Articles and Features

Lost (and Found) Artist Series: Samia Halaby

By Shira Wolfe

“I always wanted to be an abstract painter, that was in my heart always.” – Samia Halaby

Artland’s Lost (and Found) Artist Series focuses on artists who were originally omitted from the mainstream art canon or largely invisible for most of their careers. This week, Samia Halaby takes centre stage. The Palestinian artist has been living and working in New York since the 1970s, developing a bold language of abstraction and pioneering computer-based kinetic art in the 1980s. With a prolific career mostly spent under the radar, today Halaby’s work is part of prestigious institutions around the world.

From Jerusalem to the United States: First Abstractions

Samia Halaby was born in Jerusalem in 1936, where she received a warm upbringing and remembers being told countless stories about the city and surroundings by her grandmother. In 1948, when the State of Israel was declared and her home was looted and occupied, her family was displaced to Lebanon. After some time, her father moved the family to the United States. Interviewed by Artland, Halaby describes her intuitive move towards art from an early age: “It was a love of making things that became focused through gentle remarks by my mother,” says Halaby.

Having always wanted to be an abstract painter, Halaby cites two periods in the history of art that profoundly affected her practice. The first was Arab abstraction, found in the symmetry and geometric forms in the panels of the great mosques she visited, in particular the Dome of the Rock and Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, and the Great Mosque of Damascus. The second period was twentieth-century abstraction, starting with Impressionism, and followed by Modernism. Halaby was influenced by Cubism, Constructivism and Suprematism, as well as Abstract Expressionism in the United States. Abstract art always had an electrifying and profoundly moving effect on her.

“Whenever I’ve had an opportunity to go to a museum and see one of these exhibitions, especially the Soviet artists, I feel an urgency, I feel like I have to run out immediately, I can hardly contain myself to see the entire show, I want to join a demonstration, I want to go to my studio and get all the colours out and make more paintings,” she explains in a Guggenheim artist talk from 2019. Halaby considers abstract art not as belonging to the past but an expression of working-class culture, which will continue to be reinvented.

Finding her Own Language of Abstraction

Halaby received her MFA at Indiana University. During her final student days she was especially inspired by the works of Paul Klee and created a series of semi-abstracted, colourful shapes. After graduation in 1963, she travelled throughout Italy and spent hours visiting museums, finding herself especially affected by Da Vinci’s The Last Supper.

In the years following her graduation, while teaching at the Kansas City Art Institute, Halaby felt a strong need to remove the academic influences from her artistic practice and decided to try to start at the very beginning, asking herself what she sees when she looks at the world, in order to come to her own language of abstraction. She began to construct a series of still-lifes, in which she examined how the three-dimensional object can be portrayed on a two-dimensional surface. She worked on these geometric still-lifes from 1966-1970, exploring architectural planes and lighting.

A 1966 trip to Jerusalem, Damascus and Istanbul was deeply influential, as Halaby visited many mosques and soaked up all the incredible Arabic geometric abstraction in the architecture, at the time falsely described by art historians merely as decoration. The abstraction that Halaby discovered in the panels of the mosques would become a permanent part of her formal practice.

