Articles and Features

Lost (and Found) Artist Series: Norman Lewis

By Shira Wolfe

“I used to paint Negroes being dispossessed; discrimination, and slowly I became aware of the fact that this didn’t move anybody, it didn’t make things better.” – Norman Lewis

Artland’s Lost (and Found) Artist Series focuses on artists who were originally omitted from the mainstream art canon or largely invisible for most of their career. In our last edition, we featured Rose Wylie, the 86-year-old British artist who is currently the subject of renewed critical acclaim. This week, we explore the exceptional body of work of Norman Lewis, an African American artist who came of age in the time of the Harlem Renaissance, and who became an important voice in Abstract Expressionism.

Norman Lewis: The Early Years

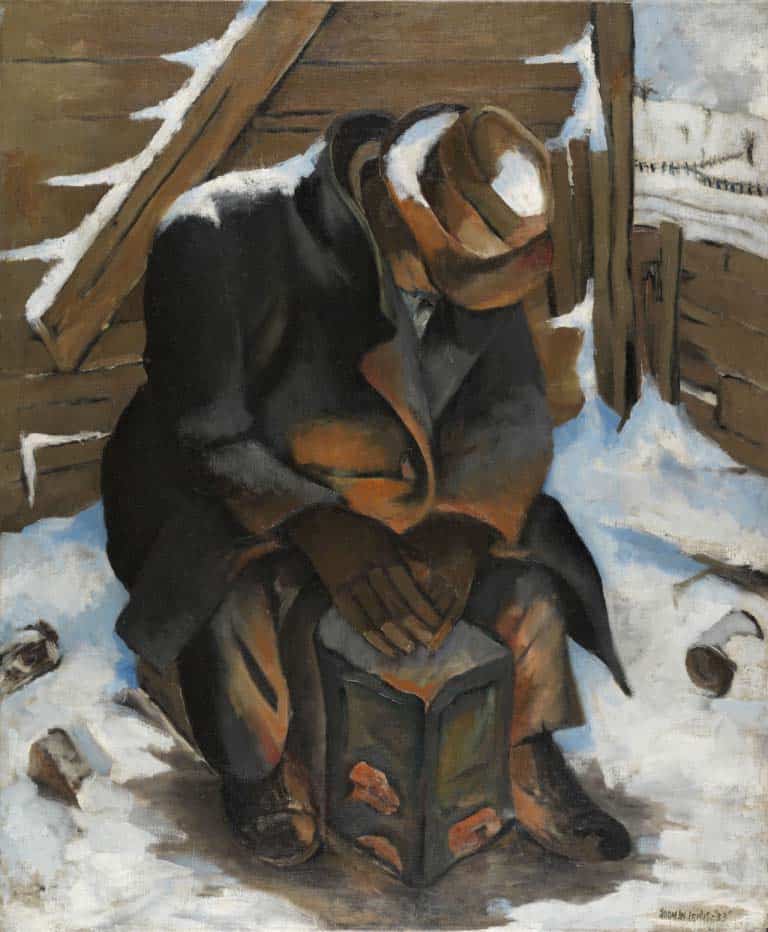

Born in Harlem, New York in 1909, Norman Lewis grew up in a neighbourhood that became a massive cultural hub. It was the birthplace of the Harlem Renaissance, which blossomed in the 1920s and 1930s. Lewis first studied art under the sculptor Augusta Savage, one of the key figures of the Harlem Renaissance. During the time of the Works Progress Administration and the Great Depression, Lewis taught painting at the Harlem Community Art Center, and painted in the social realist style. These figurative works depicted social topics like bread lines, evictions and police brutality. He believed that if people were to see what was actually happening to black people on a daily basis, it would change the way they thought.

In “The Wanderer (Johnny)” from 1933, we see a man huddled over a fire in the snow, warming his hands. “Police Beating (Untitled)” (1943) depicts a police officer standing over a black man, beating him with a club. The faces of the white onlookers have cartoon-like features and look excited, even happy, while the bloody face of the black man and the face of the police man are both blurred and indistinct, caught in the horror of this moment of violence. These are powerful works, yet, during the mid-‘40s, Lewis abandoned the social realist style. He could not ignore the hypocrisy of the American army fighting a racist enemy during the Second World War, while at the same time enforcing racial segregation of its own troops.

Lewis came to the conclusion that merely mirroring social conditions was not an effective agent of change, saying: “I used to paint Negroes being dispossessed; discrimination, and slowly I became aware of the fact that this didn’t move anybody, it didn’t make things better.” Instead, he decided to devote his life to exploring more universal aesthetic concerns through abstraction, colours, forms and textures.

