Interviews

The Shape Of Color: Robert Zandvliet on Color, Technique and Letting Go

By Adam Hencz

“Painting is the perfect way to learn about life, because the act of painting demands questions.”

Robert Zandvliet

An average person is exposed to over ten thousand images a day – an overwhelming noise of instantly dissolving ads, posts, snapshots, videos, and brand messages with ephemeral and superficial content. What if we rather paid attention to the essence of what surrounds us? What could we see then? What can a painter tenaciously working on a life-long quest for the truth in painting see?

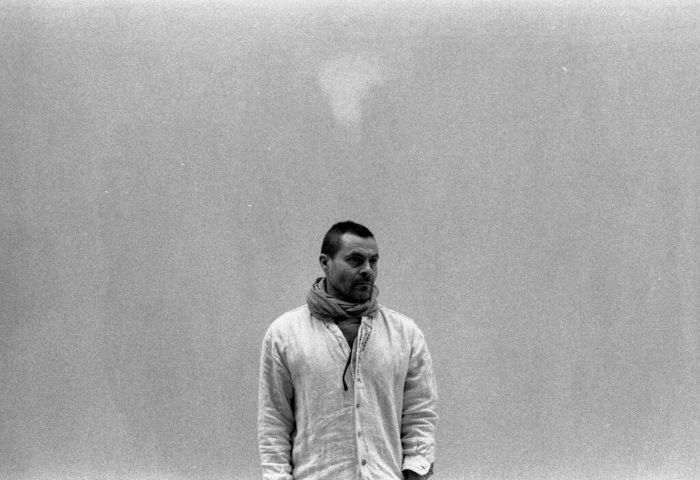

One of the foremost Dutch painters working today, Robert Zanvliet finds inspiration in the act of observation and diligent research, an extensive process of trials and errors before absorbing the ability to unveil archetypes of his subject matter. Self-reflection, the balance of control, and the unknown feed into the cyclical shifts of Zanvliet’s focus that ranges from commonplace motifs like an airplane window or a camera lens, through abstracted landscapes that reorient the viewer’s perception, to producing painterly studies of color and form.

For his most recent body of work titled Le Corps de la Couleur, Zandvliet uses the tradition of painting as a guiding thread to explore different approaches to a color’s physical shape. Four large-scale works of the series will be shown at Bernhard Knaus Fine Art in Frankfurt on the occasion of the third solo exhibition of the artist in the gallery space, opening on the 19th of February, 2022. Part of the show will consist of smaller paintings from the workgroup Le Jardin, a metaphorical body of work revolving around elemental themes like nature, constitution, and interpretation. Even though the interview format is confined within limits when it comes to grasping the essence of the works themselves, in our conversation with Robert Zandvliet, we made an attempt to unravel the pure intentions of the painterly practice.

Robert Zandvliet lives and works in Haarlem, Netherlands, and has been awarded international art prizes and his works are part of the collection of the Stedelijk Museum, among others.

I would like to thank you Robert for sparing your time with me to have a conversation about your work. Where are you at the moment, where are you calling from?

I am in my studio in Haarlem, a city very close to Amsterdam. It is a large studio and I am surrounded by several paintings, most of them unfinished. I have both large paintings around me along with some smaller ones, a few of which will go to the Le Corps de la Couleur exhibition at Bernhard Knaus Fine Art in Frankfurt.

Recently you have been creating paintings that are studies of color and your upcoming show in Frankfurt seems to be a delicate continuation of this investigation. Can you tell us a bit about the works you will display for the Le Corps de la Couleur exhibition? How does the show fit into your oeuvre?

Le Corps de la Couleur translates in English simply as ‘The Body of Color’. It is a research I started about four years ago. Every time I am working on a series, after a few years I would make an update on what I had been doing and aim to find a new theme or a new interest in my practice. After painting with dark tones of blue and brown and making dark works, I thought it was time to make more colorful and fresh pieces. I came to the realization that even though I had been painting for more than twenty years, I want to discover color on a deeper level and learn what different colors mean to me. I did not want to make abstract paintings like monochrome paintings about colors. I did not want to make paintings about how colors react to each other either. I was more interested in the content of each color itself because when I see color in the outside world, it is always attached to something. Color itself does not exist alone. So I thought that if I wanted to get closer to the essence of a color, then first I had to figure out what form or body that specific color belongs to. I decided that every painting will depict just one color, and every painting was called after that color. Of course this process reflects my own personal experience and it also has to do with history, the works I made before, and the way I relate to my surroundings. It is not a scientific approach or has anything to do with color theories – it is my own experience.