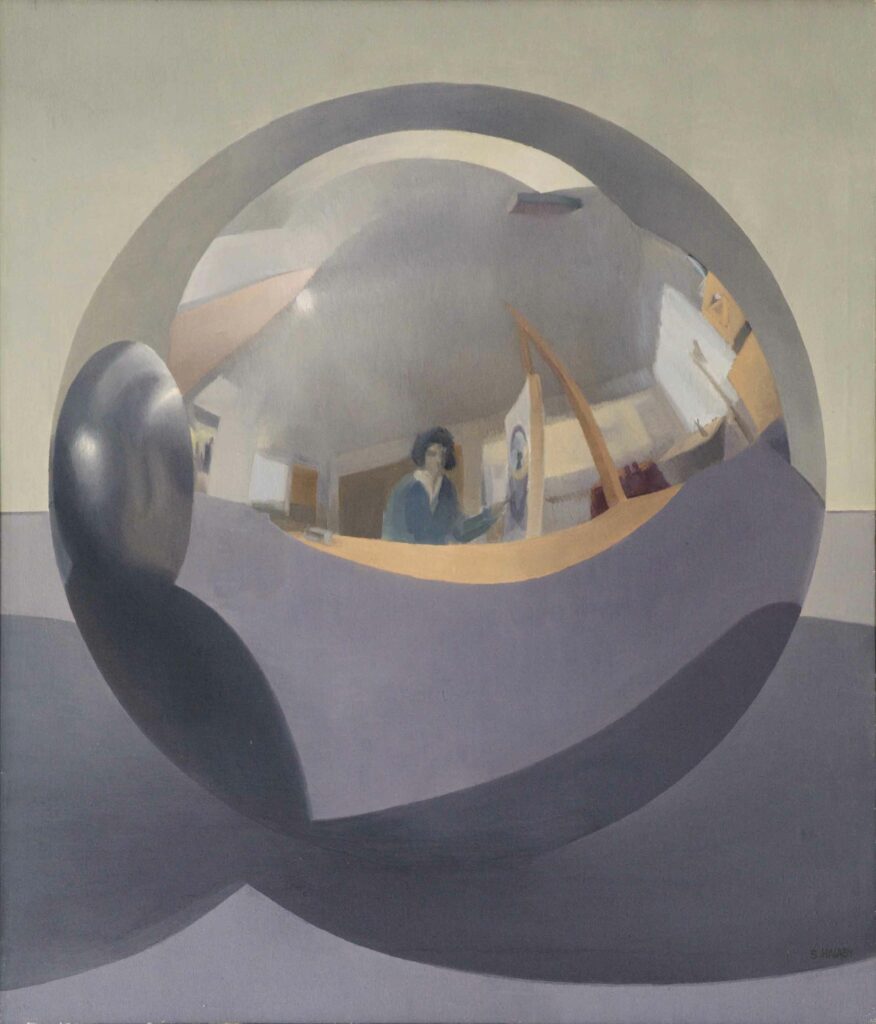

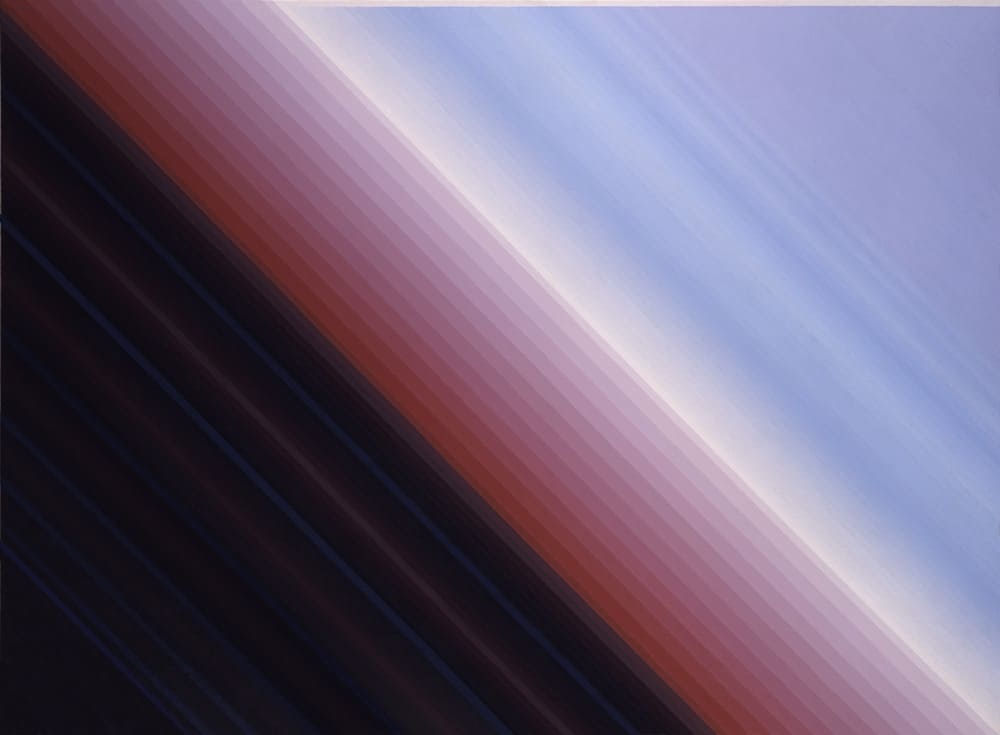

Wishing to push further into the examination of life outside the self, Halaby purchased several books on geometry, which led to her series Helixes and Cycloids (1971-1975). She drew parallels between the symmetry and rhythm of geometry and the beautiful mosque panels she had been studying. She also developed a fascination for metals, and began exploring these in painting – her Self Portrait from 1972, for example, is made up entirely of metal helical forms. The artist explored the contradictions of how we see since our perception is not actually three-dimensional. By eliminating depth-cues, the paintings in her Diagonal Flight series (1974-1979) started turning into horizon lines, moving beyond the three-dimensional illusion. These paintings are like moments captured in mid-flight.

Beirut, the Dome of the Rock, and New Inspiration

In 1979, Halaby visited Beirut and befriended the sculptor Mona Saudi. This trip was important as she had been experiencing a dry spell in her painting and was searching for new directions. Saudi included Halaby in the many exhibitions she was organising as director of the Plastic Arts Section of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation. A pivotal moment in her career was an exhibition that was organised through Saudi at the Kunstnernes Hus in Oslo, where specific interest was shown in art created by artists who had experienced life under oppression, under attack, and during revolution.

She also returned once more to the Dome of the Rock mosque, remembering a specific panel on the outside of the mosque, which inspired her to use the rectangle and create all other shapes within it. In her paintings from the early ‘80s, she explored the possibilities of the rectangle and added textures inspired by the marble inlays of the mosque.

The 1980s were a fertile period for Halaby, during which she felt she had finally freed herself of academia and was working in a totally abstract manner in her own style. During this period, she allowed herself a lot of time to work on her paintings – nobody was buying her works anyway, she explains, so she could enjoy working slowly on the paintings, sometimes taking up to 10 years to finish a work. In her Autumn Leaves and City Blocks series from 1982-1983, Halaby abandoned the brush and used a palette knife for the first time. Seeking to show the beauty of autumn leaves, she realised she would have to let her paintings imitate the growth and decay of these leaves, capturing their natural life cycle through abstraction.