“The goal of the artist must be aesthetic development, and in a universal sense, to make in his own way some contribution to culture.” – Norman Lewis

Norman Lewis and Abstract Expressionism

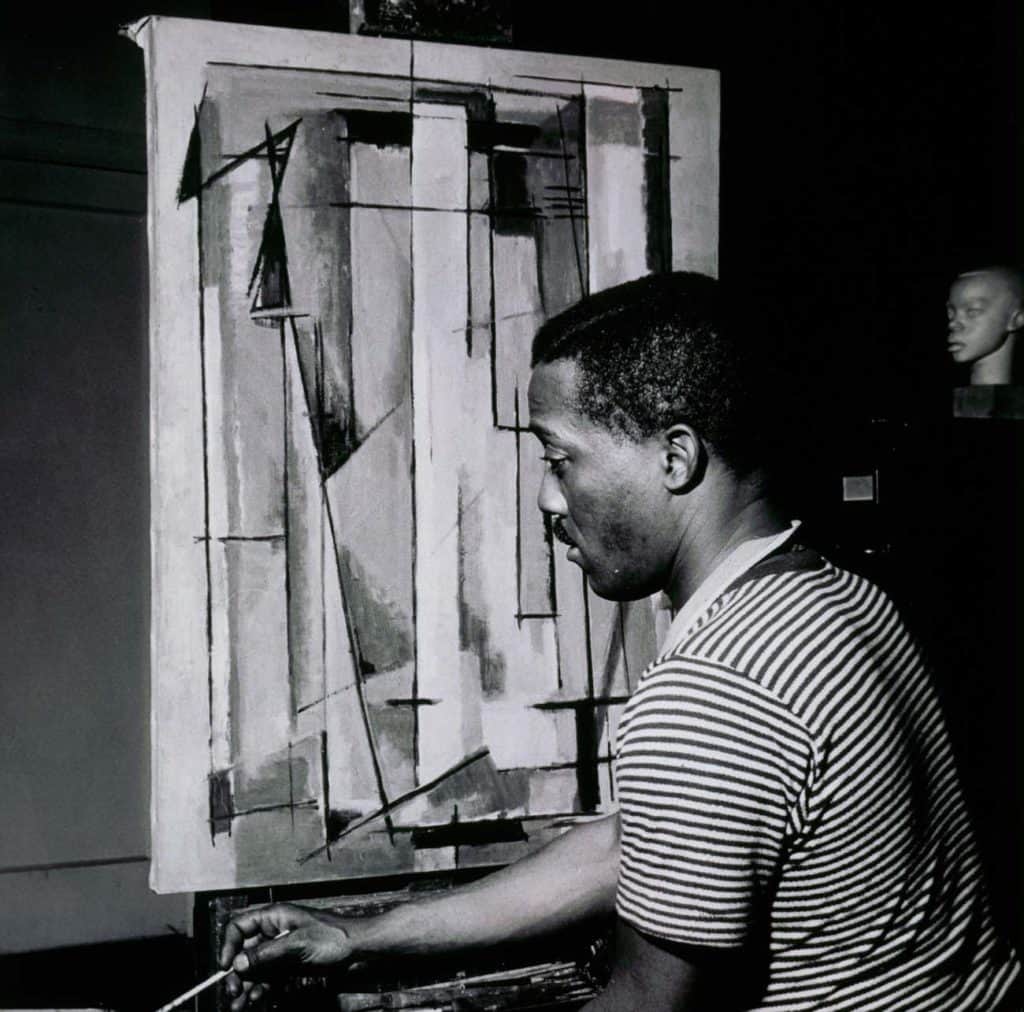

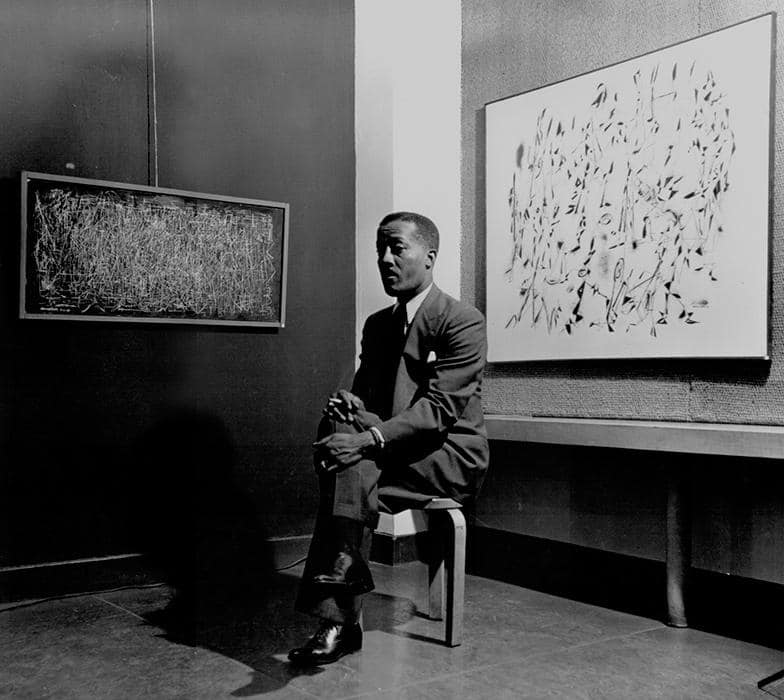

It was around 1946 that Lewis started to explore a gestural approach to abstraction, soon establishing himself as the only African American artist among the first generation of Abstract Expressionists. He was represented by the Willard Gallery.