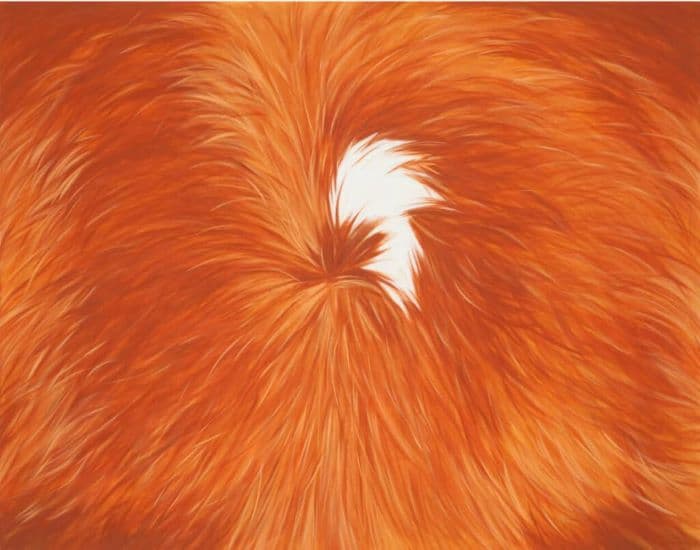

The four paintings which I will show in Frankfurt will be Abendrot, the investigation of the red color. Then a painting called IJs, discovering more whitish and bluish hues. The title of the third painting called Vos means ‘chestnut color’ but also ‘fox’ in Dutch. The fourth painting is called Git, which is a black painting of a black mineral that also connects with an earlier series that I made called Seven Stones. One is a stone, the other one is a landscape and there is a part of an animal and then an object, a curtain. I like that there are different kinds of themes in the series and that it is not only about nature, humans, or stones. I find that these differences give another layer to the series. Every painting has its own story, every painting has a different approach and subject. It can be a tree, it can be a train, a curtain, an ice landscape, or the Moon – all depending on the color and on how the color comes to me. It is quite a long process, and it takes a while to figure out and make decisions about which image fits best to a color.

Do you also use different techniques to create these paintings?

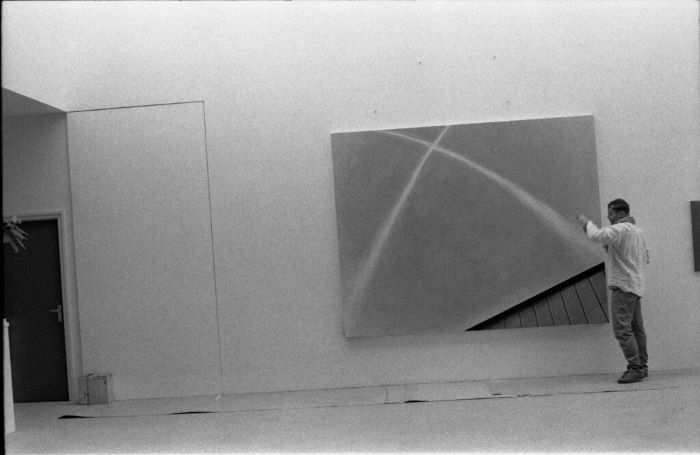

If I am creating a stone painting, I paint on a very rough and raw, unprepared linen, because its tactility resonates with the stone and is unpolished. I painted Git with a paint roller, using black, blueish, and greenish acrylic paint which I make myself with a lot of pigments. I only put the roller into the paint for half, so that when I roll it over the canvas, it will reveal the structure of how it is painted. If you compare that with Vos, there you see a layer of hair and fur which I painted with the tip of a brush – very thin lines in a sort of round curve. This is a completely different language than the stone painting. For IJs, I used a combination of spray and oil paint because with the latter you can achieve a kind of reflection of the light the snow or ice has. Every subject asks for another approach and I want to follow the demands of the color.

What kind of experiences lead you to conceive an idea for a specific color and image?

I started the series with the green painting. Green instantly means nature to me. I just look out from my studio and I see my neighbor’s lawn, a green field of grasses, a perfect color field, the perfect image for the first painting. But I started asking questions like ‘Do I need a horizon?’ or ‘How shall I paint the grass?’ – since I did not want to make a realistic painting. I had to read about it and try things. Slowly, I got a grip on the image since there are so many shades of green in that view. The root of grass is more whitish, and when the grass is growing in the direction of light, it gets darker and darker. This awareness and the fact that I am conscious about that is changing the image of the painting. About the yellow painting I made – I realized that yellow, as a color, is always on the move. If you try to paint a yellow square, it always wants to leave the form and the canvas. It just does not like borders. For yellow, I painted a moving train that is only shown from the side, without the rails or the sky above, but only yellow lines and a gray blur which depicts the windows.

What kind of habits or rituals do you have when you paint? What does a day at your studio look like?

I never work on the weekends, I only work from Monday to Friday. I enter my studio in the morning and I spend some time drinking coffee, reading books and after two hours I start painting but before that, I already start looking around and thinking about what I should do. I make a plan for the day and start to make my own paint. I use egg paint, egg tempera, which I make myself, using the yolk of the egg, combined with a little bit of oil and then I add pigments to it. This is a sort of habit which I have to do every day. Then I make a color that I think I need, and then I try how it works on one of the smaller paintings. When I find the right color, I use it on a larger painting as well but sometimes it just isn’t the right color. I have one room with a big table with all the small works on paper. I am always working on twenty, maybe thirty small works at a time. I use the paint which is left for these landscape paintings, which I never make a plan for. Then I come back to work on large paintings – looking at them and making decisions about for example the background.