The artist continued to emulate natural processes in a series of works from 1984-1992 titled Growing Shapes and Centers of Energy. She allowed her compositions to develop intuitively, deepening her study of the line, path, shape, and motion. More and more freedom started to appear in her brushstrokes and shapes – she allowed herself to explore shapes other than the rectangle and attained a greater sense of freedom in her intuitive compositions.

“I came to the computer because of what its nature is, what it can do. The nature of programming, the possibility of motion and sound and time. To me, it was a technology of our time, and if I were a painter of my time, I have to use a technology of my time.” – Samia Halaby

Computer-Based Kinetic Art, 1983-1995

Halaby is truly an artist of her time, who faces each new development with curiosity and excitement. In an interview with The Guru Meditation, Halaby elaborates on her pioneering artistic work with computers in the ‘80s. In her words: “I came to the computer because of what its nature is, what it can do. The nature of programming, the possibility of motion and sound and time. To me, it was a technology of our time, and if I were a painter of my time, I have to use a technology of my time”. In 1986, She purchased an Amiga 1986 and began teaching herself computer programming in order to independently discover the nature of this new technology.

“I did not want anyone else, certainly not programs, to decide any of the aesthetic forms that I would use,” explains Halaby. “I determined not to use software but only programming languages. I taught myself how to program and found that in programming I could create paintings that not only moved and grew and changed but also made sounds. To me this was a more complete imitation of the world we live in than just still images. In the process, I fell in love with programming and grew to think of it as something very beautiful, itself a reflection of the motion of human life.”

She speaks of accomplishing this goal as extremely exciting, but also notes the difficulty of getting these ideas out into the world, and the barriers created by competing corporations. After sufficiently satisfying her curious nature and having developed this part of her artistic language to the extent that she wanted to, Halaby eventually returned again to canvas and brush.

Painterly Abstraction and Hanging Sculptures

Halaby’s paintings from the 1990s to 2000 were characterised by a continuing move away from the use of obvious geometric forms such as squares, rectangles and triangles. Intent on reinventing herself again, she started making paintings with small brushstrokes, submerging herelf in “painterly abstraction” influences by artists like Monet and Seurat. Spontaneous brushstrokes and colour dominate these canvases, inspired by how the eye keeps shifting focus and wandering around its surroundings.