Lewis found inspiration in a variety of sources, ranging from music and nature to Chinese, Japanese and African art, and the art of Wassily Kandinsky and Mark Tobey. He allowed himself to experiment freely with different approaches to abstraction. One of the most distinctive aspects of Lewis’s abstract style is his use of the oftentimes calligraphic line. His brushstrokes, lyrical and energetic, possess an architectonic structure giving them real power. The lines create abstract forms on the canvas, dividing the space into appealing particles of abstraction. In “Crossing” (1948), the canvas is outlined with horizontal lines, while the entire middle part is made up of vertical lines and shapes. This makes the central part jump out distinctively at the viewer, even more so due to the use of more vibrant colours in the middle section.

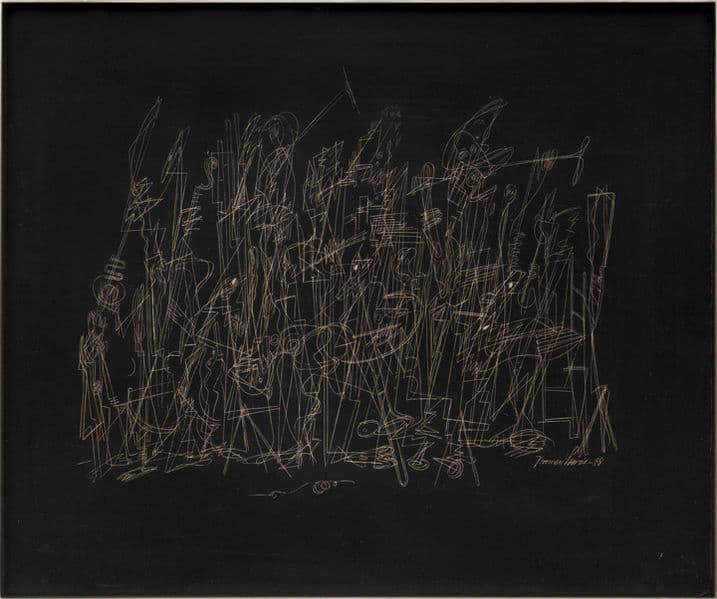

Lewis also became known for his extensive use of black in his paintings. In “Jazz Band” (1948), for example, Lewis made incisions on black coated masonite board, the thin white lines creating an abstract explosion of a jazz band, where only a few instruments remain vaguely recognisable.

The Spiral Group

In 1963, Norman Lewis, Romare Bearden, Hale Woodruff, Charles Alston, James Yeargans, Felrath Hines, Richard Mayhew and William Pritchard formed a collective known as “The Spiral Group.” The aim of the group was to promote aesthetic mastery and cultural universalities. They wanted an approach to art that was not only universal, but unifying. The artists in the group met regularly to discuss whether or not, and in what way, the realistic depiction of racial inequality in art helped black culture. They also studied how excellence in the realm of aesthetics might increase the influence of black artists in America.

Norman Lewis: The Last Two Decades

During approximately the last two decades of Lewis’s life and career, he started once again to engage with figuration, but this time, he created his very own unique blending of abstraction and figuration. His rhythmic lines and shapes now hinted at figures moving through his layers of colours.

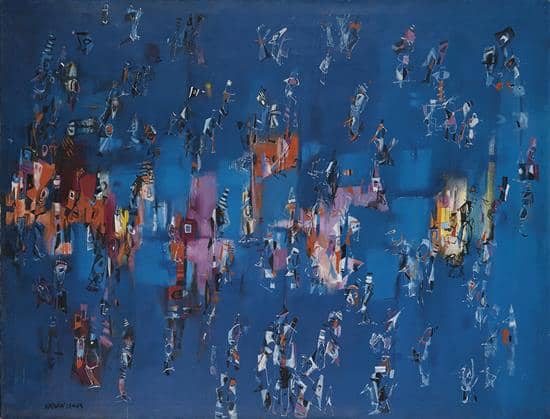

“Untitled” (ca. 1957) shows Lewis’s transition from pure abstraction towards this new approach, that blends abstraction with figuration. Little sharp modernist figures and shapes are scattered all across a blue background. Even as early as 1953, in “Migrating Birds”, we can see Lewis’s evolving work with figures and abstraction, as a large flock of white birds, consisting of little splatters of paint, criss-crosses the canvas.

