Articles and Features

Living Off Of Blue-Chip Works: Museum Deaccessioning Amid Crisis

By Adam Hencz

While letting go of artworks has allowed museums to improve their diversity of collections, attract more traffic to new works, and help continue operations, the past year saw an unprecedented number of deaccessions from museums. Loosened sanctions relating to deaccessioning caused museums like the Baltimore Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum and the Palm Springs Art Museum in California to sell major works at auction. The suspension of the rule came at a time when many institutions are struggling financially under the burden of the ongoing health crisis.

Rules of deaccessioning

The general consensus on deaccession and the process of liquidating works to generate funds has long been met with controversy in the art world. As museums have a moral responsibility to serve the public interest, deaccessioning works from the permanent collection is explicitly discouraged by museums’ own mission statements, professional directives and usually by donors’ wills, besides being governed by strict policies.

In general terms, deaccessioning may be contemplated if the work is of poor quality, the work is a duplicate, or determined to be fake or fraudulent. What is more, public museums in the United States are generally only permitted the use of proceeds from such sales to acquire new works for the museum’s collection. For what concerns the United States, there are no official laws guiding deaccessions, but most museum officials adhere to guidelines set in place by industry groups like the Association of Art Museum Directors, the AAMD, that is considered as the premier governing membership organization for art museums.

Shortly after widespread lockdowns, last April the AAMD Board of Trustees approved a resolution to provide additional financial flexibility to art museums during the pandemic crisis. First and foremost, the AAMD stopped sanctioning the use of income from donations like philanthropic giving or large gifts until 2022. Such donations often come with restrictions on use, if used for general operations, including necessary expenses such as staff compensation and benefits. The other prong that has eventually stirred up the art world since then is that institutions may now use proceeds from deaccessioned works in order to support direct care of museum collections, and the onrush of this opportunity encouraged institutions to sell works from their holdings in order to raise capital amid financial strains caused by the pandemic.

Recent deaccessioning plans in the US

Last fall, as part of its long-term collection review, the Brooklyn Museum was putting works of art up for auction at both Christie’s and Sotheby’s simultaneously, including works by Degas, Dubuffet, Matisse, Miró, and Monet. The proceeds from the sales were secured in the museum’s collection care fund and then invested to pay for the future care of the collection. “This effort is designed to support one of the most important functions of any museum—the care for its collection—and comes after several years of focused effort by the museum to build a plan to strengthen its collection, repatriate objects, advance provenance research, improve storage and more,” said Brooklyn Museum director Anne Pasternak in a statement.

The museum has faced scrutiny and has been criticized for taking a “conservative approach” towards the temporary relaxing of rules; however, museum leadership argued that even though the works for sale are considered masterpieces, they did not qualify to be unique enough to further define the collection, neither relevant enough to diversification efforts. The Brooklyn Museum is one of several institutions to deaccession important works last fall under the relaxed rules, including the Everson Museum in Syracuse, which sold a Jackson Pollock painting at a Christie’s New York evening sale last October. The sale garnered $13 million to establish a fund devoted to purchasing works by “artists of color, women, and under-represented, emerging and mid-career artists”.

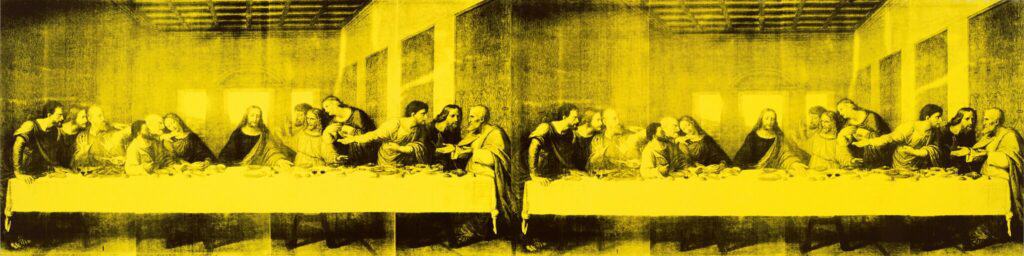

Perhaps the most controversial recent deaccession plans are those connected to the Baltimore Museum of Art, which announced in October to sell works by Brice Marden, Clyfford Still, and Andy Warhol at a Sotheby’s auction. The works were to bring in a collected $65 million, but in a shocking last-minute move, the museum decided to halt its plans to sell the three works from its collection. The museum released a statement saying: “Our vision and our goals have not changed. It will take us longer to achieve them, but we will do so through all means at our disposal.”

The museum was going to put a substantial amount of the projected proceeds towards a fund that would kick off income that would allegedly contribute to the direct care of collections, including raising the salaries of several dozen staff members and additional money to purchase works by women and non-white artists to enter the collection but also to allow free admissions for special exhibitions, among others initiative. The critics expressed that the museum is using the rule changes to generate more funds for projects that do not necessarily fall under the endangered category, namely the direct care of the collection. To be more precise, the claim that the museum would use the sale of works to increase salaries seemed like a manipulation of the AAMD guidelines as it appeared to be an example of conflict of interest since the museum’s curators were involved in the deaccessioning proposition that would directly reflect on their payments.

In conclusion, to some museums deaccessioning offers increased financial security during a tumultuous period; to others, it can allow them to address a lack of diversity within their own collections. But given the widespread outpouring of criticism, US museums will seemingly have to navigate the complex process of deaccessioning under growing public scrutiny in the post-pandemic world.

Relevant sources to learn more

AAMD Board of Trustees Approves Resolution to Provide Additional Financial Flexibility to Art Museums During Pandemic Crisis

How ‘deaccession’ became the museum buzzword of 2020

Baltimore Museum of Art Calls Off Controversial Deaccession Plan Hours Before Sale

Current Events of Deaccessioning and Cries of Censorship Podcast by The Art Law Podcast

Read more on museums

What To Look Forward To In 2021: New Art Museums Opening This Year