In 2000, Halaby started creating works free of the stretcher, which she called “hanging sculptures”. She began working on these following a project with Palestinian artist Vera Tamari and students at Birzeit University in Ramallah. Developing a system of cutting and stitching pieces of canvas, she created borderless, hanging compositions. For Halaby, these pieces conform to similar principles as sea life on a reef, able to grow in a universal direction unaffected by gravity. In this body of works, Halaby finds her own language and expression within the vast tradition of collage art. A particularly moving piece is Palestine from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea (2003) which shows the different types of vegetation and surroundings in Palestine in the form of a hanging sculpture.

Drawing the Kafr Qassem Massacre

In 2017, Halaby undertook a special labour of love for Palestine and the determination that Palestinian history will not be erased, in the shape of her book Drawing the Kafr Qasem Massacre. The Kafr Qasem Massacre was carried out in 1956 by the Israeli Border Police, under the cover of the tripartite attack on Egypt by England, France, and Israel. Forty-nine Palestinian civilians were killed on their way home from work during a curfew of which they were unaware. Speaking about this project, for which Halaby made a series of realistic documentary drawings depicting the Kafr Qassem Massacre, she explains: “I was led to it by a daughter of Kafr Qasem sometime during the mid-1990s. Her name was Aishe Amer and she was determined that every Palestinian artist should do at least one painting about the massacre. She took me there and hosted, introduced, and guided me and would not let go until she connected me to her friends there. As time went by, the compelling power of the story led me to create far more than one painting on the subject. I determined that the drawings would not be an exploration of painting but a performance of my knowledge and skill in the service of documentation.”

New Works

Halaby’s passion for and exploration of abstraction continues as an unstoppable and inspiring force. She loves how different people can find surprising connections to each other through an abstract work of art. According to Halaby, each person carries a storehouse of visual experience from their lives, and something from this visual storage might suddenly be recognised in the abstract painting. “If you like it and you feel there is something that catches you in it, that means you and I have made a communication, the painting has become a channel between the two of us,” explains Halaby.

More recent works that are important to Halaby include Jerusalem, My Home (2014) and New York Avenues and Japanese Clouds (2018). While working on Jerusalem, My Home, Halaby returned to her birthplace, and to that which represents Jerusalem the most to her, the Dome of the Rock. She represented it as a half-sphere, and applied the Arabic abstraction in the abstract panels and geometric forms, the very abstraction that she first discovered in the Dome of the Rock. New York Avenues and Japanese Clouds is Halaby’s experience of New York’s dark city blocks and luminous avenues, coupled with a birds-eye view approach through the clouds, as commonly found in Japanese art.

When asked what is next, Halaby replies: “I have an ambition: to paint a luminous airy space without shape or imagery. On that path, I am committing myself to use less geometric forms than in the past, and to allow lines inspired by both script and branches to be the basis of a process of growth through repeated overlapping variation.”

How Samia Halaby Defies the Inequalities of the Art World

As a female immigrant in the United States who was entering the art world in the 1960s, Halaby didn’t have it easy. She explains how all the doors in New York were closed to her: “Only a few doors were open to me, and mostly in the Midwest in small flirtations with museums. I used to brag that I have more museum credits but no New York gallery ones.” However, she has continued to live and work tirelessly in New York since the 1970s, while exhibiting at various alternative and artist-run galleries, and eventually made a name for herself in the Arab art world, leading her more and more to the extended international scene. In her words: “I had to jump over New York to reach the Arab world market and from there through auction begin peeking into the international arena.” Halaby’s works are now collected by many museums around the world, including the Guggenheim in New York and Abu Dhabi, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Institut du Monde Arabe, and Birzeit University. She is represented by Ayyam Gallery (Beirut and Dubai).

Relevant sources to learn more

Samia Halaby website

Ayyam Gallery

Palestine Museum Woodbridge

Guggenheim Museum Artist Talk

For previous editions of our Lost (and Found) Artist Series, see:

Etel Adnan

Ming Smith

Alma Thomas