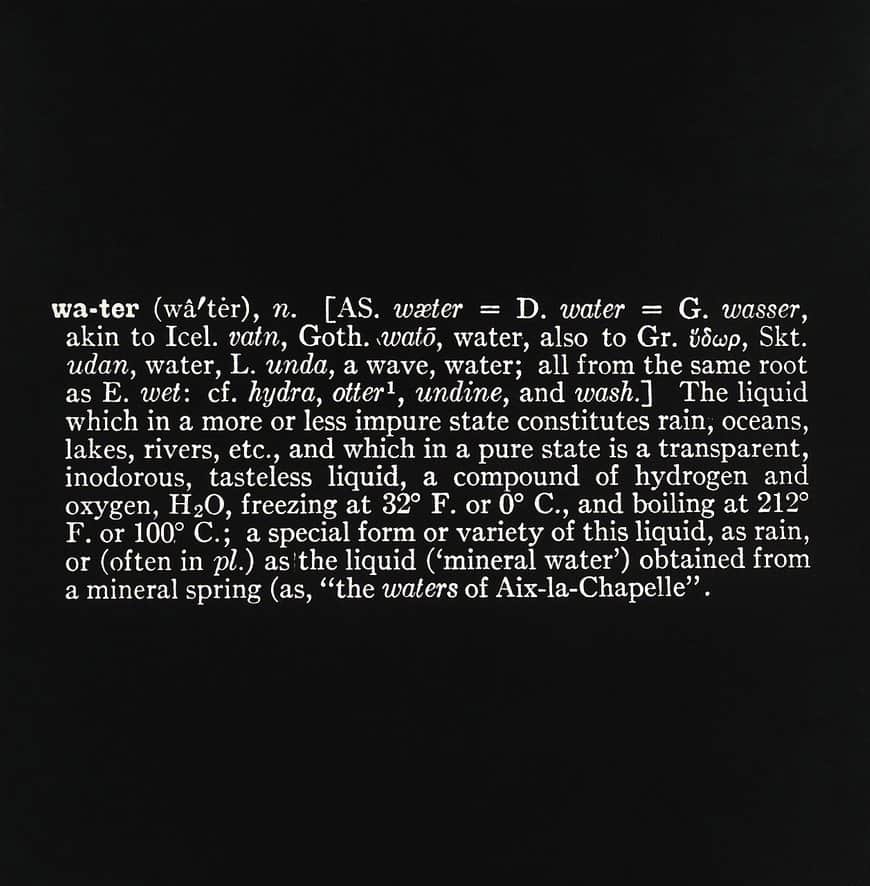

Art as Idea as Idea (1966-1968)

In his series Art as Idea as Idea, all objects and images are removed in favour of definitions taken from dictionary entries. In doing so, Kosuth attempts to emphasize how language has the potential to purely convey meaning. He believes that any traces of the artist’s hand should be eliminated from the production of art, so that ideas may be expressed directly, immediately and wholly. The work of art, for Kosuth, is the definition of the given word. For the purpose of presentation, Kosuth asks that his original cut-out dictionary entry is photographically enlarged to a specific dimension, each time the work is exhibited.

Double Reading (1993)

For a 1993 exhibition at the Margo Leavin Gallery in Los Angeles, Kosuth exhibited a series in which he worked with cartoons. He took cartoons like Blondie, Wizard of Id, and Calvin and Hobbes, blew them up and silk-screened them on laminated glass with neon. He then added quotes to each of the works by philosophers like Leibniz and Kierkegaard, matching the right cartoon with the right philosopher. When he arrived at the opening, a few Hollywood lawyers who were his collectors rushed up to him, asking whether he had obtained permission to use the cartoons. Kosuth answered: “No, no, I didn’t. And I didn’t get permission from Kierkegaard either. I pointed to the cartoon and I said, ‘That’s not my work.’ And then I pointed to the quote and I said, ‘That’s not my work either. Those are props. My work is the gap between the two. It’s the surplus meaning that goes together to create.’

Joseph Kosuth’s immense influence on the art world is best summed up in the artist’s own words: “What I feel my work introduced – or conceptual art in general – was a shift from “how” to “why.” – Joseph Kosuth