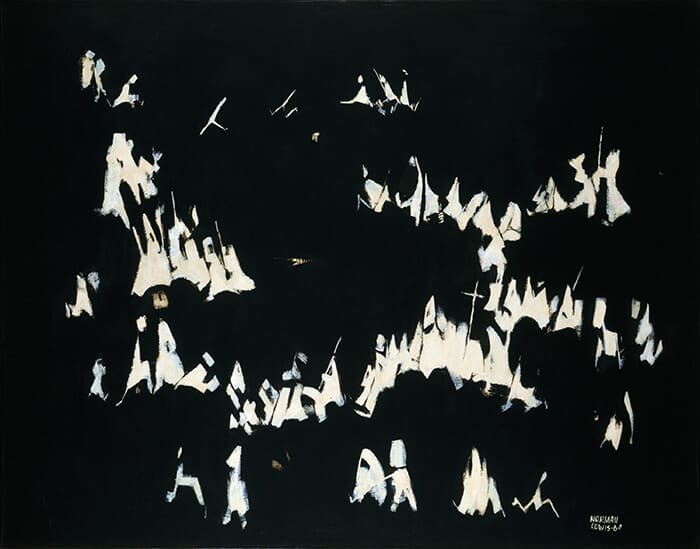

Lewis made several paintings inspired by the Ku Klux Klan, which alluded to the dark, clandestine activities of the group. One of these is “America the Beautiful” from 1960, which shows white hooded figures against a black backdrop. He continued to explore issues surrounding the Civil Rights Movement in the ‘60s and ‘70s in a group of black-and-white paintings evolving from his Ku Klux Klan works.

In these last decades, it seems that Lewis found an equilibrium between his concerns with social justice and a more figurative human element, and his pursuit of abstraction and the realm of aesthetics in his art.

Rediscovery and Recognition

In 2015, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts put on the exhibition “Procession: The Art of Norman Lewis”. At the time, not many people knew about Lewis. He had fallen into oblivion after the peak of Abstract Expressionism. Even back then, he never achieved great fame or financial success like his fellow artists Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, or Willem de Kooning, with whom he frequently exhibited. Lewis, like other African American abstract artists, had struggled in his in-between position in the art world. While the white, post-war, American art establishment mostly dismissed the work of black artists, African American art dealers and collectors were generally dismissive of abstract art, as they believed that social justice could only be achieved by art that directly depicted social issues. Lewis was also never mentioned in any of the important historical narratives about Abstract Expressionism of the time, and is missing from iconic photographs of the period of Abstract Expressionism, giving the false impression that there were only white Abstract Expressionists. The fact that he was not as widely recognised as his peers meant that Lewis also had to work extra hard to make a living: he took on jobs teaching art at the Augusta Savage House and Studio and the Harlem Community Art Center, and also worked as a taxi driver to support himself.

Yet Lewis did gain a certain degree of national recognition by the late ‘50s, following several well-received solo exhibitions at the Willard Gallery. He was included in the 1951 MoMA show Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America, and in 1955, his painting “Migrating Birds” (1953) won the Popular Prize at the Carnegie International Exhibition – he was the first African American to ever win that award. In 1956, Lewis was selected to represent the United States in American Artists Paint the City, an exhibition showing works by 36 different American artists in the American Pavilion at the 28th Venice Biennale. He and Jacob Lawrence were the only African American artists included in the show. His 1950 painting “Cathedral”, a structured black and red work, was exhibited.

Representation and Museum Collections

Today, Norman Lewis is represented by Swann Galleries and Michael Rosenfeld Gallery. His works are held in major museum collections, including the Museum of Modern Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, Smithsonian American Art Museum, and Museum of Fine Art, Boston. Lewis will be featured in the upcoming Phillips Collection exhibition “Riffs and Relations. African American Artists and the European Modernist Tradition” in Washington D.C. (29 February – 24 May 2020).

Relevant sources to learn more

Read more about the life and art of Norman Lewis here:

IdeelArt: Norman Lewis, a Neglected Gem of Abstract Expressionism

To discover the work of other pioneering African American abstract artists, read:

Lost (and Found) Artist Series: Alma Thomas

Lost (and Found) Artist Series: McArthur Binion

Lost (and Found) Artist Series: Howardena Pindell

Norman Lewis was the only African American artist among the first generation of Abstract Expressionists.

Where did Norman Lewis live?

Norman Lewis was born in Harlem, New York, and lived and worked in New York all his life.

What style was Norman Lewis known for?

Norman Lewis was known for his intricate line-work, structured forms, and use of black. During the last part of his career, he merged figurative with abstract painting.