The artist is often considered both a creator and a destroyer. How can you describe the role of destruction in your practice?

I always follow a plan, especially when working on large paintings. For Le Corps de la Couleur it just took a while to find the right bodies for each color. I made four different versions of the IJs painting to find the right image. One was too figurative and it just wasn’t loose enough. I had to destroy it and put another canvas on. Then I had to make new sketches again to continue searching. Even though the first and the second paintings were good paintings, they were too much about being a landscape and about the image itself and not so much about the color anymore. So in those terms, they were just not good enough, so I destroyed them. This happens very often. The large paintings I usually have to paint two or three times.

“People look at the price and not at the content of the work. Art is a status symbol these days.”

Robert Zandvliet

How do you incorporate sketching and drawing into your practice?

Drawing to me is about figuring out possibilities. I don’t make perfect drawings, just sketches to figure out what the consequences of the choices I make could be, and also to see how an idea would work in a composition. I ask questions like ‘What are the consequences of painting an object with an empty background?’, ‘Is there another world behind the object?’, ‘What do I have to do with the borders?’ or ‘How will I use my brush?’ – all these questions I can answer with the help of making sketches. When I sketch, fewer and fewer options stay available, and then at the end, there is only one option, which I will use on a larger painting. Sketching means that I will more or less know how I will make a painting. I like the idea that a painting has fresh energy in it. Like it has been done just once and painted for the first time. When a painting is a perfectly worked out plan, it is boring, but when it is only roughly sketched it is not strong enough. For me sketching is following a path of possibilities and in the end, I will know the route to follow.

How does your relationship with a painting change, once it is completed and leaves your studio?

Painting is the perfect way to learn about life because the act of painting demands questions. I have to keep on looking, researching, and discovering things. While I am working on a painting, I am also getting closer and closer to the essence of the work – a process that can take even three months or half a year from the first time the idea for the painting is conceived in my head. When I am slowly getting close to the core, I really feel that on one hand I am in control but on the other hand – in the case of the color paintings – the color is leading me to the right places. This is a marvelous feeling. I believe that this energy moves into the painting while I am working on it. But when it is finished, I get to the end of the path and it is over. The work is only valuable to me because I had the experience of making it. But after that, I just let it go. An Aboriginal artist once said that he could not imagine that we in the West have museums, to store our paintings and art pieces. To him, a museum is a graveyard, since after the act and experience of painting is over, the artwork itself is gone as well. An art piece alone does not mean anything to him after that.

What is your take on the tremendous amount of images we are surrounded by in our daily lives?

I am making images myself therefore I am also part of it. But I still believe that as an artist, I load an image with spiritual energy. This is where I can make a difference. I really believe that people see the energy of the act in the image when an artist is truly connected to their work. For example, I have this strange experience every time people come to my studio – they always like the last painting I have just been working on the best. In a good painting, there is energy that stays behind, and I believe that people can see this. Why are some paintings really really good? Why do some of the art pieces keep on having this kind of energy? This is a big mystery of course, and I also want to know the answers. During work, sometimes I feel that ‘now I understand a little bit.’ But once I have this feeling, it is leaving me immediately. A good piece makes people aware, it makes people question their surroundings. It can only happen when a piece has this kind of energy. Otherwise it is just an image, just a photograph or a snapshot that is immediately leaving your mind.

What is your opinion on the materialism of today’s world? What do you think of art that is completely commercialized?

I wish I could change it but we just have to live with it. It worries me sometimes because people cannot see the content anymore. That is my concern. People look at the price and not at the content of the work. Art is also a status symbol these days. People can now afford to buy expensive art. When you go to art fairs, there are plenty of shiny art pieces these days. Mirrors and flashy paintings that people can reflect in. But it is quite complicated and I don’t want to complain too much. I am just staying true to my content and want to make good paintings.

What is your current focus or a body of work that you are working on?

Every four or five years I am changing my theme and field of interest. The Bernhard Knaus Fine Art exhibition will have four paintings from Le Corps De La Couleur, but also includes the starting point of a new theme I am at the beginning of researching. The series is called Le Jardin. I use the garden as an example of nature, because to me the grasses, trees, and plants, and the way they grow, form interesting overlapping structures. The starting point was the green painting of Le Corps De La Couleur, but the investigation is starting to be more and more complex. I am now trying to figure out how I can form different structures into a more complicated composition. I start with looking at reality and bringing back more universal and painterly solutions. Eventually, it will become a series which I will call Paradaidha, an old Persian word for paradise, that also refers to a garden enclosed by high walls. For me, a painting is also a sort of garden surrounded by a wall, so the title works as a metaphor as well. At the moment I keep it small to allow people to understand my view of nature and the structures behind it.

Relevant sources to learn more

Explore a unique selection of works by Robert Zandvliet available for sale on Artland

Read the latest interviews on the Artland Magazine:

Artland Interviews: Jwan Yosef

Interview With Artists and Creative Technologists Tin&Ed

Stolen Stories: Interview with Ghanaian Artist Kojo Marfo

Wondering where to start?